THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

1

1

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

`

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND

MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES—BACKGROUND PAPER

Approved By

Jan Brockmeijer

This paper was prepared by a staff team led by Erlend Nier,

comprising Heedon Kang, Tommaso Mancini, Heiko Hesse (all

MCM), Francesco Columba (WHD), Robert Tchaidze (EUR), and

Jerome Vandenbussche (EUR).

CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION ________________________________________________________________________________ 3

II. INTERACTIONS BETWEEN MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICY ________________ 5

A. Policy Interactions––Conceptual Framework ____________________________________________________ 5

B. Monetary Policy and Side Effects on Financial Stability _________________________________________ 6

C. Macroprudential Transmission and Effects on Real Economic Outcomes _____________________ 11

III. EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS _______________________________________________________________________ 16

A. Macroprudential Policies—Effects on Credit, House Prices, and Output ______________________ 16

B. Effects of Macroprudential Policy Measures—Symmetric or Asymmetric? _______________________ 24

IV. COUNTRY CASES ____________________________________________________________________________ 28

A. Selected Central, Eastern, and South-Eastern Europe Countries ______________________________ 28

B. Brazil __________________________________________________________________________________________ 33

C. Turkey _________________________________________________________________________________________ 38

D. Korea __________________________________________________________________________________________ 44

E. United States __________________________________________________________________________________ 51

REFERENCES _____________________________________________________________________________________ 60

BOX

1. Case Studies on Monetary and Macroprudential Policies _______________________________________ 4

FIGURES

1. Number of Macroprudential Measures—Tightening or Loosening ____________________________ 25

2. Selected CESEE Countries: Foreign Currency Loans and Policy Interest Rate Spreads, 2005–11 ___ 29

3. Brazil: Macroeconomic Conjuncture and Policy Responses ____________________________________ 33

December 27, 2012

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

2

2

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

4. Brazil: Credit Expansion ________________________________________________________________________ 34

5. Brazil: Impacts of RRs Tightening (1 percent) on Credit Growth _______________________________ 36

6. Brazil: Effectiveness of Changes of Capital Requirements on Consumer Loan _________________ 36

7. Brazil: Monetary and Macroprudential Policy Coordination ___________________________________ 37

8. Turkey: Credit Growth and Current Account Deficit ___________________________________________ 39

9. Turkey: Interest Rates, Reserve Requirement Ratios, and Growth of Lending _________________ 42

10. Turkey: Inflation Expectations and Inflation Rates ____________________________________________ 43

11. Turkey: Cumulative Liquidity Injections ______________________________________________________ 44

12. Korea: House Prices and Household Debts ___________________________________________________ 45

13. Korea: Monetary Policy as a Countercyclical Tool ____________________________________________ 46

14. Korea: Effectiveness of Limits on LTV and DTI Ratios _________________________________________ 47

15. Korea: External Net Assets of Banking Sector ________________________________________________ 49

16. Korea: Foreign Exchange Rates and CDS Premium ___________________________________________ 50

17. United States: Interest Rates _________________________________________________________________ 52

18. United States: Inflation Rates and GDP Growth Rates ________________________________________ 52

19. United States: Recommended Policy Rates from Baseline Taylor Rule Responding to CPI

Inflation and A Variant Responding to the GDP Deflator ____________________________________ 54

20. United States: Recommended Policy Rates from Baseline Taylor Rule Responding to CPI

Inflation and A Variant Responding To Core PCE Inflation ___________________________________ 54

21. United States: Leverage Ratio ________________________________________________________________ 56

22. United States: Net Federal Funds and Security Repo Funding to Banks and Brokers-

Dealers _______________________________________________________________________________________ 57

23. United States: Standard and Poor Composite Home Price Index _____________________________ 58

TABLES

1. Monetary Policy Effects on Financial Stability ___________________________________________________ 7

2. Use of Macroprudential Measures Across Countries __________________________________________ 19

3. Effects of Macroprudential Measures on Credit Growth _______________________________________ 20

4. Effects of Macroprudential Measures on House Price Appreciation ___________________________ 21

5. Effects of Macroprudential Measures on Output Growth and Residential Investment ________ 22

6. Effects of Macroprudential Measures on Capital Inflows ______________________________________ 24

7. Number of Macroprudential Measures—Tightening or Loosening ____________________________ 24

8. Effects of Macroprudential Policy Stance on Credit Growth ___________________________________ 26

9. Effects of Macroprudential Policy Stance on House Price Appreciation _______________________ 27

10. Selected CESEE Countries: Inflation Target, Inflation Outturn, and Policy Rates, 2006–11 ____ 28

11. Selected CESEE Countries: Use of Macroprudential Instruments Addressing Foreign Currency

Loans, 2002Q1–2012Q1 ______________________________________________________________________ 31

12. Selected CESSE Countries: Determinants of the Share of Foreign Currency Loans, 2001Q1-

2012Q1 ______________________________________________________________________________________ 32

13. Brazil: Changes of Capital Requirements on Consumer Loans _______________________________ 35

14. Turkey: Macroprudential Measures Undertaken in 2008–11 _________________________________ 41

15. Korea: Changes of Limits on LTV and DTI Ratios _____________________________________________ 48

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

3

3

I. INTRODUCTION

1. This paper provides background material to support the Board paper on the

interaction of monetary and macroprudential policies. It analyzes the scope for and evidence on

interactions between monetary and macroprudential policies. It first reviews a recent conceptual

literature on interactive effects that arise when both macroprudential and monetary policy are

employed. It goes on to explore the “side effects” of monetary policy on financial stability and their

implications for macroprudential policy. It finally addresses the strength of possible effects of

macroprudential policies on output and price stability, and draws out implications for the conduct of

monetary policy.

2. The paper then presents empirical analysis of these issues. Using cross-country data on

the use of macroprudential policy tools from 2000 to 2011 in 36 countries, the paper assesses

empirically the effects of macroprudential policy on financial variables—such as credit and asset

prices—as well as their effects on the real economy. This analysis also investigates how the effects of

macroprudential policy tools may depend on financial and economic conditions and whether the

strength of effects of macroprudential tools depends on whether the tools are tightened or

loosened.

3. The paper finally collects a number of country case studies that were prepared to shed

light on the interplay between macroprudential and monetary policies in practice. These

examine the experience in Central, Eastern, and South-Eastern Europe, Brazil, Turkey, Korea, and the

United States. Brief summaries of these case studies are in Box 1.

4. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section II considers theory and existing

evidence on policy interactions. Section III presents empirical evidence. Section IV assembles country

case studies on the interplay between monetary and macroprudential policy tools.

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

4

4

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Box 1. Case Studies on Monetary and Macroprudential Policies

Central, Eastern, and South-Eastern Europe. A salient feature of the experience in Central, Eastern, and

South-Eastern Europe ahead of the crisis was a pronounced increase in foreign currency (FX) lending. This

case study examines the experience of five inflation targeting countries in the region and investigates

whether interest rate spreads stimulated the increase in FX lending. It also studies macroprudential policy

responses that were taken to reduce the systemic risk associated with such lending. The study finds that

where interest rates were low relative to advanced country rates, the increase in FX lending was less

pronounced, other things equal. It also finds that the strongest macroprudential measures were effective in

counteracting the increase.

Brazil. Brazil has been an active user of both monetary and macroprudential policies. Its experience during

the post-crisis period illustrates well the complementary relationship between the two policies. Monetary

policy was used countercyclically in macroeconomic management, and macroprudential instruments were

also used to contain the potential buildup of systemic risks from rapid credit growth. As these policies

leaned against the business and financial cycle, synchronized during this period, the policy mix was

appropriate to meet two objectives—price and financial stability—with two instruments.

Turkey. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the Turkish authorities faced a challenging

environment, characterized by widening current account deficits, strong short-term capital inflows, and rapid

credit growth. In response, the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey (CBRT) adopted a new “policy mix”

that emphasized financial stability objectives, while other macroprudential measures were taken only with

some delay. This case study examines the policy outcomes and points to the importance of coordination and

clear communication in responding to building financial imbalances.

Korea. During the 2000s, Korea experienced housing price boom-busts and a sharp increase of short-term

foreign currency (FX) borrowing in its banking system. While the Bank of Korea focused on price and output

stability under a flexible inflation targeting framework, financial imbalances in the housing market were

addressed with targeted macroprudential policy measures, such as limits on loan-to-value (LTV) and debt-

to-income (DTI) ratios. More recently, restrictions on FX derivative positions, and a Macroprudential Stability

Levy were brought in to curb excessive short term foreign currency borrowing. This case study shows that

such macroprudential measures have clear advantages over the use of monetary policy, which is too blunt to

deal with housing market developments and can worsen external vulnerabilities in an economy with a fully

open capital account like Korea

United States. The United States offers prime terrain to study financial instability in the years leading up to

the financial crisis of late 2007. Did an overly loose monetary policy and absence of macroprudential

measures undermine financial stability? The study finds some, though weak, evidence that interest rates

were too low relative to an optimal monetary policy response. It also finds that a relaxation of regulations

and the absence of an institutional framework geared explicitly to financial stability contributed to the

growing leverage of large investment banks, though other factors may also have been at play. Moving

forward, it will be essential to improve the effectiveness of macroprudential policies in advanced economies.

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

5

5

II. INTERACTIONS BETWEEN MONETARY AND

MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICY

A. Policy Interactions––Conceptual Framework

5. Recent advances in analytical modeling offer a simple conceptual framework for

thinking about policy interactions between monetary and macroprudential policies. This

literature examines the interaction between macroprudential and monetary policy in theoretical

(DSGE) models with borrower collateral constraints and a banking sector. In these models, monetary

policy controls the risk free interest rate and macroprudential policy the risk premium, or the spread

between lending rates and the risk free rate.

1

6. A basic result is that, in the presence of macroprudential policy, it is optimal for

monetary policy to stay focused on price stability. In particular, the optimal calibration of the

reaction of monetary policy to output and inflation does not change markedly when

macroprudential policy is also used, and instead remains close to that commonly found in traditional

models without financial sector distortions or macroprudential policy.

7. In practice, macroprudential policy may not be fully effective in containing systemic

risk. The assumption made by the models is that the available macroprudential instrument is

perfectly targeted and fully offsets financial shocks. In practice, this is unlikely to be the case. For

instance, political economy considerations may limit the deployment of certain, unpopular,

macroprudential instruments, in particular when use of the instrument has strong distributional

implications. In addition, institutional arrangements may limit the frequency with which

macroprudential policy may be used, as when parliamentary or political approval is required to reset

an instrument.

8. As a result, monetary policy may still need to respond to financial conditions. Indeed,

in models where macroprudential policy is absent or time invariant, but in the presence of financial

sector distortions, it is optimal for monetary policy to consider financial shocks.

2

In such contexts,

optimal monetary policy responds to the growth in credit (in addition to the output gap and

deviations of inflation from target).

3

By extension, when macroprudential policy is imperfectly

targeted, it can be desirable for monetary policy to respond to financial conditions.

1

This literature includes Baillu and others (2012), Kannan and others (2009), Unsal (2011), Angelini and others (2011),

Bean and others (2010), Christensen and others (2011), and Cecchetti and Kohler (2012).

2

See, for example, Woodford (2011). Kannan and others (2009), as well as Christensen and others (2011), also find

that optimal monetary policy responds to credit when macroprudential policy is switched off.

3

Where there is a response to the credit gap, the optimal sensitivity parameters of monetary policy to the output

gap and deviations of inflation from target do not change markedly.

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

6

6

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

9. In these models, having two policies to achieve both price and financial stability

enhances welfare. Moreover, in practice, especially when capital accounts are fully open, achieving

both objectives with one instrument may not be feasible. For example, when capital inflows

appreciate the currency and lead to imbalances, increases in policy rates cannot reduce incentives

for (foreign exchange) wholesale funding or credit expansion. Conversely, the literature shows that

when monetary policy is constrained or absent, using macroprudential policy in the place of

monetary policy to control output and inflation is inefficient and costly, as it severely constrains the

financial sector and output.

4

10. More generally, the literature points to synergies, rather than conflicts, even if the

optimal policy mix can vary with the type of shock hitting the economy. In the presence of a

financial shock, most models imply that only macroprudential policy should be used since it is more

targeted at the distortion.

5

In the presence of aggregate demand (preference) shocks that induce an

increase in both credit and inflation, both policies are tightened, complementing each other in

responding to the shock. In the presence of productivity shocks, conflicts can arise since a positive

supply shock can lead asset prices and credit demand to rise but dampens goods market inflation.

The optimal policy mix then depends on the strength of the externality from increases in credit to

aggregate financial risks. If this externality is strong, the accommodative monetary policy response

to the productivity shock is complemented by targeted macroprudential policy to contain the build-

up of leverage that may be induced by the shock.

6

11. While structural models offer clear insights into policy interactions, their downside is

their simplicity. This includes the abstraction in the majority of cases from modeling the side

effects of monetary policy on financial stability, described in the next section; and the lack of realistic

modeling of the transmission of macroprudential instruments to financial and output stability, which

is explored further below. Moreover, the adaptation and calibration of models to country

circumstances is often yet to be undertaken and hindered empirically by limited (cross-country)

experiences with both policies.

B. Monetary Policy and Side Effects on Financial Stability

12. It has long been understood that monetary policy can affect financial stability. This

section offers a taxonomy of these––beneficial or adverse––effects. It also considers the factors that

may impact the strength of the effects and explores how well-designed macroprudential policies

have the potential to contain the adverse effects of monetary policy on financial stability.

4

See, e.g., Unsal (2011).

5

As in Baillu and others (2012), Kannan and others (2009), Unsal (2011), Angelini and others (2011), and Bean and

others (2010).

6

As in Christensen and others (2011).

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

7

7

13. Building on the financial markets’ imperfections literature, there are a number of

channels by which monetary policy can affect financial stability. It can affect the tightness of

borrowing constraints and likelihood of default; the risk seeking incentives of intermediaries; and

externalities operating through aggregate price variables, such as asset prices and exchange rates.

Table 1 shows for each channel the prediction from theoretical models of the effects of changes in

the monetary policy stance on financial stability. It also summarizes related empirical evidence.

7

An

appendix in the main paper reviews the empirical evidence in more detail.

Table 1. Monetary Policy Effects on Financial Stability

1/

Sources of

Financial

Instability

Channel

Predicted Effect

( improves stability)

Selected Empirical Evidence

↓r ↑r

Borrowing

Constraints

Balance Sheet

(default)

Channel

Sengupta (2010)

Jiménez and others (2009)

Gertler and Gilchrist (1994)

Asea and Blomberg (1998)

↑r ,

↑r ,

↑r ,

↑r ,

Risky

Behavior of

Financial

Institutions

Risk-taking

Channel

Jiménez and others (2009)

Ioannidou and others (2009)

Merrouche and Nier (2010)

↓r ,

↓r ,

X

Risk-shifting

Channel

Gan (2004)

Landier and others (2011)

↑r ,

↑r ,

Externalities

through

Aggregate

Prices

Asset price

Channel

Altunbas and others (2012)

Del Negro and Otrok (2007)

IMF (2009)

↓r ,

↓r ,

X

Exchange rate

Channel

Hahm and others (2012)

Merrouche and Nier (2010)

Jonsson (2009)

↑r ,

↑r ,

↑r ,

Source: IMF.

1/ ↓r means a decrease of policy rates, ↑r means an increase of policy rates, “ ” means a decline of stability, “ ” an

improvement, and “X” no statistically significant effect.

14. Changes in the monetary stance can affect the tightness of borrowing constraints and

the likelihood of default. Monetary easing relaxes collateral constraints, mitigating financial

distortions both on the demand and supply side of credit. Conversely, a tightening of rates can

adversely affect borrowers’ quality, leading to higher default rates and potentially precipitating a

crisis (Allen and Gale, 2000; Illing, 2007, Goodhart and others, 2009).

15. Changes in the monetary stance can affect the risk-seeking behavior of financial

intermediaries in multiple ways. Two channels may move in opposite directions, as follows:

7

These channels are formalized in theoretical work, but empirical evidence on these effects faces challenges,

including the absence of a counterfactual path for monetary policy and difficulties in telling apart the effects on the

demand and supply of credit. Most of the papers cited in Table 1 can be interpreted as indirect evidence.

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

8

8

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Risk-taking. Low monetary policy rates can create incentives for banks to expand their balance

sheets and reduce efforts in screening borrowers (Borio and Zhu, 2008). They can also lead other

agents to seek more risks in order to achieve higher returns (Rajan 2006). These effects are likely

to be worse if monetary policy is (too) accommodative for too long during expansions. If

monetary policy is expected to be lowered during recessions to support the financial system,

this may create additional incentives to correlate risks (Farhi and Tirole, 2012).

Risk-shifting. Increases in policy rates can reduce intermediation margins, and lead lenders,

especially poorly capitalized intermediaries, to seek more risk (Bhattacharya, 1982). This channel

may be stronger just ahead of a crisis, when intermediary leverage is high and competition limits

the pass-through of policy rates to lending rates. More generally, a flattening of the yield curve

associated with increases in policy rates can lead banks to seek risk in order to maintain profits

(Merrouche and Nier, 2010).

16. Monetary policy can affect externalities operating through aggregate financial prices,

including asset prices and exchange rates. By affecting asset prices and exchange rates, monetary

policy affects the value of collateral, which influences the tightness of borrowing constraints.

Asset prices. Low interest rate can increase asset prices, which can trigger further increases in

leverage and lead to asset price booms, exacerbating the financial cycle (Bernanke and Gertler,

1989). Conversely, a tighter monetary stance can cause collateral constraints to bind, fire sales to

follow, with resulting adverse asset price externalities (Shin, 2005).

Exchange rates. In open economies, interest rate increases can attract capital flows,

appreciating the currency, leading to excessive borrowing in foreign currency and laying the

ground for exchange rate externalities during the depreciation phase (Bruno and Shin 2012,

Hahm and others, 2012).

17. The intensity of these effects can depend on the point in the financial cycle. As financial

imbalances build up, low monetary policy rates reduce current defaults, but can induce banks to

make riskier loans and increase leverage. When rates are increased close to the peak of the financial

cycle, this can induce risk-shifting and borrower defaults. Moreover, incentives to correlate risks due

to the expectation of future monetary easing can be stronger in the upswing of the financial cycle.

18. The strength of the effects can also depend on financial structure and capital account

openness. For example, securitization generally reduces the strength of the effects of monetary

policy on credit extension by banks (e.g., Altunbas, and others 2012). But the importance of risk-

taking and risk-shifting channels may not diminish, since they come to work through both banks

and non-banks. Moreover, in open and financially-integrated economies, domestic monetary policy

has a weaker influence over domestic long-term rates and asset prices, but exchange rate

externalities become more important.

In open economies, high policy rates can encourage capital inflows and foreign exchange

borrowing. In a number of countries in emerging Europe, foreign exchange (FX) lending to

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

9

9

households increased ahead of the crisis, with tighter monetary policy aggravating the situation,

as it provided further incentives for borrowing in FX (case study, Section IV). At the same time,

when the central bank lowers rates to support the economy in a downturn, this can lead to a

depreciation and worsen exchange rate externalities arising from tightening constraints.

As international financial integration increased over the past decades, domestic monetary

control has weakened for both advanced countries and emerging markets. Bernanke (2005)

argued that a global saving glut reduced long-term rates in advanced economies, and that as a

result the relationship between short rates and long rates had become weak (Greenspan

conundrum), thereby reducing the pass-through of policy rates to asset prices.

For emerging economies, similarly, the correlation between domestic short and long rates has

weakened (Moreno, 2008) and the importance of foreign factors strengthened. Increased cross-

border banking contributes to these effects since for cross-border banks, global monetary

conditions seem to matter more than local conditions (Cetorelli and Goldberg, 2012; Shin, 2011).

19. First principles suggest that well-targeted macroprudential policies have the potential

to contain the undesirable effects of monetary policy. Where the side effects of monetary policy

on financial stability are expected to be undesirable, this can create conflicts between financial and

price stability objectives. Appropriate macroprudential policies can attenuate these side effects,

thereby reducing policy dilemmas and creating additional “room for maneuver” for monetary policy.

For most of the channels discussed above, a range of specific macroprudential instruments may

reduce the effect when brought in ex ante.

The impact on defaults from a tightening of monetary policy can be contained by

macroprudential tools, such as a limit on DTI. A conservative DTI ratio may reduce the effect of

increases in policy rates on debt affordability, thereby lessening an unwanted transmission of

increased policy rates to household default rates (Igan and Kang, 2011). This in turn can help

protect bank balance sheets and reduce the force of fire-sale dynamics for asset-backed

securities.

A range of macroprudential measures can affect the risk-taking channel. Increases in capital

requirements or a tight leverage ratio can help contain increases in bank leverage in response to

low policy rates and reduce the incentives to take risk (Farhi and Tirole, 2012). Such measures

also create additional buffers to absorb risks from an erosion of lending standards. However,

where shadow banks are important providers of credit, macroprudential tools are needed that

control leverage both inside and outside of the banking system (United States case study,

section IV). The regulation of margin in securities lending is an example (Kashyap and others,

2010).

Risk-shifting incentives associated with increases in policy rates could also be addressed through

appropriate macroprudential tools. Liquidity measures, such as the Basel Net Stable Funding

ratio, encourage banks to seek stable and longer-term funding. Where funding is longer term,

this can reduce the impact of a monetary policy tightening on lending margins and profits and

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

1

1

0

0

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

attenuate the incentive for intermediaries (banks and non-banks) to seek further risk exposure in

response to increases in policy rates.

8

Capital buffers can also reduce risk-shifting incentives

from a compression of margins (Bhattacharya 1982, Hellmann and others, 2000).

When accommodative monetary policy drives up asset prices, macroprudential measures, such

as limits on LTV ratios, can tame house price boom-busts. When low policy rates encourage

borrowing and greater credit in turn drives up asset prices, a lower LTV ratio can counter this

effect. Some studies have found that a conservative LTV ratio can contain the feedback loops

between credit and house prices (IMF, 2011b). Moreover, studies have found that a tightening of

LTV ratios can slow the rate of house price appreciation, thereby reducing the potential for a

housing bubble to emerge (Crowe and others, 2011; Igan and Kang, 2011; Wong and others

2011).

The policy dilemma that may arise from interactions between domestic monetary policy and

capital flows can be addressed by macroprudential measures. Macroprudential measures can

affect gross flows and help change the composition of flows away from short-term and FX

denominated liabilities issued by banks, thereby reducing the systemic risk associated with

capital flows (Hahm and others, 2012).

9

Examples are FX reserve requirements (RRs)

implemented in Romania and the levy on FX denominated non-core liabilities introduced in

Korea. In addition, where high domestic rates encourage corporations or households to borrow

in FX, macroprudential measures can reduce heightened default risks, including higher risk

weights and tighter LTV ratios, as well as limits on FX lending, as applied in a number of

countries in emerging Europe (case study, section IV).

20. In sum, in its transmission, monetary policy can interact with financial distortions in

several ways, with the net effect on financial stability often ambiguous. Several channels may

be at work, operating simultaneously with their strength varying with the stage of the financial cycle,

financial structure, and other country characteristics. Where the side effects are expected to be

undesirably strong, well-designed macroprudential policies that are brought in ex ante can

attenuate these effects.

8

English and others (2012) find empirically that a flatter yield curve is associated with lower net interest margins, with

the size of the effect increasing in the maturity mismatch between bank assets and bank liabilities.

9

As long as the measures do not affect the size of the net inflow, overall leverage may continue to rise.

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

1

1

1

1

C. Macroprudential Transmission and Effects on Real Economic Outcomes

21. This section presents a closer examination of existing literature on the transmission of

macroprudential policies and traces out implications for monetary policy. This analysis focuses

on tools that have traditionally been used most frequently in emerging markets and those that are

likely to be used most actively in future, in both advanced and emerging economies, such as

dynamic capital buffers, limits on loan-to-value ratios and RRs.

10

For each of these tools, the paper

traces out the transmission to reduced systemic risk, as well as real economic outcomes, and draws

out implications for monetary policy.

11

Capital buffers

22. The main objective of an increase in the dynamic capital buffer is to increase the

resilience of the banking system. The idea is that when credit grows strongly, the quality of the

credit portfolio is likely to deteriorate, increasing the likelihood of future losses. When high credit

growth triggers an increase in the dynamic capital buffer in good times, the buffer can cushion the

effect of losses on bank balance sheets and thus help maintain the flow of credit when losses

materialize.

23. The effect of increases in the dynamic capital buffers on aggregate credit is likely to be

weak, in principle. When credit growth is strong, banks have ample profits that can be used to

build up the buffer through retained earnings. In addition, theory suggests that asymmetric

information and the resulting adverse signaling effects are among the main reasons for banks’

reluctance to issue new equity (Myers and Majluf, 1984; Kashyap and others, 2010) or to cut

dividend payouts (Bhattacharya, 1979). These effects are likely to be weak in good times. Moreover,

since the increase in capital is mandated, adverse signaling effects from a decrease in the dividend

payout ratio or from issuing new equity are likely to be small. On the other hand, since banks must

fear losing profitable business if they increase lending rates or cut exposures outright, they may be

less likely to pursue these strategies to meet the capital buffer.

24. In practice, increases in the buffer may still reduce credit and output for a number of

reasons, which may need to be offset by monetary policy. First, if the increase in the buffer is

brought in fast, banks will not be able to accumulate it through retained earnings alone. Second,

further distortions, such as the tax benefits of equity may make banks reluctant to issue new equity.

In some countries, in addition, banks may not have easy access to capital markets, or are privately or

cooperatively held, making it difficult for these banks to issue new equity. In the presence of such

distortions, some effect on aggregate credit and output is to be expected. Existing evidence

suggests, however, that the effects on output of increases in capital requirements may be relatively

10

The analysis focuses on macroprudential tools whose benefit is seen as containing a “time dimension” of systemic

risk, or the risk of “procyclical” increases in the risk of financial instability.

11

CGFS (2012) provides further analysis of the transmission of macroprudential tools.

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

1

1

2

2

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

modest (BIS 2010, Jimenez and others 2012). This implies that any dampening effect exerted by an

increase in the buffer can be countered by more accommodative monetary policy, if necessary, as

long as monetary policy is effective.

12

25. On balance, stronger effects are likely in bad times when the accumulated buffer helps

sustain the provision of credit to the economy. Existing evidence points to stronger effects of

capital buffers on credit in bad times. Nier and Zicchino (2008) find that a larger capital buffer

mitigates the adverse effect of loan losses on loan growth and that this effect is stronger in crisis

times. Jimenez and others (2012) show that the effects of varying dynamic provisions on credit in

Spain were much stronger in crisis times than they were ahead of the crisis. New results presented in

Section III are also consistent with stronger effects on credit in bad times.

26. Where a dynamic capital buffer is in place, this will therefore reduce the need for

monetary policy makers to offset the effects of tighter credit conditions on output. In

response to a tightening of the availability of credit from October 2008, many advanced country

central banks cut interest rates aggressively in an effort to support the financial system. When

capital buffers are built up ahead of the downturn, the buffers can help sustain the provision of

credit to the economy and reduce the depth of the downturn. The presence of a dynamic capital

buffer may then lessen the risk that monetary policy runs into the constraints posed by the lower

bound on nominal rates and complement monetary policy in bad times, resulting in a smoother

path of monetary policy through the cycle.

27. In addition, when capital buffers have been built up in the upswing of the financial

cycle, the buffers may help keep open the transmission of monetary policy. In the absence of

sufficient buffers, the erosion of capital may lead banks to reduce the supply of credit to the

economy. Even where policy rates are lowered aggressively, this may not be enough to counter

banks’ reluctance to lend. A bigger capital buffer that banks are allowed to run down can help

unblock the transmission of monetary policy to the provision of credit (Turner, 2012).

Loan-to-value ratios

28. Limits on loan-to-value (LTV) and debt-to-income (DTI) ratios are increasingly being

viewed as useful to contain potentially damaging boom-bust cycles in residential housing

markets (Igan and Kang, 2011; IMF, 2011b; Crowe and others, 2011). An LTV ratio imposes a cap on

the size of the loan relative to the value of the property, thereby imposing a minimum down

payment. In principle, even a static, but conservatively calibrated LTV ratio can strongly affect house-

price dynamics. Its effect can be enhanced when the calibration is varied with cyclical conditions in

the housing market (as in Korea and Hong Kong SAR), or when it is complemented with a DTI ratio

12

Complications can arise when capital requirements are tightened in bad (crisis) times, and when monetary policy is

already close to its lower bound. In this case, the risk of deleveraging is greater and cannot easily be countered by

monetary policy.

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

1

1

3

3

(as in Poland and many other countries). A DTI ratio caps total loans to a fixed multiple of household

income and may help contain unsustainable increases in household debt more broadly.

29. These measures have been found successful in containing house price accelerations in

the upswing. Limits on LTV ratios can reduce financial accelerator mechanisms that otherwise lead

to a positive two-way feedback between credit and house prices. A number of cross-country studies

have found that positive shocks to household income or the size of the population translates into

larger house price increases where prevailing leverage ratios are higher (Almeida and others 2005;

IMF, 2011b). Moreover, a number of studies have found that a tightening of LTV ratios can slow the

rate of house price appreciation, thereby reducing the potential for a housing bubble to emerge

(Igan and Kang, 2011; Wong and others, 2011; Crowe and others, 2011). For example, Crowe and

others (2011) find that a 10 percentage point tightening of the LTV ratio leads to a decline in the

rate of house price appreciation of between 8 and 13 percentage points.

30. Where these measures limit house price acceleration and household indebtedness,

they may also dampen the associated increases in aggregate demand, in turn modifying

optimal monetary policy. LTV and DTI measures may reduce the response of residential

investment and household consumption to positive financial shocks. When they reduce the strength

of financial accelerator mechanisms in the upturn, this may allow monetary policy to be somewhat

looser than in the absence of these measures (IMF, 2008).

31. A growing body of evidence also points to the benefit of LTV and DTI ratios in

containing the severity of the property bust when the housing market turns.

In theory, where leverage is high, even a relatively small fall in house prices may lead borrowers

to become underwater. This creates incentives to default strategically, which in turn imparts

further downward pressure on prices. Consistent with this, IMF (2011b) show that across OECD

countries over the 1980 to 2010 period, conditional on a housing bust occurring, the fall in

property prices is less steep where LTV ratios are tight.

A housing bust can put stress on financial intermediaries’ engaged in mortgage credit, and tight

LTV ratios can reduce these impacts. High rates of default can reduce profitability and deplete

banks’ capital cushions. Wong and others (2011) document that, for a given fall in house prices,

the incidence of mortgage default is higher for countries without a LTV ratio limit than it is for

countries with such a tool. They also show that losses sustained by lenders for a given fall in

house prices are lower.

Stress on financial intermediaries can lead to a contraction of mortgage credit and credit more

broadly, adversely affecting both household consumption and business investment. Based on

1960–2007 cross-country data, Claessens, Kose, and Terrones (2008) show that output losses in

recessions accompanied by housing busts are two to three times larger than otherwise.

Moreover, housing busts tend to prolong recessions, as falling house prices act as a further drag

on household consumption and residential investment, while putting financial intermediary

balance sheets under stress.

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

1

1

4

4

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

32. By reducing the depth and duration of the downturn, limits on LTV and DTI ratios can

also lessen the risk that monetary policy will run into its lower bound. When tight LTV and DTI

ratios contain mortgage defaults and losses sustained by financial intermediaries in the wake of a

fall in house prices, this can also reduce output losses from the property bust. A milder downturn

can in turn reduce the need for monetary easing that would otherwise be necessary to counter the

financial headwinds from the property bust. IMF (2008) shows formally that offsetting the

deflationary impact of a negative financial shock requires a larger accommodative monetary policy

response in an economy with a high LTV ratio and a smaller response where LTV ratios are tight.

33. These complementarities are further strengthened by the effects of LTV and DTI ratios

on the transmission of monetary policy. As seen in many advanced countries since the crisis

broke, when a large fraction of borrowers have high LTV mortgages, this can clog up the

transmission of lower policy rates on conditions in mortgage markets after the bust. After a fall in

house prices, high LTV borrowers will find themselves unable to refinance their loans since the

principal exceeds the value of their property. These borrowers will then not be able to take

advantage of lower mortgage rates that an easing of monetary policy may help bring about. A

tighter LTV constraint going into the property bust can mitigate this and help strengthen the

transmission of monetary policy after a house price falls (Geanakoplos, 2010).

34. Limits on DTI and LTV ratios can also affect developments in the composition of

output that are not easily controlled by monetary policy. First, a tightening of these measures

can, by slowing housing transactions and dampening house price growth, reduce the share of

residential construction in GDP (see Section III for empirical evidence). Second, to the extent that

these measures contain increases in household leverage, they can help control a rise in debt-

financed consumption spending that worsens the current account. Along with other policy measures

(such as structural and fiscal policies), LTV and DTI policies may thus contribute to a reduction of

external imbalances.

Reserve requirements

35. Central banks can use variations in the level of RRs to affect broader credit conditions.

When RRs are remunerated below the policy rate or are unremunerated, a variation in the level of

the requirement imposes a tax on lending. This tax is expected to increase the spread between

lending and deposit rates as banks pass on increased costs to their customers (Gray, 2011; Tovar

and others 2012; Glocker and Towbin, 2012a). Independent of the incidence, since the tax will lead

to a fall in deposit supply, or a contraction of loan demand, or both, the amount of credit provided

to the economy is expected to fall. By increasing the spread between lending and deposit rates, RRs

will then lower the amount of credit provided to the economy, acting as a “speed limit.”

36. Inflation targeting central banks will typically offset the impact on banking system

liquidity and interbank interest rates of a change in RRs. The volume of open market operations

can be adjusted to offset the impact on banking system liquidity and to keep interbank rates close

to the target rate. But even if the monetary effect of changes in RRs is sterilized, there can be a

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

1

1

5

5

macroprudential effect, which works through an increase in the spread between lending and deposit

rates. See further the case studies for Brazil and Turkey in Section IV of this paper.

37. Empirical studies tend to find evidence in support of an effect on credit. Vargas and

others (2011) study the experience in Colombia and find that RRs have a strong and lasting effect on

lending rates charged on business loans. Glocker and Towbin (2012b) estimate a structural vector

autoregressive (VAR) model for the Brazilian economy. They find that a one percentage point

increase in the RRs leads to a peak increase in the spread between lending and deposit rates of

80 basis points. Moreover, domestic credit falls on impact by about 2.5 percent and remains below

trend for close to two years. The empirical exercise reported in Section III is also consistent with a

significant effect on credit.

38. However, increases in RRs do not increase resilience and can have unintended side

effects. Unlike an increase in capital requirements, an increase in RRs has no impact on the

resilience of the banking system to loan losses. In addition, an increase in RRs can exacerbate risk-

shifting incentives. When RRs squeeze profitability this can lead banks to shift into higher margin,

but higher risk segments, in an effort to restore return on equity. In Turkey, for instance, relatively

aggressive increases in RRs in early 2011 may have further spurred banks’ consumer lending, which

was ultimately addressed by increases in regulatory risk weights on such lending (Turkey FSAP and

case study).

13

39. An increase in RRs can lead to nominal depreciation and affect capital inflows. In small

open economies, increases in the monetary policy rate will tend to attract capital inflows and lead to

an appreciation of the currency. Increases in RRs tend to have the opposite effects, since they will

tend to decrease returns on domestic and FX deposits (Glocker and Towbin, 2012a).

14

Using data

from Brazil, Glocker and Towbin (2012b) find that an increase in the reserves requirement by one

percentage point leads to a 2 percent depreciation of the domestic currency. Evidence presented in

Tovar and others (2012) confirms the effects of RRs on exchange rates, even if their results point to a

more transitory depreciation. New evidence presented in Section III suggests that RRs have the

potential to affect the composition of capital inflows, away from bank portfolio flows.

40. The effects of increases in RRs on output are ambiguous in theory. The rise in bank

lending rates should tighten credit and lead to a decline in investment spending. However, the fall in

deposit rates may decrease domestic savings and increase consumption. Moreover, any

depreciation resulting from the increase in RRs would lead to an increase in net exports that boosts

aggregate demand. This implies that while an increase in RRs unambiguously lowers aggregate

13

These adverse effects of increases in RRs contrast with bank capital requirements. An increase in the latter leaves

banks’ return on total assets unaffected and in general reduces rather than increases banks’ incentives to take risk.

14

Since an increase in RRs will lead to a decline in deposit rates, under uncovered interest parity, net capital inflows

will fall. An alternative explanation is that the tax reduces total expected return for foreign investors (Gray 2011).

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

1

1

6

6

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

credit, its net effect on output may be relatively small (Glocker and Towbin, 2012a).

15

Empirical

results presented in Section III suggest that there is no measurable effect of an increase in RRs on

output.

41. RRs provide a potential way to curb excessively strong credit growth, while effects on

other economic variables are quite different from that of monetary policy. In contrast to

increases in policy rates, an increase in RRs can reduce excessive credit growth without attracting net

capital inflows and appreciating the exchange rate. Moreover, when increases in RRs dampen capital

inflows, this can give greater room for maneuver for monetary policy to increase interest rates, as

has been the experience in Peru (Tovar and others 2012).

42. Equally, in economic downturns, a relaxation of RRs can stimulate credit growth

without this leading to a depreciation of the exchange rate or capital outflows. This contrasts

again with the effects of an easing of the monetary policy rate, which is likely to contribute to a fall

in the currency and capital outflows, especially in bad times (Federico, Vegh, and Vuletin, 2012).

43. In sum, the transmission of macroprudential policy tools and the implication for the

conduct of monetary policy may differ with the tools considered.

Some tools, including the dynamic capital buffer and limits on LTV ratios, increase the resilience

of the economy against aggregate shocks, mitigating the effects on output of a credit crunch

and housing bust. This can reduce the need to for accommodative policy in such scenarios and

makes it less likely that monetary policy will hit the constraint imposed by the lower bound. It

can also help keep open monetary transmission channels in a downturn scenario.

When capital requirements and LTV ratios are tightened in upturns, they may have effects on

credit and asset prices, and hence, potentially on aggregate output. Where these effects are

sizable, they can be offset, as necessary, by more accommodative monetary policy.

RRs may be a useful complement to monetary policy, especially in open economies, since use of

this tool can control credit growth. This can give greater room for maneuver for monetary policy

in the face of potentially destabilizing capital flows. The effect of an increase in RRs on output is

ambiguous, though, and empirically found to be small.

III. EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

A. Macroprudential Policies—Effects on Credit, House Prices, and Output

44. This section describes empirical analysis of the effects of macroprudential policy

measures. Several empirical studies show that macroprudential policy instruments can be effective

15

Empirically, Glocker and Tobin (2012b) find that increases in RRs increase unemployment in Brazil, but that this

effect is half that from an equivalent variation in the monetary policy rate.

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

1

1

7

7

in addressing systemic risk externalities, if used appropriately. Lim and others (2011) find that

macroprudential instruments may reduce the correlation between credit growth and GDP growth,

and several studies show that limits on LTV and DTI ratios can curb the feedback loop between

mortgage credit availability and house price appreciation. However, few studies consider differential

effects across macroprudential tools. Moreover, there is to date only a very limited analysis of any

macroeconomic effects of the use of macroprudential tools.

45. Our analysis expands on the existing literature in several ways.

First, the direct effects of macroprudential measures on financial outcomes—credit growth and

housing price appreciation—are tested.

Second, we perform analysis of “side effects” of the macroprudential tools on economic growth,

residential investment, and capital inflows.

Third, we investigate whether the strength of these effects differs with measures of the

economic and financial cycle.

Model specification and data

46. We focus on (varying) capital requirements (CR), limits on LTV ratios, caps on DTI

ratios, and RRs. For each macroprudential instrument, an index variable is constructed. This index

increases by 1 whenever an instrument was introduced or tightened and decreases by 1 whenever

the instrument is loosened, resulting in a series that looks like a step function. The index variable

captures both semi-quantitative effects and the average treatment effects of the instrument.

Countries and periods in which instruments are not used are included as counterfactuals and help in

identifying the effects of key control variables. The information required on the use of the

instruments is obtained and extended from the 2010 IMF survey (Lim and others, 2011).

16

47. A fixed-effect dynamic panel regression is used with the following specification:

∆

,

·

,

·∆

,

·

,

··

,

,

For each country ,

,

and

,

represent changes of outcome variables and a time-series index

of one of the four macroprudential measures respectively, where the coefficient captures the

effects of macroprudential measures on the outcome.

,

denotes a set of control variables and

·

,

is included to capture the interaction between the control variables and the

macroprudential instruments. Throughout, we include time-fixed effects, to account for common

variation across countries, as well as country-fixed effects, to account for time-invariant country-

16

We would like to acknowledge Ivo Krznar’s contribution to this section. The data comes mostly from Krznar and

others (forthcoming) and the regressions extend the framework in Arregui and others (forthcoming).

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

1

1

8

8

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

characteristics. Our regressions also control for monetary policy rates and dummy variables

denoting phases of credit and economic cycles.

17,18

48. The measurement of the effects of policy changes on both financial and aggregate

variables is subject to well-known endogeneity problems. This issue is shared by most existing

studies on the effects of macroprudential policy study (e.g., Lim and others, 2011). When

macroprudential policy responds to credit and asset prices, rather than output, this bias should in

principle be stronger when measuring the effect on credit and asset prices—as does much of the

existing literature—and weaker when investigating aggregate effects—which is the focus here.

Moreover, as long as the problem does not differ across tools considered it may not affect

comparisons across tools in their relative effects. Throughout, we lag all policy variables by one

quarter in an attempt to address endogeneity biases.

19

Nonetheless, we take the results as only

suggestive of the relative strength of the effects across tools, rather than as a reliable measure of

the size of each effect.

20

49. Quarterly data from 2000 to 2011 were used for 36 countries,

21

including 21 emerging

market economies (EMEs) and 15 advanced economies (AEs).

22

Most of the data are collected

from official and commercial sources, such as IFS, central banks, national statistical offices, Haver

Analytics, and CEIC database, being specified along the results. Detailed information on countries

which have used macroprudential policies can be found in Table 2.

17

Variables in the form of dummies are constructed to control for the stages of financial and economic cycles. First, a

credit bust is classified as a stage with either of the two following conditions being satisfied: (i) the deviation from a

HP filtered trend is smaller than 1.5 times its standard deviation; or (ii) the quarterly credit growth rate is lower than a

long-run average by 1.5 times its standard deviation. Second, a recession dummy is equal to one on the quarters

when the output gap, using the HP filter, is negative for previous six consecutive quarters.

18

In addition, interactions between monetary and macroprudential policies are analyzed, but no significant empirical

evidence is found. We created dummy variables indicating whether the monetary stance is tight, or whether it is

loose and estimated interactions between the macroprudential tools and the monetary policy dummies. This result is

in line with results obtained by Dell’Ariccia and others (2012). Coefficients on the interaction terms are unstable and

rarely significant across all macroprudential tools. Similarly we do not find that effectiveness of macroprudential

policy depends on the monetary and FX regime, echoing results already documented by Lim and others (2011).

19

In order to try to reduce the endogeneity problem, one quarter lagged policy variables are used for the main

results, and a robust test is conducted with concurrent variables, which shows similar results.

20

As mentioned in Lim and others (2011), the estimation of a dynamic panel by OLS with country and time fixed

effects will be biased, since by construction there is a positive correlation between the lagged dependent variable

and the unobserved individual level effects. We dropped the lagged dependent variable as a robustness check, and

found that the main results do not change materially.

21

The countries in the sample are as follows: Argentina, Austria, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia,

Croatia, Estonia, Hong Kong SAR, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Latvia, Malaysia, Mexico,

Netherlands, Norway, Peru, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Singapore, Slovak Republic, South Korea, Spain, Sweden,

Thailand, Turkey, Uruguay, and U.S.

22

As of September 2012, the number of countries in the sample with each de facto exchange rate regime is as

follows: free floating (10), floating (15), fixed (3) (of which currency board (2) and conventional peg (1)), and others (8)

(of which crawl like (3), other managed (4), and stabilized (1)).

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

1

1

9

9

Table 2. Use of Macroprudential Measures Across Countries

Sources: Lim and others (2011) and IMF staff.

Advanced Economies Emerging Market Economies

(Free)

Floating

Fixed

Other

Managed

(Free) Floating Fixed

Stabilized or

Other

Managed

Capital

requirement

Estonia,

Israel,

Korea

Ireland,

Spain

—

Argentina, Brazil,

Mexico, India,

Thailand, Turkey

Bulgaria

China,

Malaysia,

Croatia

Limits on LTV

ratio

Canada,

Norway,

Korea,

Sweden

Hong Kong

SAR,

Netherlands

Singapore

India, Thailand,

Hungary,

Romania, Turkey

Bulgaria,

Latvia

China,

Malaysia

Caps on DTI

ratio

Canada,

Korea,

Norway

Hong Kong

SAR

—

Thailand, Poland,

Romania,

Hungary, Serbia

— —

Reserve

requirements

Korea — —

Argentina, Brazil,

Chile, Colombia,

Peru, Uruguay,

India, Indonesia,

Romania, Serbia

Bulgaria

China,

Croatia,

Russia

Results—effect on financial variables

50. Investigating the effects on credit growth, we find statistically significant effects for

both (varying) capital requirements and RRs (Table 3). For capital requirements in particular, we

find that the effect on credit growth is stronger during credit busts. For a subsample containing

EMEs only, we find that limits on LTV and DTI ratios are also associated with lower credit growth. In

this subsample, the effect of RRs is little changed relative to the full sample. The effect of capital

requirements on credit growth weakens, but remains stronger during credit busts.

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

2

2

0

0

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Table 3. Effects of Macroprudential Measures on Credit Growth

1/

Source: IMF staff estimates.

1/ Green, orange, and yellow color in each cell indicate significance at 1, 5, and 10 percent level, respectively.

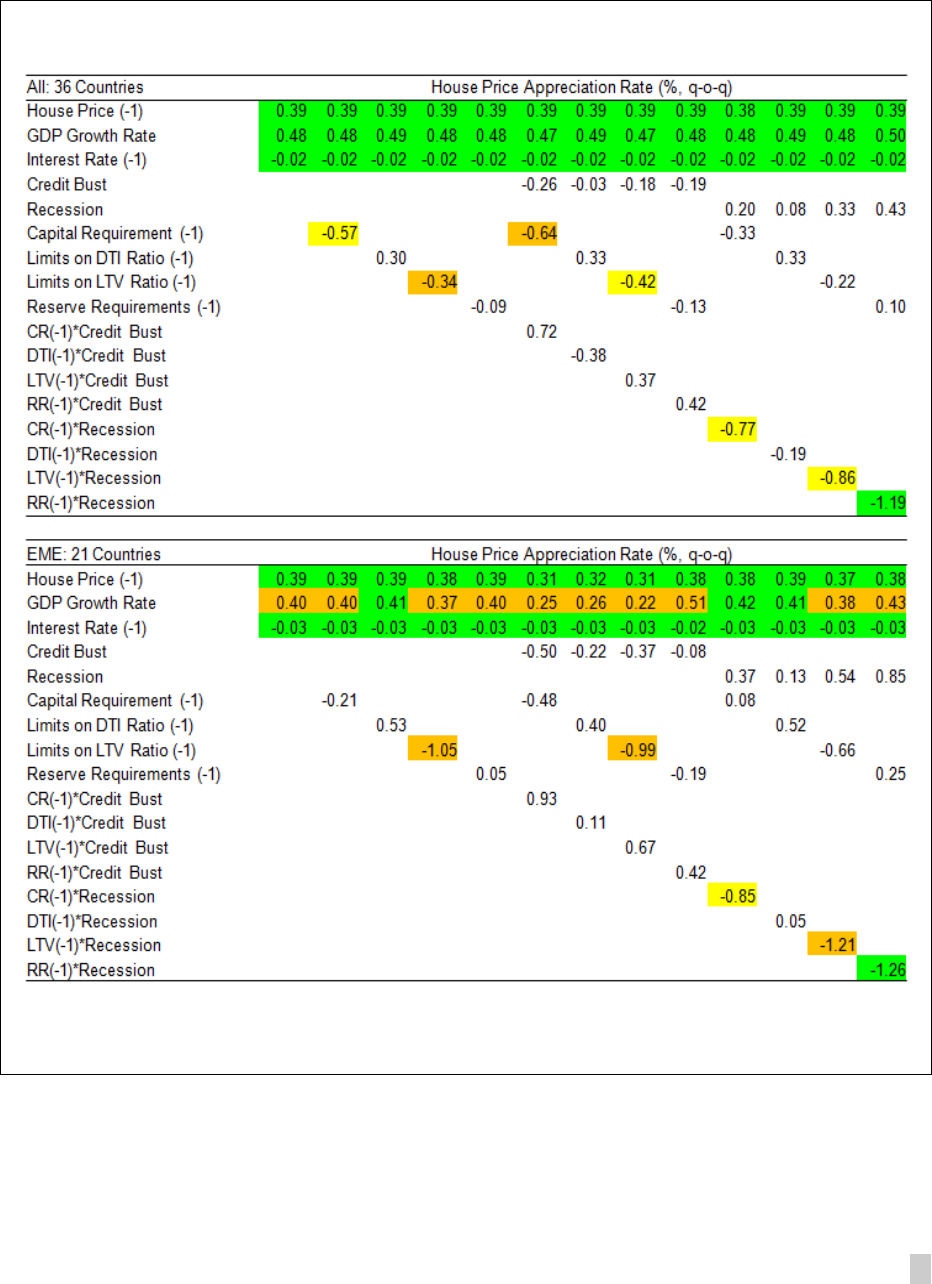

51. When investigating effects on house price appreciation rates we find statistically

strong effects for limits on LTV ratios and capital requirements, but not for RRs. This suggests

that in our sample, variation in capital requirements might have been specifically targeted at

housing credit in a number of countries, such as higher risk weights on mortgage loans, while RRs

by construction do not differentiate between asset classes, and are therefore less likely to have an

effect on a particular asset price. Interestingly, the effects of macroprudential tightening (or

loosening) on house prices is estimated stronger during recessions across most measures, while for

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

2

2

1

1

house prices the stage of the credit cycle appears to play less of a role. Throughout, the evidence for

direct effects of variation in the DTI ratio on house prices is in general not as strong (Table 4).

Table 4. Effects of Macroprudential Measures on House Price Appreciation

1/

Source: IMF staff estimates.

1/ Green, orange, and yellow color in each cell indicate significance at 1, 5, and 10 percent level, respectively.

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

2

2

2

2

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Results—effect on macro variables

52. Turning to the effects on output, the results of the main panel regressions suggest

that limits on LTV ratio have an impact on output growth, and that this may work through a

negative impact on investments in construction (Table 5). After controlling for monetary policy

rates and foreign exchange rates, the coefficient on limits on LTV ratio across different regression

equations is statistically significant in the whole sample. Especially for EMEs, a higher LTV ratio is

associated with smaller investments in construction.

Table 5. Effects of Macroprudential Measures on Output Growth and Residential

Investment

1/

Source: IMF staff estimates.

1/ Green, orange, and yellow color in each cell indicate significance at 1, 5, and 10 percent level, respectively.

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

2

2

3

3

53. For other macroprudential tools, we find little evidence of a direct effect on output.

The coefficients on capital requirements, caps on DTI ratio and RRs are not statistically significant,

indicating weaker effects on output than found for the LTV ratio. It is possible that for capital and

RRs statistically significant effects could be picked up in larger samples or using a different study

design. However, the results also confirm existing studies that tend to find modest effects of these

tools on output. See BIS (2010) and Glocker and Towbin (2012b), respectively.

54. By contrast, throughout, we find that variation in the policy rate has a statistically

strong effect on output growth. These findings suggest that some macroprudential policy tools

may be able to separately target a specific component of domestic demand, unlike monetary policy,

but that the effect of these macroprudential tools on aggregate output is more limited. Conversely,

the policy rate affects all economic activity regardless of which sector is vulnerable to systemic risks,

and may then have stronger effect on output growth.

55. It is possible that the effects are too small to show up as statistically significant in our

panel analysis. An indirect way of gauging the effects on output is to extrapolate from the effect on

credit growth. A number of empirical studies show the effects of credit supply shocks on output

growth, ranging from 0 to 0.34, that is, a one percent decline in credit supply induces a drop in the

GDP growth rate of up to 34 basis points. Thus, combining with results in Table 5, some

macroprudential policy instruments may still affect output growth to a meaningful degree.

Results—effects on capital flows

56. We finally turn to an investigation of the effect of macroprudential measures on

capital inflows. Monetary policy is often said to be constrained in open economies since policy rate

hikes to contain financial exuberance are likely to trigger more capital inflows. Some

macroprudential tools, on the other hand have been found in the literature to be useful to affect

gross flows and the composition of capital inflows.

57. We specifically investigate the determinants of portfolio investments. The

specification is similar to those employed before. However, we now account for the effect of the

spread between the domestic rate and the federal funds rate. In particular, we create a dummy

variable that indicates whether this spread is unusually high, relative to the average in the country

concerned.

58. The results of this exercise are contained in Table 6. We find that where the interest

spread is high, this stimulates portfolio inflows. Moreover we do not find that capital requirements,

LTV and DTI ratios have any effect on the strength of portfolio inflows. By contrast, we find

statistically strong evidence that increases in RRs reduce portfolio inflows in emerging economies

with floating exchange rates. These results chime with those found elsewhere in the literature:

increases in RRs lead to a depreciation of the currency. They can also, more mechanically, arise when

RRs apply to FX debt securities issued by banks.

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

2

2

4

4

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Table 6. Effects of Macroprudential Measures on Capital Inflows

1/

Source: IMF staff estimates

1/ Green, orange, and yellow color in each cell indicate significance at 1, 5, and 10 percent level, respectively.

B. Effects of Macroprudential Policy Measures—Symmetric or Asymmetric?

59. This section describes additional empirical tests to investigate potential asymmetries

in the effectiveness of macroprudential measures. From a policy perspective, it is important to

ascertain whether the size of the effect of a tightening of a macroprudential policy tool differs from

that of a loosening of the tool, or whether the effectiveness of macroprudential measures is

symmetric.

60. Table 7 documents the number of instances, for each macroprudential tool, in which

the measures were tightened and loosened. This suggests that for most measures, the number of

tightening events is far greater than that of loosening events. This is a key limitation for the

empirical analysis, since if there are few instances of loosening this will reduce the power of any test

of differential effects. Inspection of the table suggests that this is a major issue in particular for

capital requirements and DTI ratios. For RRs in particular, the situation is somewhat better with a

ratio of tightening to loosening events roughly 3 to 1.

Table 7. Number of Macroprudential Measures—Tightening or Loosening

Total Sample Tightening Loosening

Capital Requirements 1728 21 3

Limits on DTI Ratio 1728 17 2

Limits on LTV Ratio 1728 34 5

Reserve Requirements 1728 28 9

Sources: Lim and others (2011) and author’s extension.

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

2

2

5

5

61. The potential for asymmetric effects is gauged by interaction exercises. The basic

strategy followed is to interact the measure of the tightness of the macroprudential tool (the step

function used previously) with dummy variables that indicate, for each change in the step function,

whether the change is an increase (tightening) or a decrease (loosening). We examine the issue of

symmetry for the key financial variables investigated before. That is, our dependent variables are

credit growth as well as the growth of asset prices.

62. Figure 1 suggests that loosening events tend to occur from 2008, when in many

countries there would have been financial stress as a result of the global financial crisis. This

suggests that countries are more likely to loosen macroprudential policy tools when the financial

system is in need of support. Our empirical analysis takes account of the resulting potential

measurement bias by including dummy variables that indicate financial stress, such as credit bust,

asset price busts and recession, as well as interactions with these variables that capture differential

effects of macroprudential policy in times of stress.

63. Overall we cannot reject the hypothesis that the effect of macroprudential policy tools

is symmetric, rather than asymmetric. The results on credit growth suggest that, if anything, a

loosening of RRs has a stronger effect on credit growth than a tightening of RRs (Table 8). However,

Figure 1. Number of Macroprudential Measures—Tightening or Loosening

-2.0

-1.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

2000Q1 2002Q3 2005Q1 2007Q3 2010Q1

Number of Tightening or Loosening of Capital

Requirements (Sample: 36 countries)

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Tightening

Loosening

-2.0

-1.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

2000Q1 2002Q3 2005Q1 2007Q3 2010Q1

Number of Tightening of Caps on Debt-to-Income Ratio

(Sample: 36 countries)

Source: IMF staff calculations.

-3.0

-2.0

-1.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

6.0

7.0

2000Q1 2002Q3 2005Q1 2007Q3 2010Q1

Number of Tightening of Limits on Loan-to-Value Ratio

(Sample: 36 countries)

Source: IMF staff calculations.

-5.0

-4.0

-3.0

-2.0

-1.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

2000Q1 2002Q3 2005Q1 2007Q3 2010Q1

Number of Tightening of Reserve Requirements

(Sample: 36 countries)

Source: IMF staff calculations.

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

2

2

6

6

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

for the other macroprudential tools, there are no measurable differences. The results on house

prices suggests that, if anything, a tightening of LTV ratios appears to have a stronger effect than a

loosening does, while, for other macroprudential tools there is no measurable difference (Table 9).

64. These results need to be interpreted with great caution. As pointed out above, for some

of the macroprudential tools, in particular capital requirements and DTI ratios, the incidence of

Table 8. Effects of Macroprudential Policy Stance on Credit Growth

Source: IMF staff estimates.

1/ Green, orange, yellow color in each cell indicate significance at 1, 5, and 10 percent level, respectively.

Credit Growth Rate (%, q-o-q)

Credit Growth Rate (-1) 0.40 0.39 0.39 0.39 0.39 0.39 0.39 0.40 0.40 0.39 0.39 0.39 0.39

GDP Growth Rate 0.23 0.23 0.23 0.23 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.22 0.21

Interest Rate (-1) -0.04 -0.05 -0.04 -0.04 -0.04 -0.04 -0.04 -0.04 -0.04 -0.04 -0.04 -0.04 -0.04

Credit Bust 0.88 0.43 0.55 0.49

House Price Bust -0.69 -0.66 -0.71 -0.58

Recession

-0.62 -0.56 -0.65 -0.59

Capital Requirement (-1) -0.33 -0.49 -0.56

Limits on DTI Ratio (-1) -0.25 -0.20 -0.17

Limits on LTV Ratio (-1) -0.07 -0.04 -0.04

Reserve Requirements (-1) -0.28 -0.23 -0.29

Other Measures(-1) -0.13

-0.23 -0.27 -0.21 -0.14 -0.22 -0.29 -0.21 -0.14 -0.23 -0.31 -0.22

CR(-1)*Credit Bust -1.44

DTI(-1)*Credit Bust 1.90

LTV(-1)*Credit Bust 0.11

RR(-1)*Credit Bust 0.41

CR(-1)*House Price Bust 0.74

DTI(-1)*House Price Bust 0.82

LTV(-1)*House Price Bust 0.45

RR(-1)*House Price Bust -0.10

CR(-1)*Recession 0.20

DTI(-1)*Recession -0.02

LTV(-1)*Recession 0.24

RR(-1)*Recession 0.14

CR(-1)*CR_tight(-1) 0.20 0.13 0.14

DTI(-1)*DTI_tight(-1) -0.11 0.10 0.08

LTV(-1)*LTV_tight(-1) 0.14 0.11 0.12

RR(-1)*RR_tight(-1) 0.19 0.16 0.17

CR(-1)*CR_loose(-1) -0.77 -1.11 -0.74

DTI(-1)*DTI_loose(-1) -0.67 -0.12 -0.07

LTV(-1)*LTV_loose(-1) -0.48 -0.35 -0.41

RR(-1)*RR_loose(-1)

1.78 1.83 1.62

T-test (H0: two coefficients equal) 0.94 0.70 0.65 1.69 1.00 0.28 0.49 1.75 0.84 0.19 0.57 1.53

P-value 0.35 0.49 0.51 0.09 0.32 0.78 0.63 0.08 0.40 0.86 0.57 0.13

THE INTERACTION OF MONETARY AND MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES: BACKGROUND PAPER

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

2

2

7

7

loosening events may be too small to detect differences that are statistically significant in a small

sample. That is, it is quite possible that differences could be detected in samples with a greater

number of observations.

Table 9. Effects of Macroprudential Policy Stance on House Price Appreciation

House Price Appreciation Rate (%, q-o-q)

House Price (-1) 0.39 0.38 0.39 0.40 0.39 0.38 0.38 0.38 0.38 0.38 0.39 0.40 0.39

GDP Growth Rate 0.48 0.48 0.48 0.48 0.48 0.39 0.41 0.40 0.41 0.48 0.48 0.47 0.49

Interest Rate (-1) -0.02 -0.02 -0.02 -0.02 -0.02 -0.02 -0.02 -0.02 -0.02 -0.02 -0.02 -0.02 -0.02

Credit Bust -0.26 -0.03 0.31 -0.20

House Price Bust -4.89 -4.88 -5.09 -4.99

Recession 0.20 0.02 -0.18 0.39

Capital Requirement (-1) -0.65 -0.53 -0.39

Limits on DTI Ratio (-1) 0.37 0.29 0.39

Limits on LTV Ratio (-1) 0.04 -0.28 -0.21

Reserve Requirements (-1) -0.01 0.00 0.18

Other Measures(-1) 0.03 -0.25 -0.04 -0.17 -0.07 -0.29 -0.11 -0.22 0.03 -0.25 -0.05 -0.12

CR(-1)*Credit Bust 0.70

DTI(-1)*Credit Bust -0.43

LTV(-1)*Credit Bust -0.97

RR(-1)*Credit Bust 0.46

CR(-1)*House Price Bust -1.41

DTI(-1)*House Price Bust -2.57

LTV(-1)*House Price Bust -0.28

RR(-1)*House Price Bust -0.72

CR(-1)*Recession -0.72

DTI(-1)*Recession -0.20

LTV(-1)*Recession 0.38

RR(-1)*Recession -1.10

CR(-1)*CR_tight(-1) -0.02 0.13 0.11

DTI(-1)*DTI_tight(-1) 0.11 -0.01 0.03