Matt Marx

POLICY PROPOSAL 2018-04 | FEBRUARY 2018

Reforming Non-Competes to Support Workers

The Hamilton Project seeks to advance America’s promise

of opportunity, prosperity, and growth.

We believe that today’s increasingly competitive global economy

demands public policy ideas commensurate with the challenges

of the 21st Century. The Project’s economic strategy reflects a

judgment that long-term prosperity is best achieved by fostering

economic growth and broad participation in that growth, by

enhancing individual economic security, and by embracing a role

for effective government in making needed public investments.

Our strategy calls for combining public investment, a secure social

safety net, and fiscal discipline. In that framework, the Project

puts forward innovative proposals from leading economic thinkers

— based on credible evidence and experience, not ideology or

doctrine — to introduce new and effective policy options into the

national debate.

The Project is named after Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s

first Treasury Secretary, who laid the foundation for the modern

American economy. Hamilton stood for sound fiscal policy,

believed that broad-based opportunity for advancement would

drive American economic growth, and recognized that “prudent

aids and encouragements on the part of government” are

necessary to enhance and guide market forces. The guiding

principles of the Project remain consistent with these views.

MISSION STATEMENT

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 1

Reforming Non-Competes to Support Workers

Matt Marx

Boston University

is policy proposal is a proposal from the author(s). As emphasized in e Hamilton Project’s original

strategy paper, the Project was designed in part to provide a forum for leading thinkers across the nation to

put forward innovative and potentially important economic policy ideas that share the Project’s broad goals

of promoting economic growth, broad-based participation in growth, and economic security. e author(s)

are invited to express their own ideas in policy papers, whether or not the Project’s sta or advisory council

agrees with the specic proposals. is policy paper is oered in that spirit.

FEBRUARY 2018

2 Reforming Non-Competes to Support Workers

Abstract

is report describes evidence from empirical research on non-compete agreements and recommends policies to balance the interests

of rms and workers. Firms use non-competes widely in order to minimize recruiting costs, safeguard investments, and protect

intellectual property more easily than is achieved via non-disclosure agreements. But these benets come at a cost to workers, whose

career exibility is compromised—oen without their informed consent.

4 Reforming Non-Competes to Support Workers

Introduction

T

he American Industrial Revolution arguably saw its

inception in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, at the Slater Mill

on the Blackstone River. is was the rst place in the

New World where cotton was spun into thread by machine.

Samuel Slater, founder of the eponymous mill, had emigrated

from England where he had worked on the Arkwright spinning

machine (Simonds 1990). However, Slater’s homeland had

taken steps to prevent him from developing his business in the

United States.

Among the reasons underlying England’s rapid rise to

industrial power was its aggressive policy of recruiting skilled

laborers by granting national monopolies (i.e., an exclusive

right to produce goods using a particular technology) to those

who pirated technologies from other countries (Ben-Atar

2004). At the same time, England adopted restrictions that

forbade skilled artisans—including those who had imported

stolen technologies—from leaving the country. Essentially,

Samuel Slater was subject to a ban on leaving the country

to practice his profession in any other country: he was not

allowed to compete against England. Fortunately for Slater,

his slight stature enabled him to disguise himself as a young

farm boy and slip past emigration controllers in 1789 to board

a ship for the New World.

Although revered in the United States as the father of the

American Industrial Revolution, Slater is oen referred to in

the United Kingdom as Slater the Traitor for having purloined

British textile technology. Had England’s restrictions

successfully bound him to his home country, the American

Industrial Revolution would surely have been delayed. e

Slater story highlights several controversial aspects of laws that

seek to prevent workers from leaving their current workplace

to take their expertise elsewhere. Almost certainly, Slater

would have led a less distinguished career if he had remained

bound by England’s prohibition against the departure of

skilled artisans. Moreover, it seems that America’s gain was

England’s loss.

When considering the state enforcement of barriers to the

mobility of skilled workers, similar trade-os apply today

between the interests of workers, incumbent rms, and new

or even not-yet-founded rms. e balance between these

interests is not straightforward, which could explain why,

at least in the United States, states have taken very dierent

approaches regarding post-employment covenants not to

compete (hereaer, non-competes).

WHAT ARE NON-COMPETES AND HOW OFTEN ARE

THEY USED?

A non-compete is a section of an employment contract in

which the worker pledges not to join or found a rival company

for a certain period of time aer leaving the company. e use

of non-competes dates back to 1414, when a former apprentice

was sued for having set up shop in the same city despite having

promised not to do so aer his training was complete. e

judge in the case is said to have not only thrown out the lawsuit

but also to have threatened the plainti with jail time. e

recent decimation by bubonic plague of the northern England

labor supply had motivated the passage of the Ordinance of

Labourers, which essentially outlawed unemployment for the

able-bodied (Marx and Fleming 2012). However, this legal

approach did not last in most jurisdictions, and today non-

competes are widely used in a variety of industries.

Non-compete agreements between employers and their

employees limit workers’ labor market opportunities

aer leaving a rm. Although the details of non-compete

contracts—as well as their enforceability under state law—

vary considerably, they generally prohibit exiting workers

from either joining or founding a business that competes with

the previous employer. is prohibition is time-limited, and

is typically also limited by region and industry, though the

scope of the contract is sometimes quite broad.

In an increasingly knowledge-based economy, the most

important assets of rms are not property, plant, and

equipment. Rather, they are lodged in the minds of workers

who walk out the door every night. Firms must either win or

force workers’ loyalty, lest they incur the time and costs of

replacing those workers. Moreover, ex-employees who found

or join a rival rm pose additional problems for their former

employer. If the former employer has in eect prescreened

qualied workers who are then poached by rivals, those rivals

have lowered the cost and risk of their own recruitment. To

the extent that the former employer increased those workers’

value by investing in their training, that investment is lost.

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 5

And if the ex-employee were granted access to condential

information, this information could leak to the new employer.

Today, non-competes are widely used in a variety of

occupations, especially among knowledge workers and

executives. Prescott, Bishara, and Starr (2016) estimate

that 18 percent of respondents to an online survey across a

broad set of occupations had signed a non-compete for their

current job. Looking specically at engineers, Marx (2011)

nds that 43 percent of workers had signed a non-compete

in the past 10 years. Executives were even more likely to have

signed: Garmaise (2011) nds that at least 70 percent of senior

executives in public companies were bound by a non-compete.

THE CHILLING EFFECT

Another way to study the role of non-competes is to count

lawsuits. If one assumes that non-competes are meaningful

only insofar as employers seek injunctive relief against ex-

employees, then counts of lawsuits ought to be a useful metric

for understanding their impact. Jay Shepherd of the Shepherd

Law Group reports that there were 1,017 published non-

compete decisions in 2009 (Shepherd 2010). e Bureau of

Labor Statistics (BLS) reported that there were 154,142,000

workers in the United States in that same year (BLS 2009).

If the eect of non-competes were limited to the courtroom,

simple math would suggest that 0.0007 percent of workers

were aected by non-competes, according to this denition.

Given the high fraction of workers who are asked to sign non-

competes, the eect of these contracts is unlikely to be limited

to judicial proceedings alone.

Rather, non-competes exert a chilling eect on workers even

in the absence of a lawsuit. None of the interviewees in Marx’s

(2011) study who altered their career direction due to a non-

compete were sued. Some received threatening letters or phone

calls from their ex-employers, however, including one woman

whose former boss called her for months to ask where she was

working. Others, even if they were not directly threatened,

assumed that if they were sued, they would lose due to the expense

of defending themselves. Additional evidence for a chilling

eect can be found in the estimate from Prescott, Bishara, and

Starr (2016) that non-compete agreements are signed at roughly

the same rate in the few states where they are unenforceable as

in states where they can be upheld in court. Although part of

this pattern could be an artifact of standardized, nationwide

human resource policies whereby multistate rms require every

employee in any state to sign, it is also possible that single-state

rms hope to capitalize on the chilling eect for their employees

who are unaware of state policy.

SUMMARY OF POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

e benets of non-competes accrue primarily to employers

and at the expense of employees. Moreover, the process by

which these parties agree to such contracts only rarely includes

a true negotiation. Rather, employees are routinely strong-

armed into signing the contract without carefully considering

its implications, suggesting ve avenues for reform:

1. End abusive practices including ambushing employees

by not informing them about the requirement to sign a

non-compete until aer they have accepted the job oer

and possibly turned down other oers, thus losing their

negotiation leverage.

2. End the widespread practice whereby rms are not

required to compensate existing employees in any way for

signing a new or revised non-compete. (Rather, continued

employment is said to be sucient consideration for the

requirement to sign.) Workers should have the right to

refuse to sign an updated contract without retaliation.

3. End the non-compete enforcement practice whereby, rather

than rule that a non-compete is valid or invalid according

to state law, a judge can rewrite an overbroad or egregious

contract to bring it in line with state guidelines.

4. Empower state attorneys general via unfair-employment-

practice statutes to obtain settlements with rms that

require workers to sign predatory, unenforceable non-

competes. is is particularly important given that much of

the impact of non-competes is attributable not to lawsuits

but instead to the chilling eect of both enforceable and

unenforceable contracts.

5. Institute mechanisms to make non-disclosure agreements

(NDAs) easier to enforce, allowing them to better substitute

for non-competes.

6 Reforming Non-Competes to Support Workers

The Challenge

EVIDENCE ON THE ANTECEDENTS AND

CONSEQUENCES OF NON-COMPETE AGREEMENTS

Although legal scholars have discussed the potential impacts

of post-employment covenants not to compete, empirical work

on the impacts of non-competes has been scarce until recently.

In the past een years several scholars have attempted to link

non-competes to outcomes for workers, rms, and regions.

Much of this work falls into two general categories:

1. Surveys that collect data on workers who have signed non-

competes. ese surveys oer insight into the prevalence

of non-competes and the process by which employers get

employees to sign them. Some studies take an additional step

by providing correlations between presence of a non-compete

and other outcomes of interest, although this analysis

cannot identify the causal impact of non-competes on such

outcomes. But an understanding of how non-competes are

used is critical to assessing their costs and benets, including

implications of non-competes for the careers of individual

workers and their eects on businesses.

2. Analyses based on state-level dierences in whether and

how non-competes are enforceable. ese studies typically

leverage changes over time in laws or court decisions. ey

do not incorporate survey data on who has or has not

signed an agreement, data that are currently only available

at a single point in time. However, these studies can help

answer questions about the likely consequences of state

policy reforms, including eects on regional productivity,

entrepreneurship, and economic growth.

ese types of studies have been conducted in four general

areas. First, how and how oen are non-competes used and

among which types of employees; moreover, what is the

process by which employee signatures are obtained? Second,

what are the implications of non-competes for individual

careers? ird, do rms benet from non-competes? Fourth,

and abstracting from employers and employees, what are

the more general implications of non-competes for regional

productivity, entrepreneurship, and economic growth?

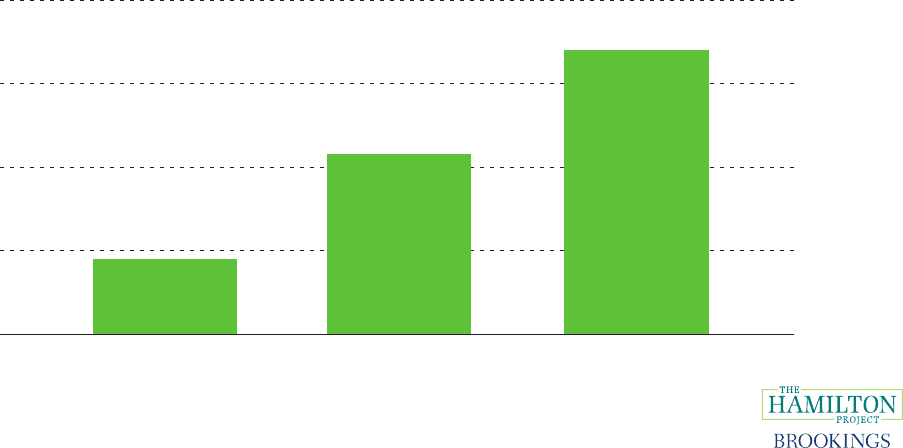

Source: Marx 2011.

Note: Results are from a survey of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers with 1,029 respondents.

FIGURE 1.

Share of Non-Compete Agreements, by Duration

Percent of non-competes

Less than 1 year Between 1 and 2 years Between 2 and 5 years Greater than 5 years

0

20

40

60

80

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 7

PREVALENCE AND PROCESS

Four papers have gathered data regarding the prevalence of

non-compete agreements. First, Schwab and omas (2006)

reviewed employment contracts from 865 respondents to a

survey of chief executive ocers (CEOs) from the S&P 500,

S&P MidCap 400, and S&P SmallCap 600. Of those executives,

67.5 percent of respondents had a non-compete. e majority of

those agreements were two years in duration (31.5 percent); 21.3

percent of them were one year. ese results closely parallel the

70.2 percent rate of non-competes in the employment contracts

of Execucomp executives found by Garmaise (2011).

Of course, CEOs represent only a tiny segment of the labor

market and are moreover a unique subset of employees. Marx

(2011) conducted a broader survey of the Institute of Electrical

and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), with 1,029 of 5,000

randomly selected members responding. Of these engineers

working in several industries, 43.3 percent said that they had

signed a non-compete within the past 10 years. Most survey

respondents indicated that their non-compete lasted no

longer than one year, but more than one-third of respondents

claimed that the non-compete they signed was longer than

one year (see gure 1).

ough more numerous than CEOs, engineers also constitute

a small, highly educated segment of the labor market. In

2014 Prescott, Bishara, and Starr (2016) conducted an online

survey of more than 700,000 people registered to ll out

online surveys. eir 1.5 percent response rate yielded 11,505

responses. Approximately 15 percent of respondents replied

that they were currently subject to a non-compete, and it

is estimated that an additional 3 percent of respondents

who were not sure whether they had signed a non-compete

probably had, for a total of 18 percent of all workers. During

their entire career, 43 percent said that they had signed one,

similar to the result in Marx’s survey, but for a much wider

variety of occupations. ese estimates are shown in gure 2.

For those workers who are bound by non-competes, the process

by which employers obtain signatures from employees is

potentially very important. One key nding is that this process

bears little resemblance to “negotiat[ing] contracts of mutual

benet,” as some have sought to portray it (Regan 2014). In

Marx’s (2011) survey of engineers, more than two-thirds of

respondents who signed a non-compete (69.5 percent) reported

that the request for them to sign a non-compete came aer the

oer letter. Note that aer accepting an oer of employment

(and turning down other oers, if any), the new hire loses

negotiating leverage. Nearly one-quarter of respondents (24.5

percent) were asked to sign the non-compete on their rst day

at work (see gure 3). e lack of notice contributes to the fact

that only one in ten (12.6 percent) of those who signed a non-

compete sought legal advice before doing so; in fact, fewer

than one in twenty (4.6 percent) of those who signed the non-

compete on their rst day of work sought legal advice. Of those

who did not seek legal advice, nearly half reported that they felt

time pressure to sign or that they were told the non-compete

was nonnegotiable.

FIGURE 2.

Share of Workers with a Non-Compete Agreement, Selected Occupations

Source: Marx 2011; Prescott, Bishara, and Starr 2016; Schwab and Thomas 2006.

Percent of workers with a non-compete

All occupations Engineers Executives of

public companies

0

20

40

60

80

8 Reforming Non-Competes to Support Workers

e disadvantages to workers during the signing process are

exacerbated for those who are younger or less experienced.

Younger workers are less than one-third as likely as their

more-experienced counterparts to seek legal advice on their

non-compete, perhaps due in part to the fact that they receive

a non-compete with a job oer even less oen than more-

senior colleagues. ey are less than half as likely to refuse to

sign a non-compete, whether measured by age (11.2 percent

of older workers refuse, compared with only 3.7 percent of

younger workers) or years of experience (10.4 percent of more-

experienced workers versus 5.0 percent of less-experienced

workers).

WORKERS

Non-competes are common and the circumstances of their

signing are oen troubling. What eects do these non-

competes have on workers? ree important questions include

how non-competes aect mobility, wages, and on-the-job

motivation.

Mobility

Perhaps the most well-established eect in the non-compete

literature is that such employment agreements discourage

workers from changing jobs. Fallick, Fleischman, and Rebitzer

(2006) were the rst to show suggestive evidence along these

lines: they found much higher levels of job mobility among

workers in the California computing industry. at said, the

authors were careful to note that the correlations they noticed

might be explained instead by dierences in culture or other

factors between California and other states. Other scholars

have built on this work by exploiting state-level changes in

non-compete policy—looking at the same places over time—to

identify the causal eects of non-competes and non-compete

enforceability on job-hopping.

Marx, Strumsky, and Fleming (2009) leverage an inadvertent

change in Michigan’s non-compete policy, showing that

Michigan’s unexpected switch from a California-style ban

to allowing non-compete enforcement resulted in a drop in

job mobility of 8.1 percent. Moreover, this result is not driven

by Michigan’s large automotive industry. Furthermore, non-

competes have dierential eects on workers, with larger

impacts on those who have specialized skills.

Garmaise (2011) also nds non-competes to be a brake on

mobility. He takes advantage of non-compete policy reversals

in Florida, Louisiana, and Texas to show that executives at

large, publicly traded corporations are materially less likely

to change jobs when those states tighten enforcement of non-

competes. When they do change jobs, moreover, they are more

likely to move to a dierent industry.

Marx (2011) also nds evidence of such career detours among

52 randomly sampled interviewees in the speech recognition

industry. During these career detours, interviewees reported

lower compensation because they were unable to use some of

their skills. One worker observed that the non-compete was

particularly damaging to her because it precluded use not only

of training from the rm where she signed the agreement,

but also of all her prior relevant expertise: “I’ve been in this

industry for 20 years. I have a PhD in the eld. I walked in

the door with an enormous amount of experience, and while

I worked there for a year in a half they added maybe, what, 2

percent to that? And now they want to prevent me from using

any of what I know?” (Marx 2011, 705).

To some extent, the ndings regarding non-competes and

mobility are unsurprising. If employers are asking employees to

covenant not to join a rival aer leaving the rm, the two principal

implications of that request are that workers change jobs less oen

Source: Marx 2011.

Note: Results are from a survey of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers with 1,029 respondents and restricted to workers who have signed a

non-compete agreement.

FIGURE 3.

Share of Non-Compete Agreements, by Time of Signing

Percent of non-competes

0 20 40 60 80 100

With oer

After oer,

before starting

First day of work After starting

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 9

and, when they do, they tend to go to non-rivals. However, if one

were to assume that non-competes have their impact primarily

via lawsuits, the results are surprising: with only a small number

of non-compete lawsuits, the observed mobility impact of non-

competes should not occur. is observation reinforces the view

that a non-compete chilling eect is important.

Wages

If non-compete agreements discourage workers from changing

jobs, this restriction circumscribes the eective market for their

skills. With fewer rms to bid for their labor, they might receive

fewer and less-attractive job oers. Although workers bound by

non-competes could be more valuable to their employer than

other workers, whether their employer rewards them for that

increased value might depend on the existence and credibility

of external oers from other companies. Captive employees

with limited outside options—even those with high value to

their employers—might be paid less than others.

To date, the only published paper to investigate the impact of

non-compete agreements on wages is Garmaise (2011). He nds

that executives are paid less in states that have adopted stricter

non-compete policies. Garmaise compares compensation in

Florida, Louisiana, and Texas before and aer non-compete

policies were changed. Unfortunately, the literature currently

has less evidence to oer on the impact of non-competes on

the wages of lower-ranked employees. Although it would seem

that similar arguments should apply to those who do not hold

executive positions—perhaps more strongly, in fact—this is a

topic of ongoing investigation.

Motivation

If non-compete agreements constrain mobility and wages—

and if they do not provide clear benets for workers—one

might wonder whether such contracts adversely aect

employee performance and/or motivation. at said, the

potential eect is ambiguous. On the one hand, employees might

be demoralized by the constraint represented by non-competes. On

the other, if their only job option using their current skillset is with

their existing employer, they could be highly motivated to perform

well and avoid termination (especially because some non-compete

agreements continue to bind workers who are red).

ese opposing eects might help to explain the results of Buenstorf

et al. (2016). Recognizing that it is dicult to obtain data on employee

motivation, they instead conduct a laboratory experiment in which

two subjects are told that one will employ the other to work on an

uncertain innovation project. In one treatment, the worker is not

allowed to quit and take his or her skills to another rm; in the control,

the worker is allowed to move to another rm. e experiment

yields no dierence in eort between the treatment and control,

perhaps suggesting that non-competes do not inuence workplace

motivation. Of course, there could be substantial dierences between

the laboratory setting and the workplace.

FIRMS

Given the deleterious eects of non-competes on workers, it might

follow that rms benet from non-competes. Two papers indicate

that this is the case. First, Younge and Marx (2016) examine how

non-competes aect Tobin’s q (i.e., the market value of assets

divided by their replacement cost). ey nd that, compared to

states where non-compete laws did not change, the ability to block

employee mobility increased Tobin’s q by 9.75 percent aer Michigan

abandoned its ban on non-compete agreements. e eect is larger

in more highly competitive industries and is somewhat attenuated

by patent protection.

Conti (2014) also nds that rms can prot from non-competes, as

measured by the ability to pursue riskier research and development

(R&D) projects. He nds that a 1996 tightening of non-compete

laws in Florida increased both positive and negative extreme R&D

outcomes (dened as patents with either zero forward citations or

patents with citations in the top 1 percent), whereas the loosening of

non-compete laws in Texas during 1994 decreased extreme outcomes.

Moreover, the ability to retain sta and pay them less, as described

in the previous section, also benets rms. One might claim that it is

dicult to operate a business and invest in R&D without employee non-

compete agreements, yet one need look no further than California’s

Silicon Valley or San Diego biotech cluster for counterexamples to

the notion that a thriving innovation system cannot exist without

non-competes. If non-competes were truly essential to R&D, one

would have long since expected an exodus of technology rms from

California. Furthermore, some of the most vigorous opponents of

non-compete reform maintain extensive operations in California

(Borchers 2014). us, although non-compete agreements may confer

an advantage to existing rms, it certainly cannot be said that they are

essential to the operation of rms.

REGIONS

Non-competes might have important implications for overall

regional development, in addition to their eects on worker and

rm outcomes. Key regional considerations include the ow of

knowledge and talent as well as entrepreneurial activity. ese

channels potentially allow for substantial non-compete eects

on overall economic growth.

Flows of Knowledge and Talent

As previously discussed, talent ows less within states with

tighter non-compete laws. Researchers have also examined

labor ows across states. Marx, Singh, and Fleming (2015)

nd that Michigan’s rule change providing for enforcement

of non-compete agreements resulted in a brain drain of talent

out of the state. Specically, technical workers le for other

states with less-strict enforcement of non-competes.

1

Worse,

this brain drain due to non-compete agreements is greater for

the most highly skilled workers.

To the degree that knowledge is not always codied (as in a

patent), but oen resides in the minds of workers, it follows

that circumscribed mobility of workers might likewise

impede the ow of knowledge. Belenzon and Schankerman

10 Reforming Non-Competes to Support Workers

(2013) analyze the diusion of knowledge from the academy

to industry, examining citations to both university patents

and also to academic papers. Although their primary nding

is that the diusion of academic discoveries is constrained

by state borders, they nd that this is especially true in states

that have tighter non-compete laws. is suggests that non-

compete agreements may hamper the ow of information.

Although the restricted ow of talent and information likely

serves the interests of existing rms, throttling information

ow could have negative externalities for entrepreneurs and

a negative impact on overall economic performance. For

example, as discussed in the next section, it might be more

dicult for business start-ups to emerge and succeed.

Entrepreneurship

Non-competes act as a brake on entrepreneurial activity,

both by blocking the emergence of new companies and by

making it harder for them to grow. To the former point, Stuart

and Sorenson (2003) show that the spawning of new start-

ups following events like IPOs or acquisitions is attenuated

where non-competes are enforceable. Samila and Sorenson

(2011) follow up this study to show that a dollar of venture

capital goes further in creating start-ups, patents, and jobs

when spent in states that do not strictly enforce non-compete

agreements. Venture capital creates two to three times as much

growth in regions where non-competes are unenforceable.

eir nding is not just a Silicon Valley eect, but also holds

when Silicon Valley is excluded entirely from the analysis.

Starr, Balasubramanian, and Sakakibara (2017) likewise nd

that non-competes act as a brake on entrepreneurial entry,

although this eect is limited to intra-industry spin-os in

which employees of one company leave to found a rival in

the same industry. Workers founding start-ups in dierent

industries are unaected.

Non-competes not only make it more dicult to start a

company, but also make it harder to grow a start-up. Once the

company is incorporated, the founders must hire employees

with relevant skills to expand the business. Unless sucient

workers can be found among fresh college graduates or the

unemployed, existing rms are a primary source of potential

hires—especially for rms with specic expertise needs. Yet

start-ups could nd themselves at a disadvantage in labor

markets where non-competes are prevalent, both because

they might lack the legal and nancial resources to defend

themselves and also because potential hires’ mobility could

be chilled by non-competes they have signed. One of the

randomly selected interviewees with a non-compete in Marx’s

(2011) article stated that they were unlikely to accept a job

oer at a small rm: “I consciously excluded small companies

because I felt I couldn’t burden them with the risk of being

sued. [ey] wouldn’t necessarily be able to survive the lawsuit

whereas a larger company would.”

Ewens and Marx (2017) show the deleterious eect of non-

competes on start-up performance. Investigating venture-

capital-backed start-ups founded from 1995 through 2008 and

tracking their performance through the rst quarter of 2017,

they nd that the success of start-up companies oen requires

the hiring of new executives. Although some founders remain

as the CEO for decades, in many cases founders are seen

as incapable of leading the company as it scales beyond the

start-up phase. Enforceable non-compete agreements make

it more dicult to nd replacement executives with relevant

talent, which limits venture-capital-backed start-ups’ ability

to succeed.

Interestingly, there is one respect in which non-competes can

facilitate the market for start-up acquisition. Younge, Tong, and

Fleming (2015) show that acquisition activity was accelerated

in Michigan aer non-compete laws tightened. ey credit this

eect to the ability of acquiring rms to count on employees of

the target rm to stay on, given that employment contracts are

typically (but not always) acquired along with the purchase of

the rm. If this eect on acquisitions also applies to smaller

companies—which were not examined in this research—then

non-competes might help start-ups through this channel.

Given these ndings, it is not dicult to see why established

companies generally implement non-competes when they

are allowed to do so. Non-competes make it easier to retain

employees and to pay them less, and they reduce the threat

from new entrants within the industry. Moreover, when

acquiring start-ups incumbent rms more easily hold on

to talent. Yet these benets to rms come at the expense of

workers and start-ups.

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 11

A New Approach

T

he debate over employee non-compete agreements oen

centers around whether and how such contracts should

be enforced. A starting point for these discussions is oen

California’s longstanding refusal to enforce non-competes, based

on its Business and Professions Code 16600: “Every contract by

which anyone is restrained from engaging in a lawful profession,

trade, or business of any kind is to that extent void” (Gilson 1999,

616). Michigan’s Public Act 321 of 1905 instituted an enforcement

regime similar to California’s, which endured until March of

1985, when the state’s policy became more aligned with most

other states. Hawaii adopted a California-style policy in 2015 for

the information technology industry, rendering non-competes

unenforceable for that sector. Table 1 summarizes recent changes

in state law.

Determining the ideal enforcement policy is hardly

straightforward. Non-competes might help existing rms,

but they do so at the expense of workers and would-be

entrepreneurs. us policymakers are tasked with balancing

the interests of these parties, some of whom are more vocal

than others. In Massachusetts, for instance, rms as well

as trade associations have spent nearly six gures lobbying

state legislators against reforming non-compete governance

(Borchers 2014). Workers, by contrast, do not have organized

representation in these debates. Almost by denition, start-

ups not yet founded do not have a voice, except perhaps to the

extent that venture capitalists can advocate for their interests.

Even with all interests represented in the policy discussion,

dierent states could come to dierent conclusions regarding

the ideal enforcement policy. States that choose to enforce

non-competes can do so more or less strictly, as explained in

box 1.

However, whether courts should enforce non-compete

agreements is not the only—and not necessarily the most

important—aspect of non-compete governance. Below, I

propose a series of reforms to both the use and the enforcement

of non-competes.

NOTICE AND NEGOTIATION

Apart from enforcement policy, the process by which employees

sign non-competes deserves careful examination. Because

a non-compete is a contract between an employer and an

employee, employers must obtain signatures from employees.

Ideally, workers would bargain over the terms of a potential

non-compete with various potential employers at the same time

TABLE 1.

Selected Recent State-Level Policy Changes

State Date Details

Illinois August 2016 The Illinois Freedom to Work Act bans the use of non-competes for workers earning less than the $13.50

minimum wage, and states that any such term in an employment agreement is void (Illinois Freedom to

Work Act 2016).

Idaho March 2016 House Bill 487 stipulates that key employees (among the 5 percent most highly paid) “must show that

[they have] no ability to adversely affect the employer’s legitimate business interests” or else a non-

compete of up to 18 months in duration is presumptively enforceable (Idaho House Bill 487 2016, para. 5).

Utah March 2016 The Utah Post-Employment Restrictions Act restricts non-competes to one year and requires an ex-

employer whose non-compete suit is not upheld to pay its ex-employee’s legal expenses (Utah Post-

Employment Restrictions Act 2016).

Hawaii June 2015 Hawaii Act 158 voids any “non-compete clause or a non-solicit clause in any employment contract

relating to an employee of a technology business” (Hawaii Act 158 2015, sec. 2 (d)).

12 Reforming Non-Competes to Support Workers

that salaries and other terms of employment are negotiated.

Workers would have access to the terms (or even text) of the

proposed agreement and obtain the advice of legal counsel.

However, as described previously, the process by which

employees covenant not to compete with their employers

frequently resembles an ambush more than a negotiation.

Most employees are not asked to sign until aer they have

accepted the job oer, and oen not until they have started

the job. Having already turned down other job oers, workers

lack leverage by which they can productively negotiate the

terms of their non-compete. ey are frequently told that the

contract is nonnegotiable or that they must sign quickly (thus

not allowing time for legal review of a document they might

not fully understand without counsel).

I propose that employers—in advance of hiring—be required

to inform workers that they intend to seek a non-compete

agreement as is currently required in Oregon. A reasonable

amount of time must be provided for workers to adequately

review the proposed contract.

COMPENSATION

A related issue with the timing and transparency of non-

competes concerns their use with employees who have long

since been hired. In some states it is permissible for employers to

require existing employees to sign aerthought non-competes.

at is, as a condition of retaining their existing job, employees

must sign a (revised) non-compete without obtaining any

compensation or other consideration for doing so. Although

workers are free to quit their job rather than sign the new non-

compete, doing so can be nancially destabilizing, and it may

be less advantageous to look for a new job once unemployed.

All of these practices are contrary to the notion that employees

should be bound by employment agreements that they enter

into willingly and to mutual benet.

I therefore propose that, in exchange for current employees

signing a new or revised non-compete, rms be required to

compensate those workers in some manner beyond simply

continuing their employment. In addition, current employees

should have the right to refuse to sign an updated contract

without retaliation, including loss of employment.

JUDICIAL MODIFICATION

In the summer of 2010 citizens of Georgia were asked to vote

on a constitutional amendment with the following wording:

“Shall the Constitution of Georgia be amended so as to make

Georgia more economically competitive by authorizing

legislation to uphold reasonable competitive agreements?”

(Georgia House Resolution 187 2010, section 2).

e proposed amendment passed with 68 percent of the

popular vote.

2

Little did voters realize that they were voting

to authorize a practice that gives rms additional control in

their use of non-competes. Georgia’s provision enables judges

to change the terms of a non-compete contract, rather than

invalidate it entirely, when the original terms are found to be

unenforceable under state law.

For instance, if state law restricted non-competes to a duration

of one year, and the contract in a particular case specied a

two-year term, a judge would previously have been required

to strike down the contract. Under Georgia’s new enforcement

regime, a court can simply rewrite the contract to be one

year in duration and then enforce the modied contract. A

BOX 1.

What Are the Different Ways Non-Competes Are Enforced?

Non-competes are enforced according to state laws—usually the common law but sometimes statutes—that vary considerably

across states. Under the most stringent, business-friendly type of enforcement, courts can rewrite unreasonable provisions in a

non-compete agreement so that the contract conforms to standards, then enforce the modied contract. A related enforcement

doctrine allows courts to strike the unreasonable terms of a non-compete agreement and enforce the remainder of the contract.

In either case, businesses have a diminished incentive to be cautious in the draing of their non-competes, because they face little

prospect of having an overly broad agreement invalidated during a legal proceeding.

So-called red-pencil doctrine is less strict from a worker’s perspective. Courts implementing red-pencil doctrine will neither revise

nor eliminate any provisions—rather, courts will nullify the entire non-compete agreement if any provision does not comply with

state law. Under this standard, employers have a stronger incentive to write non-compete contracts so as to comply with state law

and avoid overbroad provisions.

Of course, a few states do not enforce non-competes, generally speaking. California is the most notable example, having eliminated the

enforcement of non-competes according to its Business and Professions Code 16600 in 1872 (Gilson 1999). Figure 4 shows how non-

compete enforcement varies across the states.

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 13

majority of states (41 out of 50) currently allow some degree of

modication by the courts, as shown in gure 4.

Modifying a non-compete might seem to be a boon for

employees, but in fact the opposite is the case, for three reasons.

1. e practice of judicial modication enables non-competes

to be enforced that would otherwise be struck down (albeit

with reduced scope).

2. e ability of judges to x non-competes could encourage

negligence on the part of rms, which would otherwise

be more careful in draing non-competes that would be

struck down if they do not conform to state law.

3. Firms might even intentionally dra non-compete

contracts with broader scope than is permitted by law. Even

if the non-compete is too broad—say, two years instead of

one—the worst that can happen is that a judge could reduce

the scope and then enforce the contract. But in the absence

of a lawsuit, the employee might continue to believe that

the non-compete would be enforced as written (even with

its overbroad terms, the legality of which the employee

might not fully comprehend).

I therefore propose that states abandon the practice of

allowing judges to modify non-compete agreements. Under

this doctrine, courts would throw out non-competes that

contain one or more unenforceable provisions under state law.

THE CHILLING EFFECT

e possibility for employer negligence and abuse aorded

by courts’ ability to modify and enforce non-competes is

another opportunity for deployment of the chilling eect. As

noted above, very few non-compete lawsuits are even led.

is suggests that the eect of non-competes is experienced

less through the courtroom and more through workers’

expectation that they might be sued. is chilling eect has

been documented in interviews with workers who either

remained in their jobs or took career detours due to a non-

compete they had signed (Marx 2011).

If non-competes have a chilling eect even in the absence

of a lawsuit, then non-compete reforms that only limit the

behavior of a judge in a courtroom might have insucient

eect. Workers might avoid breaching their non-compete

even if their employer were unlikely to sue them to enforce the

Source: Beck Reed Riden LLP 2017; author’s calculations.

Note: The type of enforcement in which courts can rewrite terms of contracts is often called the rule of reformation. When courts can delete provisions but

cannot insert new text, the enforcement doctrine is often called blue pencil. These two types of enforcement are combined in the figure category, “Modified

and enforced even if contract does not comply.”

FIGURE 4.

Non-Compete Enforcement, by State

Not enforced

Enforcement Doctrine

Undecided

Modied and enforced even if contract does not comply

Enforced only if contract complies with state law

WA

OR

CA

NV

ID

MT

WY

UT

AZ

NM

CO

ND

MN

IA

WI

OH

KY

TN

NC

VA

IN

MI

PA

VT

NH

ME

NJ

MD

DE

MA

RI

CT

AL

SD

NE

KS

OK

TX

MO

IL

NY

AR

LA

MS

SC

GA

FL

WV

HI

AK

14 Reforming Non-Competes to Support Workers

contract. For example, a worker might avoid pursuing a job

opportunity at another company for fear that they might be

sued, even if such an opportunity was not clearly in violation of

the contract. Even in California, someone asked to sign a non-

compete who does not know that the contract is unenforceable

under state law might be reluctant to change jobs for fear of

retaliation. As long as rms can use non-compete contracts,

the chilling eect will obtain because there appears to be little

downside to rms asking workers to sign non-competes.

In implementing its 2016 non-compete reform for low-

wage workers, Illinois not only rendered such contracts

unenforceable but also banned rms from using such contracts

at all: “No employer shall enter into a covenant not to compete

with any low-wage employee of the employer” (Illinois

Freedom to Work Act 2016, sec. 10 (a)). e ban on using

non-competes for low-wage workers, in combination with

the state’s Consumer Fraud and Deceptive Business Practices

Act, empowered Attorney General Lisa Madigan to bring legal

action against noncompliant rms that allegedly required low-

wage workers without proprietary or condential information

to be bound by non-competes (Channick 2017).

Note that the Illinois provision does not ban all non-competes

but rather those that are unenforceable on their face. Given

this provision, workers can report violations (and can do so

anonymously) for the state attorney general to investigate.

Public investigations, declaratory judgments, injunctions, and

civil penalties would surely reduce the abuse of non-compete

agreements by rms. Currently, companies have little to lose by

aggressively using non-competes, especially in states that allow

modication and enforcement of overbroad non-competes.

I propose that state attorneys general be empowered through

unfair-employment-practice statutes to eliminate non-competes

that are unenforceable on their face. e threat of legal action

could yield a reverse chilling eect to partially counteract the

deleterious eects on workers.

3

NON-DISCLOSURE AGREEMENTS

Non-competes are just one option that employers can

pursue to protect their legitimate interests. Non-disclosure

agreements (NDAs) are another option, but these agreements

can be dicult and costly to enforce: the former employer

must show that the ex-employee divulged trade secrets or other

proprietary information. By comparison, it is much simpler

to verify whether a non-compete has been violated: one need

only establish that the ex-employee is working at a rival rm.

From an employer’s perspective, a non-compete is a less

costly way of protecting condential information. Moreover,

an NDA cannot guard against the use of nonproprietary

training, whereas a non-compete blocks the ex-employee

from deploying that training elsewhere and thus increases the

value of the investment to the employer. As the peer-reviewed

literature shows, rms are advantaged by the ability to use

non-competes (Conti 2014; Younge and Marx 2016).

At the same time, although an NDA does not specically

block the worker’s career exibility—only the sharing of

proprietary information—a non-compete by denition limits

subsequent career opportunities for the worker. Bound to

their current employer, they might fail to capture the same

compensation they would if they could test their value on the

open market. Indeed, workers subject to non-competes are

less likely to leave their employer; when they do leave, they

tend to also leave their industry or their current geographic

region (Garmaise 2011; Marx 2011; Marx, Singh, and Fleming

2015; Marx, Strumsky, and Fleming 2009).

Policymakers might therefore want to explore legal

instruments for the protection of trade secrets that are at once

more reliable than NDAs and less impactful on workers than

non-competes. ese instruments would be substitutes for

non-competes and could diminish their harmful eects.

One possible approach is that adopted in the settlement of IBM’s

lawsuit to block ex-employee Mark Papermaster from joining

Apple. e term of Papermaster’s non-compete was reduced in

exchange for his agreement to certify in writing at three-month

intervals that he had abided by his NDA. In this way, IBM’s

trade secrets were more tightly protected without blocking

Papermaster from taking a new job (Elmer-Dewitt 2009).

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 15

Questions and Concerns

1. Is trade secret litigation too slow and too costly to rely on as

a replacement for non-competes?

Surely it is easier to prove violation of a non-compete (“Is the

ex-employee now working at a rival?”) than to prove violation

of an NDA (“Did the ex-employee divulge trade secrets?”). But

the non-compete is a blunt instrument with which to compel

adherence to the spirit of an NDA. Non-competes have many

negative implications for individual workers, including those

workers who are abiding by their obligations regarding

condential information.

2. In general, mutually agreed-on contracts are considered

benecial. Why are non-competes dierent?

One might claim that government should refrain from

interfering with contractual relations between consenting

employers and employees and avoid articially restricting the

set of possible employment relationships. Brad MacDougall,

vice president of government aairs at the Associated

Industries of Massachusetts, gave voice to this perspective

when he claimed, “e non-compete issue is really about

choice for both individuals and employers, who should be free

to negotiate contracts of mutual benet” (Regan 2014).

However, the experience and analysis of non-competes

suggests that non-competes are oen not mutually agreed on.

e research highlighted in this chapter shows that the process

of getting workers to sign non-competes oen resembles less a

negotiation than it does an ambush. In addition, workers oen

cannot refuse to sign the non-compete lest they lose their job.

3. Are non-competes really an important issue outside of a

few high-level executive jobs?

It is true that non-compete usage is highest among executives,

but they are also widely used among nonexecutives. Nearly

half of engineers have signed a non-compete, and about a h

of workers in the overall population are currently subject to a

non-compete. Moreover, non-competes are relatively common

among both low-skilled and high-skilled workers.

16 Reforming Non-Competes to Support Workers

Conclusion

E

mployee non-compete agreements remain a controversial

topic, as evidenced by wildly varying policy across

states. is policy variation could be due to dierences

in how state policymakers think about the interests of workers,

existing rms, and would-be entrepreneurs. Research provides

insight into these interests, suggesting that non-competes

discourage mobility and depress wages among workers while

promoting stock market performance among publicly traded

rms. Non-competes make it harder to start new companies

and also act as a brake on their performance by making it more

dicult to attract experienced talent.

Balancing these interests is a delicate matter and probably

rightfully le to states to decide. However, the process by

which employers obtain signatures from employees should

be standardized to ensure that workers are not ambushed

but instead have the ability to negotiate such contracts and

receive legal advice. Moreover, modifying and enforcing non-

competes that were originally unenforceable only serves the

interests of rms at the expense of workers. Given that non-

competes rarely achieve their impact via lawsuits but much

more oen via a chilling eect, states should regulate not

only enforceability in a courtroom but also whether rms are

allowed to compel employee signatures. Finally, state attorneys

general should be empowered to sanction rms that engage in

abusive non-compete practices.

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 17

Author

Matt Marx

Associate Professor, Strategy and Innovation, Boston University

Questrom School of Business

Matt Marx is Associate Professor of Strategy and Innovation

at the Boston University Questrom School of Business and

was previously Associate Professor at the MIT Sloan School

of Management. He studies the mobility of knowledge

workers as well as the commercialization and diusion of new

technologies.

He has published extensively on the impact of employee non-

compete agreements and has testied frequently on behalf of

reform eorts. His work has been recognized with a Kauman

Junior Faculty Fellowship and the INFORMS award for

best innovation and entrepreneurship article published in

Management Science or Organization Science during 2009.

Professor Marx previously worked as a soware engineer and

an executive at technology start-ups SpeechWorks and Tellme

Networks, where he received six patents. He holds a BS in

Symbolic Systems from Stanford University, a master’s degree

from the MIT Media Lab, and an MBA as well as a doctoral

degree from Harvard Business School.

Acknowledgments

I’d like to thank Lee Fleming and Evan Starr for their feedback on earlier dras of this document, as well as John Bauer for

discussions about Illinois’ Freedom to Work Act in conjunction with non-competes.

18 Reforming Non-Competes to Support Workers

Endnotes

1. is nding is not simply an artifact of the automotive industry or general

westward migration; in fact, it is robust to a variety of tests including

pretending that the policy change happened in Ohio or other nearby, mid-

sized Midwestern states that would have been similarly aected by general

migration patterns.

2. As described by Pardue (2011), the text summarizing a constitutional

amendment in Georgia does not have to resemble the actual bill.

3. I am especially grateful to John Bauer of Lawson & Weitzen for discussions

on this point.

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 19

References

Beck Reed Riden LLP. 2017. “Employee Noncompetes: A State by State

Survey.” Fair Competition Law, Boston, MA.

Belenzon, Sharon, and Mark Schankerman. 2013. “Spreading the

Word: Geography, Policy, and Knowledge Spillovers.” Review

of Economics and Statistics 95 (3): 884–903.

Ben-Atar, Doron S. 2004. Trade Secrets: Intellectual Piracy and the

Origins of American Industrial Power. New Haven, CT: Yale

University Press.

Borchers, Callum. 2014, May 18. “Tactics Put the Spotlight on

Noncompete Clauses.” Boston Globe.

Buenstorf, Guido, Christoph Engel, Sven Fischer, and Werner Gueth.

2016. “Non-Compete Clauses, Employee Eort and Spin-O

Entrepreneurship: A Laboratory Experiment.” Research Policy

45 (10): 2113–24.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). 2009. “Employment and Earnings.”

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor,

Washington, DC.

Channick, Robert. 2017, October 26. “Illinois Sues Payday Lender Over

Low-Wage Workers Forced to Sign Noncompete Agreements.”

Chicago Tribune.

Conti, Raaele. 2014. “Do Non-Competition Agreements Lead Firms

to Pursue Risky R&D Projects?” Strategic Management

Journal 35 (8): 1230–48.

Elmer-Dewitt, Philip. 2009, January 28. “IBM Settles; Papermaster to

Join Apple in April.” Fortune.

Ewens, Michael, and Matt Marx. 2017, November. “Founder

Replacement and Startup Performance.” Review of Financial

Studies.

Fallick, Bruce, Charles A. Fleischman, and James B. Rebitzer. 2006.

“Job-Hopping in Silicon Valley: Some Evidence Concerning

the Microfoundations of a High-Technology Cluster.” Review

of Economics and Statistics 88 (3): 472–81.

Garmaise, Mark J. 2011. “Ties that Truly Bind: Noncompetition

Agreements, Executive Compensation, and Firm Investment.”

Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 27 (2): 376–425.

Georgia House Resolution 187, 2009–2010 Gen. Sess., amend. Const.

article III, section VI, paragraph V (2010).

Gilson, Ronald J. 1999. “e Legal Infrastructure of High Technology

Industrial Districts: Silicon Valley, Route 128, and Covenants

Not to Compete.” New York University Law Review 74 (3):

575–629.

Hawaii Act 158, S.B.1227 H.D.2 CD1 (2015).

Idaho House Bill 487 63rd Leg. 2nd Sess., amend. Idaho Code 44-2704

(2016).

Illinois Freedom to Work Act 820 ILCS 90/ (2016).

Marx, Matt. 2011. “e Firm Strikes Back: Non-Compete Agreements

and the Mobility of Technical Professionals.” American

Sociological Review 76 (5): 695–712.

Marx, Matt, and Lee Fleming. 2012. “Non-Compete Agreements:

Barriers to Entry…and Exit?” In Innovation Policy and the

Economy, vol. 12, ed. Josh Lerner and Scott Stern (39–64).

Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Marx, Marx, Jasjit Singh, and Lee Fleming. 2015. “Regional

Disadvantage? Employee Non-Compete Agreements and

Brain Drain.” Research Policy 44 (2): 394–404.

Marx, Matt, Deborah Strumsky, and Lee Fleming. 2009. “Mobility,

Skills, and the Michigan Non-Compete Experiment.”

Management Science 55 (6): 875–89.

Pardue, David. 2011, March. “Failing to Trust the Public: e

Process of Submission of the Enabling Amendment to the

Georgia Constitution for the Restrictive Covenant Act

Was Unconstitutional.” http://tradesecretstoday.blogspot.

com/2011/03/failing-to-trust-public-process-of.html.

Prescott, J. J., Norman D. Bishara, and Evan Starr. 2016.

“Understanding Noncompetition Agreements: e 2014

Noncompete Survey Project.” Michigan State Law Review 2016

(2): 369–464.

Regan, John. 2014, May. “Non-Compete Agreements Protect

Innovation.” Associated Industries of Massachusetts (blog).

Samila, Sampsa, and Olav Sorenson. 2011. “Noncompete Covenants:

Incentives to Innovate or Impediments to Growth.”

Management Science 57 (3): 425–38.

Schwab, Stewart J., and Randall S. omas. 2006. “An Empirical

Analysis of CEO Employment Contracts: What Do Top

Executives Bargain For?” Washington & Lee Law Review 63

(1): 231–70.

Shepherd, Jay. 2010, December. Noncompete Cases Not Slowed by

Economy, Legislation. Gruntled Employees (blog).

Simonds, Christopher. 1990. Samuel Slater’s Mill and the Industrial

Revolution. Parsippany, NJ: Silver Burdett Press.

Starr, Evan, Natarajan Balasubramanian, and Mariko Sakakibara.

2017, January. “Screening Spinouts? How Noncompete

Enforceability Aects the Creation, Growth, and Survival of

New Firms.” Management Science.

Stuart, Toby E., and Olav Sorenson. 2003. “Liquidity Events and

the Geographic Distribution of Entrepreneurial Activity.”

Administrative Science Quarterly 48 (2): 175–201.

Utah Post-Employment Restrictions Act, Chap. 153, 2016 Gen. Sess.

(2016).

Younge, Kenneth A., and Matt Marx. 2016. “e Value of Employee

Retention: Evidence from a Natural Experiment.” Journal of

Economics & Management Strategy 25 (3): 652–77.

Younge, Kenneth A., Tony W. Tong, and Lee Fleming. 2015. “How

Anticipated Employee Mobility Aects Acquisition

Likelihood: Evidence from a Natural Experiment.” Strategic

Management Journal 36 (5): 686–708.

20 Reforming Non-Competes to Support Workers

ADVISORY COUNCIL

GEORGE A. AKERLOF

University Professor

Georgetown University

ROGER C. ALTMAN

Founder & Senior Chairman

Evercore

KAREN ANDERSON

Senior Director of Policy and Communications

Becker Friedman Institute for

Research in Economics

The University of Chicago

ALAN S. BLINDER

Gordon S. Rentschler Memorial Professor of

Economics & Public Affairs

Princeton University

Nonresident Senior Fellow

The Brookings Institution

ROBERT CUMBY

Professor of Economics

Georgetown University

STEVEN A. DENNING

Chairman

General Atlantic

JOHN M. DEUTCH

Institute Professor

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

CHRISTOPHER EDLEY, JR.

Co-President and Co-Founder

The Opportunity Institute

BLAIR W. EFFRON

Partner

Centerview Partners LLC

DOUGLAS W. ELMENDORF

Dean & Don K. Price Professor

of Public Policy

Harvard Kennedy School

JUDY FEDER

Professor & Former Dean

McCourt School of Public Policy

Georgetown University

ROLAND FRYER

Henry Lee Professor of Economics

Harvard University

JASON FURMAN

Professor of the Practice of

Economic Policy

Harvard Kennedy School

Senior Counselor

The Hamilton Project

MARK T. GALLOGLY

Cofounder & Managing Principal

Centerbridge Partners

TED GAYER

Vice President & Director

Economic Studies

The Brookings Institution

TIMOTHY F. GEITHNER

President

Warburg Pincus

RICHARD GEPHARDT

President & Chief Executive Officer

Gephardt Group Government Affairs

ROBERT GREENSTEIN

Founder & President

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

MICHAEL GREENSTONE

Milton Friedman Professor of Economics

Director of the Becker Friedman Institute for

Research in Economics

Director of the Energy Policy Institute

University of Chicago

GLENN H. HUTCHINS

Co-founder

North Island

Co-founder

Silver Lake

JAMES A. JOHNSON

Chairman

Johnson Capital Partners

LAWRENCE F. KATZ

Elisabeth Allison Professor of Economics

Harvard University

MELISSA S. KEARNEY

Professor of Economics

University of Maryland

Nonresident Senior Fellow

The Brookings Institution

LILI LYNTON

Founding Partner

Boulud Restaurant Group

HOWARD S. MARKS

Co-Chairman

Oaktree Capital Management, L.P.

MARK MCKINNON

Former Advisor to George W. Bush

Co-Founder, No Labels

ERIC MINDICH

Chief Executive Officer & Founder

Eton Park Capital Management

ALEX NAVAB

Former Head of Americas Private Equity

KKR

Founder

Navab Holdings

SUZANNE NORA JOHNSON

Former Vice Chairman

Goldman Sachs Group, Inc.

PETER ORSZAG

Vice Chairman of Investment Banking

Managing Director and

Global Co-head of Health

Lazard

Nonresident Senior Fellow

The Brookings Institution

RICHARD PERRY

Managing Partner &

Chief Executive Officer

Perry Capital

PENNY PRITZKER

Chairman

PSP Partners

MEEGHAN PRUNTY

Managing Director

Blue Meridian Partners

Edna McConnell Clark Foundation

ROBERT D. REISCHAUER

Distinguished Institute Fellow& President Emeritus

Urban Institute

ALICE M. RIVLIN

Senior Fellow, Economic Studies

Center for Health Policy

The Brookings Institution

DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN

Co-Founder &

Co-Chief Executive Officer

The Carlyle Group

ROBERT E. RUBIN

Former U.S. Treasury Secretary

Co-Chair Emeritus

Council on Foreign Relations

LESLIE B. SAMUELS

Senior Counsel

Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP

SHERYL SANDBERG

Chief Operating Officer

Facebook

DIANE WHITMORE SCHANZENBACH

Margaret Walker Alexander Professor

Director

The Institute for Policy Research

Northwestern University

Nonresident Senior Fellow

The Brookings Institution

RALPH L. SCHLOSSTEIN

President & Chief Executive Officer

Evercore

ERIC SCHMIDT

Technical Advisor

Alphabet Inc.

ERIC SCHWARTZ

Chairman and CEO

76 West Holdings

THOMAS F. STEYER

Business Leader and Philanthropist

LAWRENCE H. SUMMERS

Charles W. Eliot University Professor

Harvard University

LAURA D’ANDREA TYSON

Professor of Business Administration and

Economics Director

Institute for Business & Social Impact

Berkeley-Haas School of Business

JAY SHAMBAUGH

Director

The Hamilton Project • Brookings 21

Highlights

Firms use non-competes widely in order to minimize recruiting costs, safeguard investments,

and protect intellectual property more easily than is achieved via non-disclosure agreements. But

these benefits come at a cost to workers, whose career flexibility is compromised—often without

their informed consent. In this paper, Matt Marx describes evidence from empirical research on

non-compete agreements and recommends policies to balance the interests of firms and workers.

The Proposal

Mandate that employers inform workers that they intend to seek a non-compete agreement

in advance of hiring. Marx proposes that a reasonable amount of time be provided for workers to

adequately review the proposed contract.

Require employers to compensate existing employees for signing a new or revised

non-compete. Marx recommends that firms be required to compensate these workers in some

manner beyond simply continuing their employment. Employees should retain the right to refuse to

sign an updated contract without retaliation.

Prohibit judges from modifying non-compete agreements. Under this doctrine, courts would

throw out non-competes that contain one or more unenforceable provisions under state law.

Empower state attorneys general through unfair-employment-practice statutes to eliminate

non-competes that are unenforceable.

Institute mechanisms to make non-disclosure agreements easier to enforce. Marx suggests

that non-disclosure agreements could substitute for non-competes and diminish the latter’s

harmful effects.

Benefits

The benefits of non-competes accrue primarily to employers and at the expense of employees.

Moreover, the process by which these parties agree to such contracts only rarely includes a

true negotiation. Rather, employees are routinely strong-armed into signing the contract without

carefully considering its implications. The policies in this proposal would better balance the

interests of firms and workers, limiting non-competes to instances in which they are more likely to

be mutually beneficial.

WWW.HAMILTONPROJECT.ORG

1775 Massachusetts Ave., NW

Washington, DC 20036

(202) 797-6484

Printed on recycled paper.