Building a resilient economy

Analysing options for systemic change

to transform the world’s economic and

nancial systems after the pandemic.

Building

a resilient

economy

institute fo

r

future-fit

economies

Page intentionally left blank.

Page intentionally left blank.

Project Consortium

ZOE-Institute for future-t economies, Germany

New Economics Foundation, United Kingdom

Wellbeing Economy Alliance, United Kingdom

The project was led by ZOE-Institute for future-t economies (ZOE) in close

cooperation with the New Economics Foundation (NEF) and the Wellbeing Economy

Alliance (WEAll).

Please cite as:

Barth J. and Coscieme L., Dimmelmeier, A., Kumar C., Mewes S., Nuesse I., Pendleton

A., Trebeck K. (2020): Analysing options for systemic change to transform the world’s

economic and nancial systems. ZOE-Institute for future-t economies: Bonn.

Transparency

This paper is based on a review commissioned by the WWF.

The nancial support of Partners for a New Economy (P4NE) is greatly appreciated.

ISSN: 2627-9436

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all people who supported us in the development of this report.

First and foremost, the WWF team, who developed the initial study concept and

provided advice and expertise throughout (Toby Roxburgh, Karen Ellis, Ray Dhirani,

Angela Francis, Dominic White, Stefano Esposito). We would also like to thank the

participants of the survey and the webinar where we presented a preliminary version

of the report. Thanks also to all those who assisted us in the background during the

development. These include Lisa Boll, Olivia Davis, Anais Gradinger, Christoph Gran,

Elias Huland, Benedikt Hummel and Lukas Salecker.

Layout and design concept

Drees + Riggers

Photos

Cover: Juliane Liebermann, p. 19: Myles Tan, p. 20 / 21: Adrian Infernus, p. 46 / 47:

Cagatay Orhan, p. 53: Julia Stepper (all photos taken from unsplash.com)

Copyright

© ZOE-Institute for future-t economies, 2020

The views expressed in this document are those of the authors. This publication and

its contents may be reproduced as long as the reference source is cited.

Contact details

Jonathan Barth,

Institute for future-t economies gUG (haftungsbeschränkt),

jonathan.barth@zoe-institut.de

Content

Executive Summary 8

Introduction 11

Background: The economics of biodiversity

and the need for systemic change 13

Addressing biodiversity loss 13

Understanding and dening systemic change 15

Methodology 17

Part 1: Overview of barriers and

policy proposals for changing the

economic and nancial system

20

Policy and governance 24

Barriers to policy change 24

Options for systemic change 25

Finance 28

Barriers to a sustainable transformation

of the nancial system 29

The role of policy in setting nance on

course for tackling today's challenges 30

Business 33

Barriers to implementing sustainable

and fair business models 33

Policy options to drive sustainable business behaviour 34

Citizens 36

Barriers for change towards sustainable

living and drivers for unsustainable behaviour 36

Policy actions to enable sustainable living 37

Interim conclusion: thinking about and

engaging in systemic change 40

Part 2: Policy options for the UK

to move towards a resilient economy

46

Rationale behind this prioritisation 50

1. A Wellbeing Budget for the UK 54

2. Modernising UK’s Fiscal Rules 58

3. A New National Investment Authority 61

4. Mandatory Financial Risk Assessments and Disclosure 64

5. Green Credit Guidance 68

6. Land Value Tax 71

7. Resource Caps and Biodiversity 74

8. Environmental Border Tax 78

Interim conclusion: The interplay of policy proposals 82

In place of a conclusion: A story of hope 86

Endnotes 88

Appendix 112

8

Executive SummaryBuilding a resilient economy

Content ↑

Executive Summary

In 2020, the world’s governments acted at an

impressive scale and speed to mobilise resources

in response to COVID-19. By April, they had col-

lectively assigned US $ 9 trillion to buffer against

the economic impacts of the pandemic. In the UK

alone, € 176.7 billion were made available as an

immediate scal response.

As these eye-watering sums illustrate (and

those associated with the banking crash in 2008

reinforce), dealing with a crisis is very cost-

ly, in economic terms as well as regarding social

impacts. Therefore, where a crisis is foreseeable –

as in the case of climate change and increasing bio-

diversity loss, societies should invest in preventa-

tive measures.

Science shows us that humanity’s impacts

on the planet are intensifying and environmen-

tal trends are heading in the wrong direction. In

response, there have been calls for systemic

interventions from prominent international agen-

cies including the United Nations Environment Pro-

gramme, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate

Change (IPCC) and the Intergovernmental Sci-

ence-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosys-

tem Services (IPBES).

These agencies recommend a rapid transition

towards an economy that’s low-carbon, resource-

light and that restores nature. They are promot-

ing the need for a fundamental reform of our eco-

nomic systems, so that equality, environment, and

wellbeing become core to the way our economies

function. It’s an agenda that has been endorsed

by mainstream actors such as the World Econom-

ic Forum, the Financial Times and the Economist.

Many reports, ideas and proposals make the

case for the required changes. What has been

missing is a better understanding of how system-

ic change can be put into operation and, given the

urgency and interdependency of the issue, how the

UK can effectively support a fundamental trans-

formation of its economic system towards a resil-

ient economy.

This report it is an attempt to ll this gap. The follow-

ing chapters (and the research underpinning them)

focus on the role of government and policy in deliver

-

ing systemic change. We outline where public policy-

makers should place the emphasis in order to trans-

form the world’s economic and nancial systems most

effectively to mitigate future environmental crises.

The report proposes a set of policies the UK

government could implement to amplify impact

and ensure long-term systemic change – both for

its domestic economy and at an international level.

There is no “silver bullet” solution to the multiple

crises we face, and many changes will be required,

involving governments, investors, businesses and

the public alike – so the policy package we out-

line is a blueprint to deliver systemic change in

the current policy context. It should be regarded

as a basis for discussion to demonstrate the scale,

nature and interlinkages of the changes required.

We start by categorising the key areas for sys-

temic intervention that can shift behaviour in the

longer term into four sections (policy, nance,

business, and citizens), as illustrated in Table 1.

The → rst part of our report provides a summa-

ry of almost 300 transformative proposals split

into these four categories. Each proposal has the

potential to address the socioeconomic root caus-

es of today’s crises through policy changes that

have cross-cutting and transformative impact.

Building on this comprehensive list of propos-

als we set three key criteria to identify the most

promising policies:

1. Relevance: their relevance and topicality in

the UK context.

2. COVID-19 suitability: the extent to which

they could support a sustainable economic

recovery from COVID-19.

3. Transformative potential: the impact they

have on driving long-term systemic change.

Policy Finance Business Citizens

Multidimensional

indicators, moni-

toring capacity, and legal

frameworks: ensure

political decision making

addresses the environ-

ment and wellbeing with

equal weight on the

economic aspects.

Fiscal policy and

growth independ-

ence: increase the space

for scal interventions to

support a green and just

transition and decouple

economic stability from

economic growth.

Limiting power

and empowerment

for change: reduce

economic and democratic

power imbalances.

Mandates and legal

interpretations:

include environmental

and social objectives in

the targets of public insti-

tutions such as central

banks and development

banks.

Metrics for the

long-term: integrate

environmental categories

and extend the time hori-

zon in risk assessments.

Shifting

Protability:

internalise the costs of

environmental damage.

Sustainable invest-

ment and innova-

tion: shift investment and

techno logy from resource-

intensive activities to

those that are less resource-

intensive but more

labour-intensive.

Non-nancial

disclosure, report-

ing and accountability:

include environmental

objectives in business

reporting standards.

Sustainable

business models:

Support business models

that focus on sustainabil-

ity and well being and

create a level playing

eld.

Sustainable

consumption

alternatives: shift from

unsustainable to sustain-

able consumption.

Sufciency: limit

the total level of

consumption.

Affordability

and fairness: reduce

inequality and ensure

that all are capable of

meeting their basic needs

and of participating

socially.

9

Executive SummaryBuilding a resilient economy

Content ↑

Using this analysis and input from experts in poli-

cy, academia and business, we propose a package

of eight mutually supportive areas of reform in the

→ second part of the report. These policies would

help to signicantly accelerate the transition towards

a resilient economy for the UK and internationally:

1. A → wellbeing budget for the UK that redenes

what we value in our economy and conse-

quently allocates a greater share of public and

private resources towards environmentally

sustainable and socially benecial outcomes.

2. A → modernised set of government scal

rules in the UK that ensure the availability

of sufcient resources to complement the

wellbeing budget. This will enable the UK

government to borrow more at the current low

interest rates and invest in the low-carbon and

resource-efcient sectors that will sustain the

economic development of the country over the

coming decades.

3. Further backing for redirecting money to help

fund the green transition, via a new → UK

national investment authority. This will play

an active role in the market by investing public

resources towards specic missions or

outcomes (such as meeting the UK’s net zero

target).

Table 1: Fields of action and intervention clusters of recommendations from the literature review

10

Executive SummaryBuilding a resilient economy

Content ↑

4. On a nancial level, this shift in investments

is accelerated through → mandatory nancial

risk assessments and their disclosure for

private banks that integrate non-traditional

environmental risks into their accounting and

risk assessment frameworks.

5. The disclosure of these risks is also a

precondition for → green credit guidance. By

factoring climate and ecological risks into their

asset purchases and collateral frameworks,

central banks will help shift investments from

harmful activities to green sectors.

6. A → land value tax to generate a new source

for nancing investments and generating

resources to support low-income households.

This policy will have negligible effects on eco-

nomic activity, but will help correct wealth and

power inequalities. Its taxes windfall increases

in land value while increasing the efciency

of land use in rural areas, and will reduce soil

sealing and the fragmentation of landscape.

7. Additional scal revenues from → resource

caps. These ensure that increases in resource

efciency translate into an absolute rather

than a relative reduction in resource use. In

doing so they help control biodiversity loss

and ensure ecosystems can recover naturally

to a more sustainable state.

8. → Environmental border taxes that put a

higher price on imports of environmentally

harmful goods. These will ensure that the

domestic economy is competitive, at the same

time they will reduce carbon emissions while

protecting biodiversity.

For each of these policies we identify several exist-

ing stakeholder coalitions and upcoming political

opportunities where they could be rened, promot-

ed and secured. Some require much greater inter-

national cooperation and are therefore more chal-

lenging, while others could be enacted immediately.

The policies presented here are mutually sup-

portive. Most address several of the intervention

areas listed in Table 1. A wellbeing budget for the

UK, the national investment authority, mandatory

nancial risk assessments and a green credit guid-

ance all aim to increase and strengthen investment

in the green economy. A modernised set of govern-

ment scal rules, a land value tax, and resource

caps create the necessary scal leeway. Resource

caps ensure that these policies are effective in

reducing resource use through absolute limits

and a dynamic steering effect via prices. Lastly, a

land value tax is one option among many to ensure

social acceptance, while environmental border

taxes aim to support domestic economic actors.

The recovery from COVID-19 presents a fork

in the road for governments. Bouncing back to

the pre-COVID days isn’t good enough. We can-

not afford to continue to tinker at the edges with

policies that achieve incremental change or are no

longer t for purpose. As the environmentalist Bill

McKibben solemnly noted, “winning slowly is the

same as losing” in the context of climate change.

The research, analysis and synthesis presented

here offers a sample of the bold and transform-

ative policies we need to bounce forward and to

address the multiple crises we face collectively.

To do so, government, investors, businesses and

citizens need to make choices. Together, they need

to put in place regulation that breaks our depend-

ence on fossil fuels and extractive economic activi-

ties and propels the UK along a carbon-neutral, low

resource and high wellbeing pathway. This report

is an invitation. We are aware the proposals are

far-reaching. But we are convinced they are nec-

essary. To mitigate the costs of future crises, we

need the courage to do something new. With this

report, we invite you to dare, so that the prosperi-

ty of today will benet our children tomorrow and

we can give them a greater chance to thrive on a

bountiful planet.

11

IntroductionBuilding a resilient economy

Content ↑

» COVID-19 has shown that avoid-

ing crises is not just a moral issue

– it is also an economic question. «

Crises tend to encourage short-term thinking.

1

When facing a crisis, people tend to react impul-

sively to end it – be it in relationships, business,

nance or policy. This has been no different during

the COVID-19 crisis. Many governments respond-

ed quickly and with extensive effect. By April 2020,

leaders around the world had collectively mobi-

lised $ 9 trillion to buffer against the economic

impacts of lockdown measures.

2

In the UK alone,

€ 176.7 billion were made available as an immedi-

ate scal response to the crisis.

3

The scale of these investments is impressive.

But at the same time, the COVID-19 crisis has

made clear how much crises can cost. Only through

such unprecedented public investment and by rad-

ically restricting public life – closing kindergartens,

schools and businesses – could the worst be pre-

vented. The countries that did not react swiftly and

underestimated the crisis, such as Sweden, have

paid for this with many lives.

4, 5

The actions focused on the short-term saved

lives. However, while politicians respond to the

immediate dangers, there is a direct lesson to be

learnt: Crises are expensive, and they can cause

economic disaster. Societies would, therefore, do

well to invest in preventative measures.

Some crises, like COVID-19, are difcult to

anticipate. Others, however, are foreseeable – cli-

mate change and increasing biodiversity loss, for

example. In the interest of long-term economic

stability, policymakers must face this fact today

and work to limit climate change and the break-

down of ecosystems. Not only because doing so

can decrease the risk of future pandemics

6

: as

COVID-19 has demonstrated, avoiding crisis is not

just a moral issue, but also an economic question.

Many international scientic organisations, includ-

ing the IPCC

7

, the IBES

8

and the recent WEF report

on “The Future of Nature and Business”

9

, have high-

lighted that a fundamental transformation of today’s

socio-economic systems is needed to mitigate cli

-

mate change and biodiversity loss. They provide a

broad consensus on the main areas needing reform

– ranging from policy and nance to private sector

business and lifestyles. What has been missing is a

better understanding of how systemic change can

be operationalised and, given the urgency and inter

-

dependency of the issue, how the UK can effective-

ly support a fundamental transformation.

We have conducted a qualitative expert-led assess-

ment of 60 sources within the global literature on

systemic change. From this literature review, we

derived 270 policy proposals from across 12 topic

clusters, pertaining to four stakeholder groups:

policy, nance, private sector business and peo-

ple. Of these, we have selected eight key policies

for a more detailed elaboration, based on three

criteria: feasible and topical in the UK (relevance),

contribute to recovery from the COVID-19 crisis

(COVID-19 suitability) and have high transforma-

tive potential (transformativity).

Introduction

With this report, we seek to close this gap.

Our work aims to provide:

1. A denition of systemic change

2. An overview of the main policy areas

needing reform, of barriers to change

and transformative policy options

3. A set of eight policy priorities for

the UK that could also inspire

international action

Aim of the report

12

IntroductionBuilding a resilient economy

Content ↑

This report contributes to multiple policy discus-

sions. The options outlined here add to the list of

options for change in the Dasgupta Review, com-

missioned by the UK Treasury, to address the bio-

diversity crisis. This analysis also provides guid-

ance for the effective implementation of the UK’s

net-zero legislation, circular economy strategies

and COVID-19 recovery programs.

We focus on policy actions aimed at adjusting

the structure of the economic system through legal

frameworks or legislation, to influence behaviour

i. e. actors’ collective decision making and in doing

so achieve far-reaching change. This recognises

that institutions are performative: the economic

and institutional framework is a key determinant

of how funds are invested, how and what business-

es produce and how people live and consume.

The report is structured as follows:

1. Chapter one presents our interpretation of the

main challenges that are rooted in the eco-

nomics of biodiversity, which we will present

here drawing on the insights of The Dasgupta

Review

10

. We then provide our denitions of a

resilient economy and systemic change.

2. Chapter two provides a short synopsis of the

methodology used in the literature review and

the stakeholder consultation.

These introductory chapters are followed by two

parts that summarise the results:

• Part 1 provides an overview of the barriers

that hinder systemic change, categorised into

four areas of action: policy, nance, business,

and people. In this chapter, we also sum-

marise the boldest and most transformative

policy solutions to overcome these barriers,

that we found in literature.

• Part 2 further elaborates on the eight key

policy proposals in detail and explains the

rationale behind their prioritisation. Every

policy proposal includes a section on

implementation and the associated barriers

and enablers, inspirational practices, windows

of opportunity and potential stakeholder

coalitions.

• Chapter Five explores how systemic change

is as much about narratives of change and

collaboration, as it is about policymaking.

Many policymakers know that current

measures will not be enough to tackle

today’s environmental crisis, but, in the

face of groupthink, only a few dare to

call for more ambition. With this report

we hope to encourage those involved in

public administration to speak up.

The report is an invitation to question and

consider new solutions. We do not claim

to have found all the solutions. Rather, we

aim to start a necessary discussion to think

outside the box. We are aware that some

of the solutions we present may seem

unusual or too ambitious. However, we

believe that the time has come to discuss

more transformative measures in the polit-

ical arena, and doubt that anything less

would sufce to address the magnitude of

today’s challenges. The costs of inaction

are too high.

An invitation to think about

systemic change

13

Background Building a resilient economy

Content ↑

» The extinction rate has

accelerated enormously, being

up to 100 times higher than in

the past. «

A recent study by the Potsdam Institute for Cli-

mate Change showed that limiting global warm-

ing to below two-degrees Celsius, as agreed in the

Paris Agreement, would be economically efcient

11

,

while an abundance of literature has conrmed

that costs of climate change will be astronomical.

12

While such studies are subject to uncertainty, mod-

elling, data and valuation choices, they point in the

same direction: the costs of climate change will

be high. Some of these costs are already evident

today. One consequence of climate change is the

devastating loss of natural habitats and the asso-

ciated ecosystem services. Together with resource

consumption, land-use change, pollution and inva-

sive species, these drivers have brought the global

ecosystem to the brink of collapse.

13

Ecosystems are responsible for purifying water

and air; providing food, wood, and biomass; regu-

lating climate and delicate water cycles; and pro-

viding natural amenities that humans use for recre-

ation and education. Take bees, for example: They

contribute between $ 233 billion to $ 577 billion

to global food production and support basic eco-

system functioning through their pollination activ-

ities

14

, this economic and ecological value goes

largely unnoticed and unprotected. All these valu-

able ecosystem services are at risk. While current

extinction rates for species are hard to assess, they

may lay somewhere between 1–2 every week

15

.

There is wide agreement that the extinction rate

has accelerated enormously, being up to 100 times

higher than in the past.

16

For example, in 2003, New York has

designated a huge nature reserve and

$ 150 million annually for its preservation

– but not for moral reasons. The nature

reserve puries water and the construction

of a comparable water purication plant

to replace this natural service would cost

$ 8 to 10 billion. Preserving biodiversity

is similarly economically efcient.

Addressing biodiversity loss

» Economic growth is not the goal

in and of itself, but a means of

reaching a number of other goals,

which collectively create economic

stability. «

To understand the economics of biodiversity and

the value of nature, HM Treasury (the UK Depart-

ment of Finance) recently commissioned a report

on the “economics of biodiversity”. Dasgupta dis-

cusses two scenarios for ending the degradation of

the biosphere by 2030, which depend on the “ef-

ciency with which we convert the biosphere’s goods

and services into GDP”.

17

In a “Green Growth” sce-

nario, this efciency would need to almost quad-

ruple, from 2.5 % to 9.1 % by 2030 – an unprece-

dented and unlikely rate of innovation. He there-

fore outlines a second scenario, an economy with

constant economic output (GDP) from now until

2030, where efciency would “only” need to dou-

Background

The economics of biodiversity and

the need for systemic change

14

Background Building a resilient economy

Content ↑

ble – a still unlikely, but more likely scenario. The

second scenario, essentially a “stagnating econo-

my” by current standards, is a headache for econ-

omists, especially in a crisis period.

Pillars of economic and political stability, includ-

ing servicing debts, investment, providing jobs and

ghting inequality, all seem to demand economic

growth. Economic growth is not the goal in itself,

but a means of reaching a number of other goals,

which collectively create economic stability.

The social, economic, and political aspects of

the current economic system demand growth to

ensure stability in the short term. However, in pur-

suing short-term economic growth, policymakers

put long-term stability at risk – by trading in envi-

ronmental health and function, transgressing plan-

etary boundaries and risking costs for public budg-

ets from the environmental crisis.

Economic Stability and Resilience

Stability is a rather static concept. First and fore-

most, it means that important system variables

such as unemployment, inequality or temperatures

have a predictable level of variation around a mean.

To talk about how policy can escape the dilemma of

choosing whether to preserve short-term or long-

term stability, we must introduce another concept:

“resilience”. Resilience adds a dynamic component

to the concept of stability. While stability is about

the magnitude and strength of change, resilience

denes the ability to cope with change, especially

massive change such as shocks and crises. Stabili-

ty in the long-term can therefore be achieved both

by limiting the size of change or by developing an

ability to adapt to and recover from change.

Inspired by Andrew Mitchell

18

, we dene resil-

ience as “the ability to absorb and recover from

shocks”. Long-term stability requires a resilient

economy. An economy that is able to react to mas-

sive change and at the same time reduce the risk

of such change. For the post-COVID recovery to

create a resilient economy, it must transform both

structures and means of living to enable the sys-

tem to react to large shocks, while also reducing

the risk of such shocks.

In this sense, out of all the dimensions of resil-

ience

19

, two aspects of a resilient economy are cen-

tral to this report:

1. Safeguarding environmental resilience:

A resilient economy reduces the risk of future

environmental shocks and enhances

environmental resilience through a reduction

of drivers of biodiversity loss. Green inno -

vation and a structural transformation of the

economy towards sustainable business

models and lifestyles can reduce pressure

on the environment. Investment in ecological

function and recovery can boost both

ecological as well as economic resilience,

if employment and income are coupled with

a healthy environment.

2. Strengthening socio-economic resilience:

By safeguarding environmental resilience,

a resilient economy reduces the long-term

economic risks of environmental crisis. At the

same time, a resilient economy increases its

capacity to recover from shocks by liberating

its stability from the need to grow. A resilient

economy can ensure employment generation,

equality and debt reduction even in a stagnat-

ing economic environment. Such resilience

would require rethinking how we generate

wellbeing and rearranging how we pursue it,

as well as how debt is managed, how jobs are

created, and how inequality is reduced.

15

Background Building a resilient economy

Content ↑

Strategies for addressing

the biodiversity loss

To pave the way for a resilient economy, two

central strategies are required:

1. Green innovation: We need huge leaps

in green innovation to increase material

productivity and efciency, as specied

by Dasgupta, to allow businesses to

produce and society in general to

enjoy as much material prosperity as

is available for distribution. Within the

ecological limits of the planet, policies

that encourage green innovation can

reduce the negative ecological effects

of economic activity and could enable

a transition to a less resource-intense

and climate-friendly economy, as

sought by the UKs Net-Zero Regulation

and the Circular Economy Package.

2. Growth independence: However, while

green innovation has to increase,

policymakers today must prepare for

the fact that these innovations are likely

to still not be sufcient, as recognised

by Dasgupta. It is possible that

ecological collapse can only be avoided

by a courageous restructuring of

today’s economic systems: decoupling

economic and political stability from

economic growth.

The matter of which of these strategies is

the right one is highly disputed.

20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25,

26, 27

Given the uncertainty of the future, we

must apply both rather than debate which

one is right.

Understanding and dening

systemic change

Many researchers, including the IPCC

28

, the IPBES

29

and the WEF

30

have highlighted that transformative

change is necessary to mitigate the acceleration of

the climate crisis and biodiversity loss. They agree

on the main areas of reform, ranging from policy

and nance to business and lifestyles. However,

what is missing thus far, is a better understanding

of how to operationalise systemic change.

We dene systemic change as institutional change

31

that drastically decelerate or mitigate the break-

down of ecosystems, either directly through pol-

icies that protect and restore natural habitats or

indirectly, e. g. through policies that address the

drivers of biodiversity loss like climate change.

Douglass North denes institutions as “con-

straints that structure political, economic and

social interaction. They are made up of formal con-

straints (constitutions, laws, property rights), infor-

mal constraints (sanctions, taboos, customs, tra-

ditions, codes of conduct), and their enforcement

characteristics.”

32

In this report, we go beyond the cultural and

informal dimensions of institutional change. Often,

responsibility is redirected to the people’s cul-

ture. In those cases, the assumption is that people

have to change their values rst, which would then

translate into different policies afterwards.

33

In our

assessment, we recognise the reciprocal nature of

the interaction between formal and explicit institu-

tions like policy, regulations, laws, agreements and

informal value systems and culture.

34

We assume

that policy can drive cultural change, rather than

only being an outcome of it. This, however, does

not take anything away from the necessity of infor-

mal cultural change independent of policy.

16

Background Building a resilient economy

Content ↑

Criteria for systemic change

Systemic change can be understood as changing the formal and explicit

(policies, practices, resource flows) as well as informal and semi-implicit

(power dynamics, relationships and connections) and implicit (mental

models) institutions of today’s economies.

35

In order to be considered systemic

changes, proposed institutional changes must full the following criteria:

1. Structural: Increase the relevance of sustainability and wellbeing aspects in

formal institutions like governance processes, legislation and international

agreements (explicit level).

2. Root-cause related: Address the root causes of today’s environmental and

social challenges (semi-implicit and implicit level): power imbalances, lack

of valuation of nature, growth dependence, narrow value systems in society,

business, nance and policy, and mindset.

3.

Cross-cutting: Influence the behaviour of the majority of actors within

different economic areas (policy, business, nance, citizens) across different

economic sectors (manufacturing, agriculture, energy …) on a long-term

basis, rather than changing the behaviour of only one single actor.

4. Transformative: Can be incremental in the short-run (e. g. biodiversity

labels for nancial products), if they contribute to systemic change in

the long-run (e. g. directing investments across sectors into nature conser-

vation) and help overcome path dependencies that create lock-ins

in existing structures.

17

MethodologyBuilding a resilient economy

Content ↑

To identify a set of key policies for systemic change

toward a resilient economy, we conducted a qual-

itative expert-led assessment of literature on sys-

temic change, building on our experience in the

eld of transformation sciences and new econom-

ics. In doing so, we conducted the following steps:

1. Identication of sources

Firstly, we identied 60 sources on systemic

change from the global literature based on expert

input. Criteria for the selection of sources can be

found in the appendix.

2. Identication of barriers

and transformative policy

proposals / options

Secondly, we identied 270 policy proposals from

these sources. Our literature review concentrated

on proposals for systemic changes, as dened in

the previous chapter.

From this set of proposals, we identied 12 topic

clusters on systemic change along the four clusters

of actors. These are:

• Policy: multidimensional indicators,

monitoring capacity, and legal frameworks;

scal policy and growth independence;

limiting power and empowerment for change.

• Finance: metrics for the long-term; mandates

and legal interpretations.

• Business: protability, investment and

innovation; disclosure, reporting and

assessment; business models.

• Citizens: sustainable consumption

alternatives; sufciency; affordability and

fairness.

Part One of the report will describe the clusters

and associated policies in more detail.

36

In terms of

content, we have enriched the chapters with addi-

tional sources, when an important aspect was still

missing.

3. Denition of eight key

policies for the UK

Out of these 12 clusters and associated proposals,

this report elaborates on eight key policies that:

• are feasible & topical in the UK (relevance),

• contribute to recovery from the COVID-19

crisis (COVID-19 suitability),

• have a high-transformative impact

37

(transformative potential).

At the same time, additional conditions apply to the

whole set of policies, rather than single policies:

• Balance: To nd the balance between feasi-

bility and transformative impact the overall

set of policies includes at least one less

feasible, but highly transformative proposal.

• International dimension: To account for the

UK’s international role, at least one proposal

should have an international dimension

attached.

• Side effects: The set of policy should be com-

plemented with proposals to reduce negative

side effects of other proposals, to ensure

consistency (e. g. environmental border taxes,

land taxation)

Methodology

18

Building a resilient economy

Content ↑

4. Expert consultation

In order to “sense-check” the policy proposals that

emerged from the literature review and from expert

input, we conducted a stakeholder poll amongst

leading policy experts, academics and commenta-

tors who work on relevant questions in the UK and

beyond. We invited almost 100 participants and

received a response rate of approximately 30 %.

Participants in the survey were asked to:

• Reflect on whether the shortlist of proposed

policy changes met our criteria for being

both transformative, and possible, in the UK

context.

• Nominate the three policy changes they would

be most likely to advocate for and why, and

to point to any policies we should consider

adding to our list.

• Advice as to what strategy and approach

would help to secure adoption of the

respective policies in the UK.

While not a large-scale representative poll, this

deliberate, strategic sampling of professionals

with relevant expertise has provided condence

in the suite of policies we set out below. To aug-

ment the poll input, we also posed similar ques-

tions to a different set of policy experts, including

UK government ofcials, at a webinar hosted by the

WWF in June 2020.

Part 1

Overview of barriers

and policy proposals for

changing the economic

and nancial system

This part provides an overview of the main areas of reform, as well

as barriers and transformative policy options, categorised into four

areas of action: policy, nance, business and citizens.

22

IntroductionBuilding a resilient economy

Content ↑

Drawing on our assessment of the global liter-

ature on systemic change, this part provides an

overview of the main areas of reform, as well as

barriers and transformative policy options.

To this end, we consider four elds of action in the

following four sub-chapters: Policy, Finance, Busi-

ness and citizens. The literature offers a wide range

of insight on what prevents these actors from

changing their behaviour and what policy can do

about it.

We faced two challenges when synthesising

the literature. The rst challenge were the highly

differing levels of abstraction of proposals found

in the literature, ranging from abstract propos-

als such as “internalise environmental costs” to

very concrete proposals such as “increase equity

requirements for unsustainable credits”. The chal-

lenge was therefore to align proposals to a similar

level of abstraction. The second challenge was to

identify the target group for policy proposals. For

example, in the case of the proposal to “ban adver-

tising of environmentally harmful products”, the

question of whether the proposal is attributed to

the target group that implements the policy (busi-

ness) or target group that should change its behav-

iour (citizens).

To align levels of abstraction and consistently

assign target groups, we identied 12 interven-

tion clusters for policy makers (see Table 1). The

clusters are to be understood as objectives, the

achievement of which influences the behaviour of

each actor. Some proposals in the literature are

directly reflected in the objective, others in the

associated policy proposals.

A detailed summary of all literature sources can

be found in the → Appendix.

It is important to stress that these clusters are all

interwoven. There are many synergies but also

many conflicts between them. Many of the goals

can only be achieved in tandem with others. For

example, consumption change is only possible

through the availability of product alternatives, as

well as the purchasing power required to access

them. Power cannot only be directly restricted

through prohibition, but it can be influenced indi-

rectly through tax structures and new corporate

models. By cross-referencing, we point out possi-

ble links between the objectives in the chapter.

Introduction

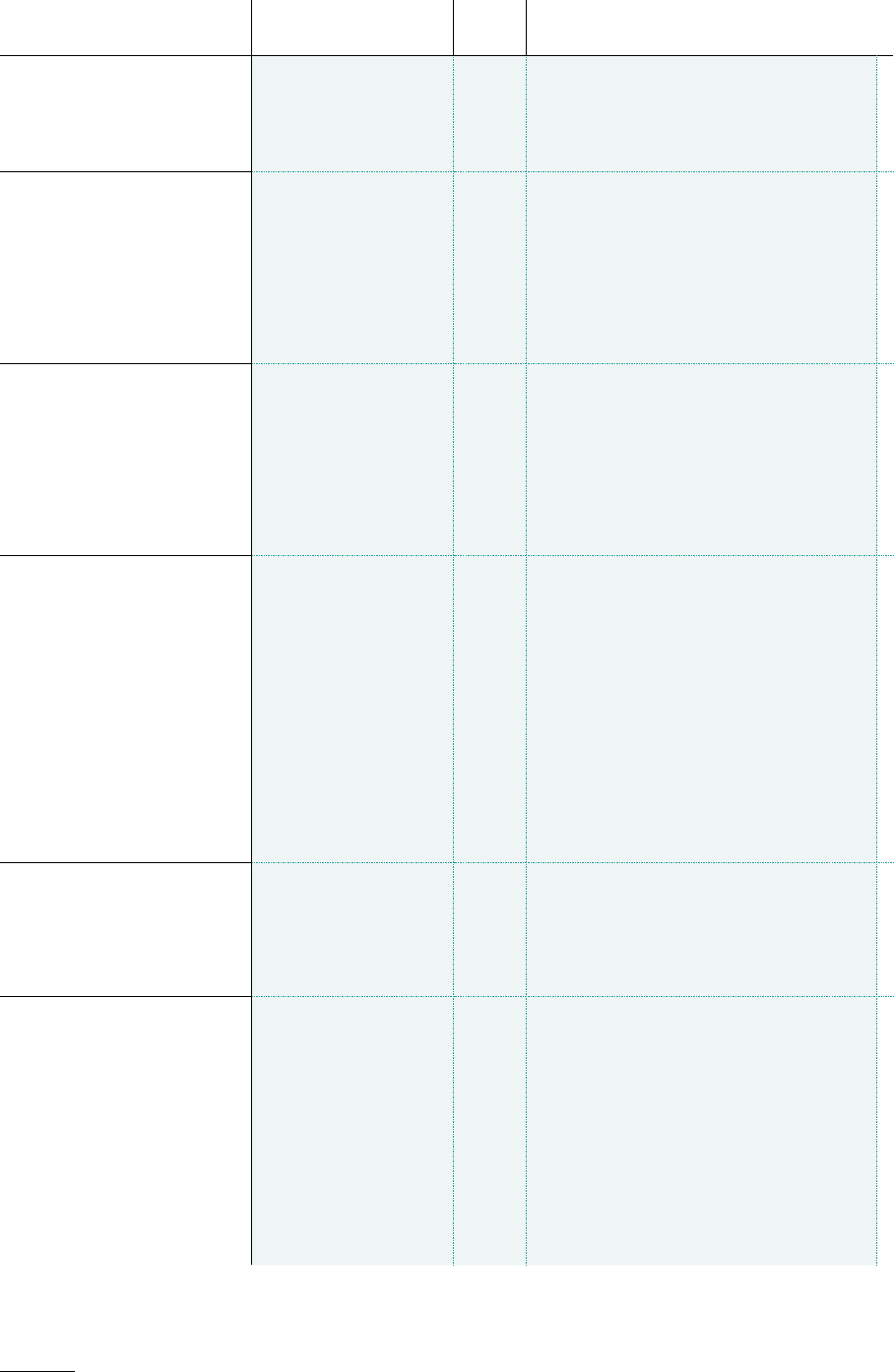

Policy Finance Business Citizens

Multidimensional

indicators, moni-

toring capacity, and legal

frameworks: ensure

political decision making

addresses the environ-

ment and wellbeing with

equal weight on the

economic aspects.

Fiscal policy and

growth independ-

ence: increase the space

for scal interventions to

support a green and just

transition and decouple

economic stability from

economic growth.

Limiting power

and empowerment

for change: reduce

economic and democratic

power imbalances.

Mandates and legal

interpretations:

include environmental

and social objectives in

the targets of public insti-

tutions such as central

banks and development

banks.

Metrics for the

long-term: integrate

environmental categories

and extend the time hori-

zon in risk assessments.

Shifting

Protability:

internalise the costs of

environmental damage.

Sustainable invest-

ment and innova-

tion: shift investment and

techno logy from resource-

intensive activities to

those that are less resource-

intensive but more

labour-intensive.

Non-nancial

disclosure, report-

ing and accountability:

include environmental

objectives in business

reporting standards.

Sustainable busi-

ness models:

Support business models

that focus on sustainabil-

ity and well being and

create a level playing

eld.

Sustainable

consumption

alternatives: shift from

unsustainable to sustain-

able consumption.

Sufciency: limit

the total level of

consumption.

Affordability

and fairness: reduce

inequality and ensure

that all are capable of

meeting their basic needs

and of participating

socially.

23

IntroductionBuilding a resilient economy

Content ↑

Table 1: Fields of action and intervention clusters of recommendations from the literature review

24

Policy and governanceBuilding a resilient economy

Content ↑

» Governments have often

fallen short of implementing

policies that translate agreed

environmental and social

objectives into action. «

Policy and governance are one central lever in

bringing about a resilient economy. By setting

legal and institutional frameworks, governance

shapes people’s attitudes and behaviour, and the

interactions between actors (including govern-

ments, nancial institutions, business and civil

society).

38

Policy could either reproduce existing

inequalities or support low-income groups in the

transition to a more sustainable society. Policy can

also incentivise or disincentivise certain invest-

ment, innovation, production, and consumption;

making it a key measure in the effort to overcome

path-dependencies that lock in current modes of

unsustainable production, consumption, and gen-

eration of wellbeing.

39

Governments have often fallen short of imple-

menting policies that translate agreed environ-

mental and social objectives into action. While

objectives such as the Sustainable Development

Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Agreement are impor-

tant steps towards a resilient economy, , the world

is not well placed to achieve most of the SDGs.

40

Similarly, global policy commitments to reduce

greenhouse gas emissions are insufcient to halve

GHG-emissions by 2030, which is required to limit

global warming to 1.5 °C.

41

Even the existing weak

climate pledges are unlikely to be achieved. The

policy efforts of the UK, the second largest con-

tributor to CO

2

emissions in the European Union

(10.7 %), have fallen short. The Paris Agreement

binds the UK to reducing emissions by at least

40 % of 1990 levels by 2030, and in June 2019

the UK adopted a net zero emissions reduction

target for 2050. Achieving any of these targets

remains unlikely, especially given that the UK’s

expenditures into climate mitigation ($ 100 billion)

decreased by 35 % between 2014 and 2017.

42, 43

Challenges

Barriers to policy change

It remains difcult for most governments to pro-

mote policymaking that is suitable for tackling

the complex challenges of the 21

st

century, for a

myriad of reasons. An assessment of the literature

can be summarised in two clusters: Governance &

political value systems, and power imbalances.

Compartmentalised governance

and short-term focused political

value systems

Firstly, managing the global commons in the face

of international economic competition requires

collective action and enforcement. The non-bind-

ing nature of international climate agreements,

with unclear or inadequate compliance rules, has

not succeeded in raising political ambition at a

national level to take meaningful climate action.

44

Secondly, one of the reasons for this lack of

interest in stronger international agreements are

political value systems and the associated gov-

ernance processes that prioritise short-term eco-

nomic impacts of policies, rather than long-term

environmental and other social impacts. Many

policies lack an evaluation of long-term environ-

mental and social impacts and are shaped accord-

ing to a short-term agenda of economic growth –

even though long-term ecological and social harm

also translates into immense scal expenses down

the line. Economic growth is associated with high

levels of wellbeing, debt reduction, lower inequal-

Policy and governance

25

Policy and governanceBuilding a resilient economy

Content ↑

ity and employment generation. Therefore, it is

seen as the preeminent means to achieve the most

fundamental socio-economic policy objectives.

This and a range of further lock-ins, such as media

attention, geopolitical power competition, pri-

vate interests and lobbying, make it very difcult

for policymakers to break away from economic

growth as a policy objective and argue in favour of

a wider set of indicators and policy measures.

45, 46

Thirdly, political value systems that prioritise

short-term economic policy impacts are tied to

economic attitudes and theories in public institu-

tions, which stem from a narrow reading of eco-

nomics. Economists shape how policymakers per-

ceive and measure the world, affecting the deci-

sions they make.

47, 48, 49, 50

The uncompromising

focus on economic growth is one example.

51

Anoth-

er is the focus of public policy on market-based,

supply-side solutions to economic problems For

example, prior to the COVID-19 crisis, policymak-

ers – both globally and in the UK – were convinced

that solutions would surface through the free mar-

ket, which policy should not excessively regulate.

52,

53

This reading made it difcult to implement regu-

latory measures such as bans or obligations. These

may be economically less cost-effective, but they

are effective in terms of their impact.

Fourthly, certain features of existing demo-

cratic systems pose additional barriers to long-

term oriented policymaking. To ensure re-elec-

tion, political agendas tend to focus on actions with

measurable impacts during their term.

54

Power imbalances

These structural lock-ins of policy and governance

systems are reinforced by actors pursuing short-

term prots and translate into power imbalanc-

es. In the UK, 0.1 % of business receives 47.8 %

of total revenues and provides 39.5 % of the coun-

try’s jobs.

55

In the US, the “Big Three” index funds,

Vanguards, BlackRock and State Street make up

96 % of the shareholdings of Fortune 250 compa-

nies and exercise signicant influence over share-

holder proposals, especially on proposals relat-

ed to the environment, social matters and govern-

ance.

56

This concentration of power, reinforced by

their capacity to organise lobbying and their strong

political networks, gives them tremendous lever-

age when it comes to public decision making.

57

The

resulting power imbalance between policymakers,

business and civil society hampers any progress

towards sustainable solutions.

58

Solutions

Options for systemic change

Drawing on the reviewed literature, we propose

several actions to overcome these barriers. Policy

actions can be grouped into three clusters: govern-

ance related issues, scal policy and growth inde-

pendence and power. We summarise key argu-

ments and invite readers to consult the sources

provided in the footnotes.

Multidimensional Indicators,

monitoring capacity, and legal

frameworks

Political decision-making should give equal

weight to the environment, wellbeing and eco-

nomic aspects in order to build ecological resil-

ience and social wellbeing. This requires develop-

ing and implementing policies that consider short-

as well as long-term environmental and social

impacts. To achieve this, governments should

replace purely economic measures as indicators

of progress that guide political decision-making,

such as Gross Domestic Product

59

– which does not

account for the negative environmental impacts

of economic growth, or the negative impacts on

26

Policy and governanceBuilding a resilient economy

Content ↑

human health and social relationships. A group

of countries, including New Zealand and Scotland,

are exploring alternatives using Wellbeing Budg-

ets which rely on a multidimensional set of indi-

cators.

60, 61

The alternatives are there.

62

What is

missing is their implementation and their actual

use in political decision-making processes.

Indicators are not only measurements but

can also determine accountability and effective-

ly change policy decisions, if they are incorporat-

ed into policy design and decision-making pro-

cesses. This would require methods, models and a

community of users able to understand and evalu-

ate the quantitative as well as qualitative impacts

of policies on wellbeing and the environment, as

exists for economic indicators.

63

Some argue that

such skills should be accompanied by training in

systems thinking, to build capacity in public insti-

tutions in understanding feedback mechanisms

between the economy, society, environment and

associated tipping points.

64, 65

Such indicators for

policies should also be used to assess existing sub-

sidies and tax systems, subjecting them to a critical

analysis of their domestic and international envi-

ronmental and social impacts.

66, 67, 68

Governance systems would need to be legal-

ly obligated to adopt long-term criteria to ensure

that an enhanced understanding of environmen-

tal, social and economic impacts and interlinkag-

es inform policies. The upcoming Environment Act

in the UK or the Climate Law in the EU are impor-

tant steps in securing obligations among poli-

cymakers to incorporate future factors and the

needs of nature into decision-making. Proposals

in the literature include the legal recognition of

the rights of nature, as in New Zealand, Bolivia or

Ecuador.

69

A new democratically elected chamber

with the responsibility of representing the inter-

ests of future generations could have veto power

on decisions with long-term impacts.

70

This would

increase pressure to nd solutions that mediate

conflicts between the present and future inter-

est groups. One important initiative in this vein is

the Wellbeing of Future Generations Act in Wales,

which requires public bodies to think about the

long-term impact of their decisions, in terms of

their effects on persistent problems such as pov-

erty, health inequalities and climate change, offer-

ing opportunities to bring about long-lasting, posi-

tive change for current and future generations.

Fiscal policy and growth

independence

However, for long-termism to be embedded in pol-

icy, another structural barrier must be overcome.

The puzzle of economic growth dependency needs

to be solved.

71, 72

The COVID-19 crisis has demon-

strated how steadfast public perception is that sta-

bility depends on economic growth. Placing social,

environmental and economic stability at the cen-

tre of concern is not merely a matter of political will.

Economies today seem to be structurally depend-

ent on the continuous expansion of the economy.

Becoming growth independent means nd-

ing other ways of generating employment, pro-

moting equality and reducing debt. It is not about

de-growing the economy. It is about recognising

the fundamental uncertainty regarding the future.

Due to the complexity and amount of assump-

tions involved, neither science nor policy can fore-

see how stronger environmental commitments and

regulation will affect aggregate economic growth

in the long-term. It would be great, if green growth

and technology solved the problem and ensured

that today's economies stayed within planetary

boundaries while growing. However, as outlined

recently in the Dasgupta Interim Report

73

, innova-

tion is likely to be too slow for addressing urgent

environmental challenges. Becoming growth inde-

pendent is about preparing for the possibility

that ecological resilience can only be maintained

through a steady-state economy or a decrease in

consumption and production. In addition, policy-

27

Policy and governanceBuilding a resilient economy

Content ↑

makers must rethink scal policy. A green trans-

formation requires substantial public invest-

ment. At the same time, it will be crucial to invest

where the economy creates real public use-val-

ue: health care, education, nursing care, public

parks and clean energy, transport and infrastruc-

ture.

74, 75

To do so, sufcient amounts of resources

must be available. Thereby, regulations such as the

Stability and Growth Pact in the EU, or the Char-

ter for Budget Responsibility in the UK dene how

much money can be spent and what it is spent for.

Changing the legislations that assess scal space

can create space for new investments.

These new investments can, for instance, be

directed by a Green Investment Bank

76

to where

they minimise ecological risks and maximise social

value. However, such investments often face high-

er debts. Charles Goodhart and Michael Hudson

therefore propose a modern form of debt jubi-

lees to deal with this challenge, where those forms

of debt most largely contributing to income and

wealth inequalities could be cancelled by funding

from a land or property tax.

77, 78

Additional resources can come from taxa-

tion on activities that produce damage instead

of value, and by ghting tax evasion and offshor-

ing. Legislation denes how much money is taxed

and who pays that money, thus guiding economic

development in a certain direction. More taxes can

be collected by reducing tax advantages for fossil

fuel industries

79, 80

or implementing taxes on activ-

ities that are harmful to the environment and the

public good (e. g. carbon taxes

81, 82

). Policy would

thereby internalise external effects from econom-

ic activities and incentivise the right kind of behav-

iour. Taxes can also come from skimming off eco-

nomic rents: increases in value that occur not by

the personal investment of people, but through the

investment of the State

83, 84

or are not associated

with real economic activities (e. g. a nancial trans-

action tax

85

).

Limiting power and

empowerment for change

Policymakers will face considerable resistance to

change, if policies are accompanied by concen-

trated impacts that run counter to the interests

of powerful actors. To prevent this, policies that

combat power inequalities are important. Often,

money results in political power (in the sense of an

individual’s or group’s ability to influence political

decision making), over the use of public resourc-

es and the implementation of policies

86

. Propos-

als to break these power imbalances by distribut-

ing money more equally range from redistributing

economic rents through land tax reforms

87

, pro-

gressive wealth and inheritance taxes

88

to struc-

tural approaches like business unbundling, strong-

er regulation for mergers to a change in owner-

ship structures as a whole

89, 90

, to maximum sizes

of companies

91

, income limits

92, 93

or basic income

schemes

94

.

Tackling power imbalances is not only about

limiting the power of influential actors, but also

about increasing power of less powerful groups.

One way to achieve this is to extend policy coher-

ence boundaries to non-state actors that operate

outside or across the borders of national legal regu-

lation.

95

This includes corporate norms and compli-

ance systems, new business models, new ways of

forming civil society groups, the use of social media,

etc. Policy coherence needs new means of govern-

ance. New forms of collaboration between poli-

cy and the private as well as the civil society sec-

tor can promote policies that cut across functional

boundaries to create solutions that anticipate soci-

etal and global dependencies. Citizen assemblies

can become a new form of policy design and inno-

vation.

96

28

FinanceBuilding a resilient economy

Content ↑

The vast majority of nancial institutions fail to

integrate environmental and long-term factors

into their decision making. This leads to a large

misallocation of funds. On the one hand, funding the

transition to a sustainable economy is estimated to

cost between US $ 5–7 trillion per year until 2030.

However, public and private nance only mobilis-

es US $ 2.5 trillion, leaving a signicant shortfall of

funds

97, 98

. On the other hand, nancial institutions

continue to fund unsustainable economic activities.

Bond and equity markets are, for instance, overex-

posed to fossil fuel intensive and polluting sectors.

This means that a large amount of capital is being

invested in environmentally harmful business, rath-

er than sustainable alternatives. Notably, this also

applies to the seemingly “market neutral” asset

purchasing programs of central banks

99

. A similar

dynamic exists in bank-based nance. It has been

estimated that banks across the world have invest-

ed a total of US $ 2.7 trillion in fossil fuel projects

and companies between 2016 and 2019; after the

signing of the Paris Agreement

100

. Of this amount,

UK banks alone accounted for US $ 100 billion

between 2016 and 2018

101

. In addition, the high

exposure of the UK’s nancial sector to mortgages

on real estate with low energy efciency illustrates

how urgently the nancial system needs reform, if

it is to become an enabler rather than a barrier to

environmental sustainability

102

.

This collective misallocation of funding has

enormous implications in the way of destabilis-

ing the planet’s environmental systems. Since

economic and nancial systems are embedded

in earth systems, nancial stability itself is at risk.

Now realising the systemic risks for nancial sta-

bility that arise from climate change, which are

estimated at US $ 43 trillion in nancial losses by

2100

103

, regulators and central banks have start-

ed to explore and integrate climate-related risks

into their work.

Climate-related risks are, however, not the only

concern for nance. A WWF sponsored study has

recently estimated potential losses from ongoing

biodiversity-related loss at a minimum of US $ 10

trillion by 2050

104

. Another study sponsored by

UNEP suggests these risks are heavily concentrat-

ed in a few sectors, including agriculture, apparel

and resource extraction and use

105

.

Notably, such high-level scenarios are likely to

underestimate the real risks that materialise. They

are based on assumptions about highly interde-

pendent and uncertain environmental, technolog-

ical and political trajectories. In light of this, recent

working papers from the Bank for International Set-

tlements

106

and the UCL’s Institute for Innovation

and Public Purpose

107

have pointed out the limita-

tions of relying on modelling. Citing the precaution-

ary principle and the fundamental uncertainty that

comes with changes to the planet’s natural sys-

tems, the authors advocate rapid and transform-

ative action to avoid potentially catastrophic out-

comes for nature, the economy and nance.

Financial institutions and their supervisors

need to better incorporate environmental criteria

into their allocative decision making and their risk

assessments. Ethical investors, ESG rating agen-

cies and NGOs have pioneered the work on dis-

closing and understanding the data on how nance

contributes to and is exposed to environmental

risks. Most recently, initiatives like the FSB TCFD

have added much-needed rigorousness and scope

to these assessments. Nonetheless, disclosure

alone remains insufcient if nancial institutions

are unable or unwilling to process it.

108

This needs

to go further by making sure that this data is used

Finance

» The collective misallocation

of private funding has enormous

implications in the way of

destabilising the planet’s

environmental systems.«

29

FinanceBuilding a resilient economy

Content ↑

effectively. The priorities and mandates of regu-

lators need to change. Additionally, actors across

the nancial system including nancial institutions,

regulators and service providers (e. g. rating agen-

cies, index providers) need to develop common

metrics and methodologies that make the relevant

environmental issues clear. Together, these shifts

could give rise to policies and investment practic-

es that better allocate funding.

Challenges

Barriers to a sustainable trans-

formation of the nancial system

There are, however, institutional and legal reasons

for the misallocation of funds and the failure to

take environmental issues into account.

Short-termism

The rst issue is that nancial institutions and their

regulators often only operate using a time horizon

of one business cycle, and thus, only look at what

happens in the next one to ve years

109, 110

. In addi-

tion, the practice of quarterly reporting has been

linked to short-termism by some observers

111

. The

associated longer-term environmental impacts and

risks of nancial transactions are often not consid-

ered and therefore not appropriately priced.

A second issue is that large nancial institu-

tions and investors are generally risk averse when

it comes to economic risks. This is because regu-

lation and mandates require that they do not gam-

ble with the contributions of pension savers or

insurance holders. While this is a sensible policy,

it also means that such nancial institutions dis-

play a status quo bias, which means that they are

greatly exposed to the current unsustainable econ-

omy, whereas alternative (possibly more sustain-

able, but less protable) businesses face a short-

age or increased cost of funding. This status quo

bias is further exacerbated by the use of indices

like the S & P 500 or the MSCI World as proxies for

“the market” against which risks and returns are

benchmarked. Such indices have been found to be

biased in favour of the fossil fuel industry and to

grant undue infrastructural power to index provid-

ers like MSCI, which make far-reaching decisions

about capital allocations.

112, 113

The inability of institutional investors to fund

sustainable projects is further exacerbated by

narrow legal interpretations of their responsibil-

ities (i. e. duciary duties). These postulate that

they need only take short-term prot maximisa-

tion into account

114

. A nal institutional issue is

the mismatch of scale across capital markets in

particular. Impactful environmental preservation

projects often have a volume of less than one mil-

lion euro or dollars, while the average green bond

requires a volume of 100 million EUR.

115

Lack of metrics

A second cluster of barriers concerns the lack of

common metrics for environmental and broader

sustainability indicators. While data and ratings

on Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG)

criteria abound, different methodologies make

standardisation and comparison difcult. The lack

of correlation between different providers has led

critics to adopt the term “alphabet soup” when

referring to ESG

116, 117, 118

. Some of the confusion of

ESG methodologies comes from the fact that data

providers often assess companies’ targets and pol-

icies instead of the actual environmental and social

outcomes. Initiatives like the EU’s upcoming green

taxonomy and the Task Force on Climate-relat-

ed Financial Disclosures (TCFD), as well as more

established frameworks such as the Global Report-

ing Initiative or the CDP (formerly Carbon Disclo-

sure Project), aim to enhance the clarity of envi-

30

FinanceBuilding a resilient economy

Content ↑

ronment-related information. Most recently, sev-

eral organisations including the WWF and UNEP

launched the Taskforce for Nature-related Finan-

cial Disclosures

119

. Given increased deteriora-

tion of ecosystems and increased awareness of

nance and the economy’s dependence on natu-

ral systems

120

, this task force aims to improve the

reporting, metrics and data that nancial institu-

tions need in order to better understand their risks,

dependencies and impacts on nature by 2022.

These developments notwithstanding, the lack

of agreed upon and widely used metrics allows

nancial institutions to engage in “greenwashing”,

i. e. selecting the ESG measures that make their

portfolio look sustainable. This kind of ESG data

shopping, however, defeats the purpose of sustain-

able investment, since instead of reallocating cap-

ital towards sustainable businesses and projects,

existing assets are merely relabelled. In addition,

the “noise” that such competing methods gener-

ates, makes it harder to clearly identify the long-

term risks.

Culture and Policy Frameworks

Thirdly, there are barriers to sustainability in

nance that are related to but not completely cov-

ered in the institutional and legal barriers, which

we term culture and policy frameworks.

Financial practitioners tend to reflect little on

long-term and environmental impacts in nance

education and in the work environment. Instead,

short-termism and a narrow conception of mone-

tary prot are prioritised. This is reinforced by the

dominant metrics and tools that nancial prac-

titioners use. The ubiquity of narrow Cost Bene-

t Analysis and short-term nancial pricing mod-

els like the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) as

well as Modern Portfolio Theory more generally, are

prime examples of this dynamic.

A second broader issue is the overall policy

framework beyond the regulation of the nancial

sector (see Chapter 1). The materialisation of the

risks for unsustainable investments depends ulti-

mately on real economy policies. If, for instance, a

high carbon tax is implemented or internal com-

bustion engines are prohibited, this represents

a risk for those who currently invest in nancial

assets linked to these economic activities – in the

literature, this issue is denoted by the concepts

of stranded assets and transition risks. If, howev-

er, nancial institutions do not believe that gov-

ernments will act forcefully, they have little incen-

tive to already factor in such transition risks today.

121

For this reason, focusing on risk disclosures in

nance only is unlikely to shift allocation patterns.

On the other hand, the point about the signi-

cance of real economy policies should not be over-

stated. Finance is not merely a reflection of the real

economy and reforms to the nancial system are

not only second-best strategies. Instead, there is

a two-way dynamic between nance and the real

economy. The nancial system processes informa-

tion from the real economy according to its own

institutional dynamics. Allocation decisions that

are made in this process not only reflect the cur-

rent real economy, but also contribute to the con-

struction of the future real economy.

122, 123

As such,

reforms of both the real economy and the nan-

cial system are needed to transition to a sustain-

able economy.

Solutions

The role of policy in setting

nance on course for tackling

today’s challenges

Institutional legacies, mandates and legal inter-

pretations are the outcomes of past political

choices and policies. Likewise, what is considered

today as standardised and “hard” nancial data is,

31

FinanceBuilding a resilient economy

Content ↑

in fact, the outcome of legal and political process-

es

124

. The barriers to nance adopting and playing

its part in funding a sustainable transition is there-

fore not set in stone, and policymakers can rewrite

the rules of the game according to the altered pri-

orities that planetary emergencies demand. We

have identied two main clusters where policy can

intervene.

Mandates and legal

interpretations

In its simplest form, a mandate describes the

objectives of a public institution. Accordingly, a

body with political legitimacy like the UK Parliament

delegates the task of achieving certain goals to an

independent public body like the Bank of England

(BoE). In the context of nance, central banks and

regulators are the public institutions whose man-

dates are especially relevant. Mandates serve on the

one hand to ensure the consistency of policies pre-

scribed by regulators and central banks, since they

prevent politicians from creating confusion by con-

stantly adjusting policies. On the other hand, man-

dates prevent “mission creep” on the part of these

institutions by clearly circumscribing their tasks.

Nonetheless, it is important to remember that

mandates remain based on political decisions and

that they reflect the context of those decisions. A

recent review of 135 central banks nds that only

13 % out of the reviewed institutions have a sus-

tainability-related mandate

125

. Some, like the BoE,

have a broader mandate that tasks them with con-

tributing to the government’s priorities. However,

due to different political priorities in the past, many

central banks, including the BoE, are still primari-

ly tasked with ensuring price stability (and more

recently nancial stability). This could make them

a target for criticisms of mission creep, should they

try to address environmental issues like climate

change

126

.

Legal interpretations, on the other hand, deter-

mine the meaning and implications of a concept in

regulation or any other piece of legislation. Such

clarication determines, for example, whether and

to what degree the task of maintaining nancial

stability forces central banks to address climate

change. Yet legal interpretations also impact private

nancial actors. For instance, the question of which

risks can be considered “nancially material” influ-

ences the reporting and risk assessments of nan-

cial institutions. Another example is the above-men-

tioned concept of duciary duty, which has implica-

tions for the allocation strategies of institutions like

pension funds. The list below outlines certain poli-

cies that could modify the cluster of mandates and

legal interpretations towards sustainability:

• Democratic consultation on the purpose of the

nancial sector led by the Parliament, whose

outputs would be used to update the mandates