A Hardwood

Log Grading

Handbook

PB1772

$2.50

Contents

How Much Is a Log Worth? ..........................................1

Veneer, Sawlogs and Other Log Classes .................2

Log Scaling ................................................................3

Table 1. The Doyle Log Rule .......................................4

Log Grading — Relation to Lumber Grading ...........6

Table 2. Summary of the NHLA hardwood

lumber grading rules ............................................7

Log Grading Methods .................................................8

Defects .......................................................................8

USDA Forest Service Hardwood Sawlog

Grading System ...................................................11

Table 3. Summary of Forest Service

Hardwood Log Grading Rule ..............................12

Table 4. Total cutting lengths required

in each grade .....................................................15

Table 5. Sweep deduction (percent) .....................16

Grading a Log Using the Forest Service System ....17

Table 6. Scaling deduction factors .........................18

Clear Face Grading ................................................19

The Log Grading Rules Compared ..........................20

The US Forest Service Log Grading Rule .................20

Clear Face Rules .....................................................20

Weight Scaling .........................................................20

Tree Grading ...............................................................21

Table 7. Summary of US Forest Service Rule

for Tree Grading ...................................................21

Log Bucking Optimization ........................................22

Summary .....................................................................24

References ..................................................................25

1

A Hardwood Log Grading Handbook

Adam Taylor

University of Tennessee

A good understanding of log valuation will

help landowners, loggers, log buyers and saw

millers agree on the fair value for a load of logs.

This handbook briefly summarizes common log

grading rules for hardwoods. Basic concepts in

log scaling, lumber grading and log bucking

optimization are also discussed because each

of these topics relates to log grading.

How much is a log worth?

There are three main factors that buyers

and sellers use to determine the value of a

log: Grade, Scale and Species. Grade is a

measure of the quality of the log and the

lumber that will come from the log. Scale is

a measure of the quantity of lumber within a

log. Different species can be used for different

products and have inherently different value,

regardless of the quality of the lumber. Even

seemingly minor differences in grade or spe-

cies can mean a very different value for logs

– see below for an example:

Prices paid for logs of different species and

grade. An example from East Tennessee in 2009.

All values are in dollars per thousand board

feet, scaled using the Doyle rule.

Walnut Red Oak Poplar

High grade $930 $635 $380

Medium grade $505 $380 $260

Low grade $260 $230 $165

2

Log grading is important because it

helps buyers and sellers settle on a fair price

for a load of logs. Log grades can be used to

predict the proportion of high-quality lumber

that will be produced from that log. This log

grading can also be used to help measure

sawmill efficiency.

Veneer, Sawlogs and Other Log Classes

Some hardwood logs are reserved for the

production of veneer – thin sheets of wood

that are peeled or sliced directly from logs.

These logs are usually very high quality, with

few if any visible defects. Veneer logs may also

be judged on color, growth rate and amount

of sapwood versus heartwood. Veneer logs are

higher value than sawlogs. More information

on veneer, and the grading of veneer logs,

can be found in the publication Factors Affect-

ing the Quality of Hardwood Timber and Logs

for Face Veneer.

1

Sawlogs are those that are sawn into

hardwood lumber and the grading of saw-

logs is the subject of this handbook. These

logs are also called “factory” logs. Logs that

are not of sufficient quality to be a sawlog

may be used for cutting pallet stock or rail-

road crossties, where appearance is not im-

portant, or for pulpwood.

This handbook deals only with hardwoods.

Softwoods such as pine and spruce are gen-

1

Cassens, D.L. 2004. Factors Affecting the Quality of

Hardwood Timber and Logs for Face Veneer. Purdue

University publication FNR239. Available for down-

load from http://www.ces.purdue.edu/extmedia/

FNR/FNR-239.pdf

3

erally used for making structural products, for

example the studs used for framing a house.

Softwoods are graded using different rules that

focus on strength-reducing defects.

Log Scaling

Scaling is used to predict the amount of

lumber that will be sawn from a log. The amount

of lumber is measured in board feet, where one

board foot is 1” x 12” x 12”, or any dimension

with the same volume of wood. For example, a

board 2” x 6” x 8’ contains 8 board feet.

There are different log rules that are used

for scaling in different regions and for different

products. The three most common log scales

are the Doyle rule, the Scribner rule and the

International ¼” Rule. By tradition, the Doyle

Scale is the most commonly used scaling rule

used in Tennessee (Table 1.)

2

The Doyle Rule often underestimates the

yield of lumber for small logs and for modern,

more efficient sawmills (e.g. band mills). This

underestimating can lead to “overrun”, when

the actual yield is more than the scaling pre-

dicted. Figure 1 shows a comparison of the

Doyle scale to the International ¼” Rule, which

more accurately predicts the true yield.

Log prices are normally different depend-

ing on the rule used, reflecting the differences

in the scale resulting from each rule. Thus, the

2

For more information on scaling, and conversions

among the log rules, see Understanding Log Scales

and Log Rules by Brian Bond. University of Tennessee

Extension PB1650. Download available at www.

utextension.utk.edu/publications/pbfiles/Pb1650.pdf

4

Table 1. The Doyle Log Rule.

Log Length (feet)

8 10 12 14 16

Scaling

Diameter

(inches)

------------Yield of Lumber ------------

(board feet)

8 8 10 12 14 16

9 13 16 19 22 25

10 18 23 27 32 36

11 25 31 37 43 49

12 32 40 48 56 64

13 41 51 61 71 81

14 50 63 75 88 100

15 61 76 91 106 121

16 72 90 108 126 144

17 85 106 127 148 169

18 98 123 147 172 196

19 113 141 169 197 225

20 128 160 192 224 256

21 145 181 217 253 289

22 162 203 243 284 324

23 181 226 271 316 361

24 200 250 300 350 400

25 221 276 331 386 441

5

average log value will be the same regardless

of the scaling rule that is used.

Special rules for certain species or prod-

ucts are used in some locations. For example,

some buyers use a “cedar rule” for predicting

the lumber yield from eastern redcedar logs,

which are small and irregularly shaped.

Species is another important factor in

determining log value. For example, top grade

walnut, cherry or hard maple logs can be

worth two- or three-times as much as hickory,

soft maple or poplar logs of the same size and

quality. This is because the products made

from those species are worth more and there

are fewer top quality logs of the high-value

species available. Species differences may

Figure 1. The predicted lumber yield using the Doyle scale compared

to the International ¼” rule. The International Rule is fairly accurate for

all log diameters, while the Doyle Rule underestimates the true yield

of lumber for smaller logs. The actual yield of lumber from a scaled

log will vary with mill technology, wood species and other factors.

Log Diameter (inches)

10 15 20 25 30

Predicted Lumber Yield

(percent)

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

D

o

y

le S

c

a

le

International 1/4" Rule

Overrun

6

be stated explicitly in some log grading rules.

Other log grading rules grade all species of

logs in the same way, with buyers paying dif-

ferent prices for logs of the same grade but of

different species.

There are regional differences in pricing

of logs and lumber products, because the

wood quality of certain species is thought to

be superior in some areas. For example, cherry

logs from the northeastern United States are

believed to contain higher-quality lumber and

thus higher prices are paid for cherry logs from

that area. There are also local variations in log

prices. For example, if there are many sawmills

within a reasonable hauling range of a timber

harvest, this can increase the demand – and

thus the price paid – for logs. Finally, prices

paid for logs can vary substantially with fluc-

tuations in demand due to seasonal changes

and overall economic trends.

3

Log Grading —

Relation to Lumber Grading

Most hardwood logs are sawn into lumber.

The value of this lumber, and thus of the log, is

determined in part by the lumber grade. The

grade of hardwood lumber is determined by

a visual inspection of each board according

to rules developed by the National Hardwood

3

Information on prices trends in log and lumber

markets are available from a number of sources

including the including Tennessee Division of

Forestry (www.state.tn.us/agriculture/forestry/

tfbp.html), the Hardwood Market Report (www.

hmr.com/), the Hardwood Review (www.

hardwoodreview.com/) and TimberMart South

(www.tmart-south.com/tmart/)

7

Lumber Association (NHLA - Table 2). The most

important factors in determining lumber grade

are width, length and yield of defect-free

wood (“clear cuttings”).

As shown in Table 2, high-grade lumber

must be relatively long, wide and clear of de-

fects. Therefore high grade logs must be long,

large in diameter and contain mostly clear

wood. Larger logs are also preferred in log

grading because they cost less to process per

unit of lumber produced.

Table 2. Summary of the NHLA hardwood lumber

grading rules. Adapted from NHLA, 2003.

Grade

Lumber Requirements

Min.

Board

Length

(feet)

Min.

Board

Width

(inches)

Clear cuttings

(poor face)

Total

yield

Min.

size

Max.

number

FAS (the

top grade)

8 6 83.3% 4” x 5’

3” x 7’

4

*

Selects 6 4 83.3%

(good

face)

1 Common 4 3 66.6% 4” x 2’

3” x 3’

5

*

2 Common 4 3 50% 3” x 2’ 7

*

3 Common

(the lowest

grade)

4 3 33.3% 3” x 2’ --

*

The maximum number of cuttings allowed depends

on board size. The actual number is usually fewer.

8

Although low-quality logs will produce

some high-grade lumber, higher-grade logs pro-

duce a higher proportion of better quality lum-

ber. That is why high-grade logs have a higher

value. An example is given in the table below.

Log Grading Methods

Unlike lumber grading, there is no one

system that is widely accepted for grading

logs. The United States Forest Service has de-

veloped a log grading system based on the

yield of “clear cuttings” from faces of the log.

Alternatively, many buyers use a “clear face”

system, where the number of clear (defect-

free) faces on the logs is the basis for deter-

mining quality. Some sawmills also buy logs on

the basis of weight. Buying by weight assumes

an average grade for the whole load.

Defects

Defects are features that reduce the qual-

ity or quantity of the lumber that will be sawn

from the log. For the US Forest Service log grad-

ing rule, defects are defined as follows:

Grade and value of lumber produced from

black cherry logs of different grades. Expressed

as board feet of 4/4 (1” thick) lumber sawn from

16” diameter, 12’ long logs, based on prices

for Appalachian hardwoods in 2009.

Log Grade

FAS &

Select #1 C #2 C #3 C

Total

Lumber

Value

High (F1) 59 20 17 12 $111

Medium

(F2)

28 38 22 20 $79

Low (F3) 15 46 23 23 $65

9

● Grade defects include anything that re-

duces lumber value. These include stem

bulges, splits, rot and insect or bird holes.

Abnormalities on the surface of a log must

extend into the log more than 15% of the

diameter to be considered a defect (see

“Quality Zones” in Figure 2). Knots, and bark

distortions where the tree has grown over

old knots, are the most common defects.

These are also the most important defects

because knots extend to the center of the

log and will appear on all the lumber sawn

from that part of the log.

Small bark distortions, that do not clearly

indicate an overgrown knot, are not consid-

ered to be a defect in 15”+ diameter logs.

Horizontal breaks in the bark are not defects.

Abrupt bumps are defects, but clear cuttings

can extend ¼ of the length of the bump.

Bumps with gradually sloping sides (length

12+ times the height) can be ignored.

● End defects are determined by looking at

both ends of the log. Any abnormality in

the “heart center” (the innermost 1/5 of

the diameter) can be ignored for grading

purposes. End defects are classified in the

following three categories:

■ Unsound end defects include knots, de-

cay (rot) and shake. If the defect extends

more than half the distance from the

heart zone to the bark (both Quality zones

– Figure 2), then a clear cutting cannot be

taken over it. The distance up the log that

10

the defect extends should be estimated;

a clear cutting can extend over 1/3 of the

estimated length of the defect.

■ Sound end defects include stain and

slight dote (the beginning of rot) and are

restricted in Grades 1 & 2.

• Grade1–notmorethan½ofeitherend

• Grade2–notmorethan3/5ofeither

end(limitedto½of16”diameterand

smaller logs.

■ Specific end defects include bird peck,

wormholes, spots and streaks. If these de-

fects cover more than half the distance

from the heart center to the bark under

three or more faces at one end, or two

faces at both ends, lower Grade 1 & 2

one grade.

● Scaling defects reduce the amount, or vol-

ume, or useable lumber. Rot and large holes

Figure 2. Quality

zones in a hardwood

log. Abnormalities

must occur in both the

inner and outer quality

zones to be consid-

ered a defect for grad-

ing purposes. Defects

in the heart center are

ignored for grading

purposes. Adapted

from McKenna, 1981.

HEART

CENTER

R = 20% D

INNER QUALITY

ZONE

R = 15% D

OUTER QUALITY

ZONE

R = 15% D

QUALITY ZONE

(Inner plus outer)

R = 30% D

11

produce no lumber and thus can reduce

not only the grade (quality) of the lumber

produced from a log but also the quantity

(scale). Scaling deductions can be made

to account for these defects when scaling

the log but these defects are also consid-

ered in log grading.

USDA Forest Service Hardwood Sawlog

Grading System – a clear cutting method

The Forest Service has developed a system

to organize sawlogs into one of three grades.

Grade 1 (or “F1”, where F stands for ‘factory’) is

the highest (top quality), grade 2 (F2) the next

best, and grade 3 (F3) is the lowest grade.

The Forest Service grading system predicts the

yield of 1 Common and better grades of lumber

produced from the log. This is estimated based

on the whether the log is a butt or upper cut,

the log length and diameter, and the number

and location of defects on the log.

Table 3 summarizes the requirements for

each of the three grades. The factors used in

grading are listed in the left-hand column.

● Position in tree. “Butt” logs come from the

base of the tree and are preferred because

there is usually more clear wood in that part

of the tree stem. Butt logs can be identified

by the flare at the base of the log and the

presence of the notch that was used to di-

rect the falling tree. Upper logs are also ac-

ceptable for all three grades, except smaller

grade 1 logs (13” – 15” diameter), which must

be butt cuts only.

12

Table 3. Summary of Forest Service Hardwood Log Grading Rule.

Adapted from McKenna, 1981.

Grading Factor Grade 1 (F1) Grade 2 (F2) Grade 3

(F3)

Position in tree Butt

only

Butt or upper Butt or upper Butt or

upper

Diameter 13”-

15”

16”-

19”

20”+ 11” 12”+ 8”+

Length 10’+ 10’+ 8’-

9’

10’-

11’

12’+ 8’+

Clear cuttings

on 3

rd

best/2

nd

worst face

Length 7’ 5’ 3’ 3’ 2’

Number 2 2 2 2 3 No limit

Yield 5/6 2/3 3/4 2/3 2/3 ½

Sweep

If < ¼ of end in

sound defects

15% 30% 50%

If > ¼ of end in

sound defects

10% 20% 35%

Total scaling deduction 40% 50% 50%

13

● Diameter. The diameter of a log for grad-

ing (and scaling) is the diameter inside

the bark at the small end. Most logs are

not truly round, so two (or more) diameter

measurements should be made and the

average value used. The grading rule speci-

fies minimum diameters because larger

diameter logs tend to contain a higher pro-

portion of defect-free wood and because

high-grade lumber must be wide.

● Length. The length of a log for log grading

and scaling is the length in feet, without

trim. Most log buyers require 4” or 8” of trim

allowance.

● Clear cuttings. As in the lumber grading

rules, clear cuttings are the basis of the For-

est Service log grading system. Clear cut-

tings are sections of the log that are free

from defects. Clear cuttings are determined

on the grade face.

■ Choosing the grade face. The grade face

is determined by dividing the surface of

the log into four equal faces. This should be

done such that one face is the “worst” – i.e.

it contains the most defects (Figure 3). The

next best face is the grade face. The other

two faces should be at least as good, or

better, than the grade face

■ Clear cutting length. The minimum

length of a clear cutting is specified. High-

er grade logs require longer cuttings. All

cuttings must be the full width of the face.

14

■ Maximum number of clear cuttings. For

grade 1 (F1) logs, only two cuttings are

allowed on the grade face. Some F2, and

all F3 logs, can have 3 cuttings.

■ Clear cutting yield. The yield of clear cut-

tings on the grade face is calculated as

the total length of the cuttings divided by

the total length of the log (no trim). High-

er grade logs must have a higher yield.

Table 4 provides calculations of total clear

cutting lengths for different log lengths.

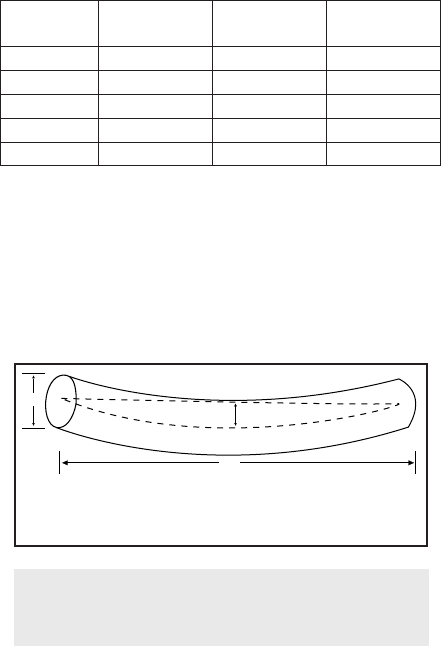

● Maximum Sweep. Curved logs are more

difficult to process and they produce a lower

yield of good-quality lumber. Therefore the

log grading rule specifies the maximum

Divide the log into four faces…

…ignore the worst face and grade

the next worse face.

Figure 3. Determining the grade face of a log.

Adapted from Rast et al, 1973.

Grade Determining Face

15

amount of sweep that is allowed for each

grade. Sweep is measured as the maximum

deviation of the log from a straight line

(Figure 4). The sweep deduction can be

determined using Table 5. The rule permits

less sweep allowance for logs with sound

defects covering more than 1/4 of either end.

Example: A 14’ long log, with a 20” scaling

diameter, has 8” of sweep. The sweep de-

duction is 30% (Table 5).

● Total scale and sweep deduction. The

rules limits the amount of unusable wood in

a log. The defect length factor multiplied

by the defect cross-section factor equals

Figure 4. Measuring sweep on a curved log. This log has 8” of

sweep. From McKenna, 1981

8”

16’

20”

Table 4. Total cutting lengths required in each grade.

Adapted from McKenna, 1981.

Log length

(feet)

Grade 1 (F1)

(5/6 yield)

Grade 2 (F2)

(2/3 yield)

Grade 3 (F3)

(1/2 yield)

8 -- 6’ (3/4 yield) 4’

10 8’4” 6’8” 5’

12 10’ 8’ 6’

14 11’8” 9’4” 7’

16 13’4” 10’8” 8’

16

Table 5. Sweep deduction (percent). Adapted from McKenna, 1981.

Sweep (inches) Diameter at the small end inside the bark (inches)

8-10 foot logs 14-16 foot logs 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30

- 3 12 10 8 7 6 6 5 5 4 4 4 3

3 4 25 20 17 14 12 11 10 9 8 8 7 7

4 5 38 30 25 21 19 17 15 14 12 12 11 10

5 6 50 40 33 29 25 22 20 18 17 15 14 13

6 7 50 42 36 31 28 25 23 21 19 18 17

7 8 50 43 38 33 30 27 25 23 21 20

8 9 50 44 39 35 32 29 27 25 23

9 10 50 44 40 36 33 31 29 27

10 11 50 45 41 38 35 32 30

11 12 50 45 42 38 36 33

12 13 50 46 42 39 37

13 14 50 46 43 40

14 15 50 46 43

15 16 50 47

16 17 50

11-13 foot logs

3 19 15 12 11 9 8 8 7 6 6 5 5

4 31 25 21 18 16 14 12 11 10 10 9 8

5 44 35 29 25 22 19 18 16 15 13 12 12

6 45 38 32 28 25 22 20 19 17 16 15

7 46 39 34 31 28 25 23 21 30 18

8 46 41 36 32 30 27 25 23 22

9 47 42 38 34 31 29 27 25

10 47 42 39 35 33 30 28

11 48 43 40 37 34 32

12 48 44 40 38 35

13 48 44 41 38

14 48 45 42

15 48 45

16 48

17

Table 5. Sweep deduction (percent). Adapted from McKenna, 1981.

Sweep (inches) Diameter at the small end inside the bark (inches)

8-10 foot logs 14-16 foot logs 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30

- 3 12 10 8 7 6 6 5 5 4 4 4 3

3 4 25 20 17 14 12 11 10 9 8 8 7 7

4 5 38 30 25 21 19 17 15 14 12 12 11 10

5 6 50 40 33 29 25 22 20 18 17 15 14 13

6 7 50 42 36 31 28 25 23 21 19 18 17

7 8 50 43 38 33 30 27 25 23 21 20

8 9 50 44 39 35 32 29 27 25 23

9 10 50 44 40 36 33 31 29 27

10 11 50 45 41 38 35 32 30

11 12 50 45 42 38 36 33

12 13 50 46 42 39 37

13 14 50 46 43 40

14 15 50 46 43

15 16 50 47

16 17 50

11-13 foot logs

3 19 15 12 11 9 8 8 7 6 6 5 5

4 31 25 21 18 16 14 12 11 10 10 9 8

5 44 35 29 25 22 19 18 16 15 13 12 12

6 45 38 32 28 25 22 20 19 17 16 15

7 46 39 34 31 28 25 23 21 30 18

8 46 41 36 32 30 27 25 23 22

9 47 42 38 34 31 29 27 25

10 47 42 39 35 33 30 28

11 48 43 40 37 34 32

12 48 44 40 38 35

13 48 44 41 38

14 48 45 42

15 48 45

16 48

the scale deduction (Table 6). The scale

deduction is then added to the sweep de-

duction to give the total scale and sweep

deduction.

Example: The log in previous example has

a 6” diameter round hole in the butt end

that extends 4’ (30%) up the log. The defect

length factor is 0.5 and the defect cross-

section factor is 8 (Table 6). The total scale

deduction is 0.5 x 8 = 4. The total scale and

sweep deduction is 4 + 30 (from the previ-

ous example) = 34%.

Grading a Log Using the

Forest Service System

The process for grading a log is relatively

simple. The biggest challenge is identifying the

location and extent of defects.

● Step 1. Measure diameter and length. This

is also required for scaling the log. Note if

the log is a butt or upper section.

● Step 2. Find the grade face. Faces should

be arranged to produce the highest grade

log possible. Ignore the worst face and

grade the next worst (or third best) face.

Seams that can be positioned between two

faces can be ignored.

● Step 3. Determine the size, number and

yield of clear cuttings on the grade face.

● Step 4. Check that sweep and scale de-

ductions are within the allowed limits.

The requirements listed Table 3 are the

minimum requirements for logs for each

grade. Each log must meet all of the require-

18

Table 6. Scaling deduction factors. To determine the scale deduction, multiply the length factor by the cross-section factor.

Adapted from McKenna, 1981.

Length factors

Log diameter (inches)

Length of log that has defect (percent)

10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

8 1.2 2.4 3.5 4.7 5.9 7.1 8.2 9.4 10.6 11.8

9 .9 1.8 2.7 3.6 4.5 5.4 6.3 7.2 8.1 9.0

10 .7 1.4 2.1 2.8 3.6 4.3 5.0 5.7 6.4 7.1

11 .6 1.1 1.7 2.3 2.9 3.4 4.0 4.6 5.2 5.8

12 .5 1.0 1.4 1.9 2.4 2.9 3.3 3.8 4.3 4.8

13 .4 .8 1.2 1.6 2.0 2.4 2.8 3.2 3.6 4.0

14 .3 .7 1.0 1.4 1.7 2.0 2.4 2.7 3.1 3.4

15 .3 .6 .9 1.2 1.5 1.8 2.1 2.4 2.6 2.9

16 .3 .5 .8 1.0 1.3 1.5 1.8 2.0 2.3 2.6

17 .3 .4 .7 .9 1.1 1.4 1.6 1.8 2.0 2.3

18 .2 .4 .6 .8 1.0 1.2 1.4 1.5 1.8 2.0

19 .2 .4 .5 .7 .9 1.1 1.2 1.4 1.6 1.8

20 .2 .3 .5 .6 .8 1.0 1.1 1.3 1.4 1.6

21 .2 .3 .4 .6 .7 .9 1.0 1.2 1.3 1.4

22 .1 .3 .4 .5 .7 .8 .9 1.0 1.2 1.3

23 .1 .2 .4 .5 .6 .7 .8 1.0 1.1 1.2

24 .1 .2 .3 .4 .5 .6 .8 .9 1.0 1.1

25 .1 .2 .3 .4 .5 .6 .7 .8 .9 1.0

Cross-section factors

Width (short axis) of defect (inches) Height (long axis) of defect (inches)

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

2 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 5 6 6 7 7 8 8

3 3 3 4 5 5 6 7 8 8 9 10 10 11

4 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 10 11 12 13 14

5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 14 15 16 17

6 8 10 11 12 13 15 16 17 18 19

7 11 12 14 15 17 18 19 21 22

8 14 16 17 19 20 22 23 25

9 17 19 21 23 24 26 28

10 21 23 25 27 29 31

11 25 27 29 31 33

12 29 32 34 36

13 34 36 39

14 39 42

15 44

19

ments for each grade. Logs that do not meet

Grade 3 are “cull” or below grade.

Clear Face Grading

Clear face log grading rules are used by

many log buyers. Many variations on clear face

grading rules exist but, like the Forest Service sys-

tem, these rules require minimum diameters and

lengths for logs. Clear-face log grading rules

also divide the log into four equally-sized faces;

however, instead of examining the clear cuttings

on the grade face, the number of completely

clear (defect free) faces are counted. Higher

grades require more clear faces. Although no

standard clear-face log grading rule exists, figure

5 gives an example of a clear face grading rule.

Grade Diameter Length

Clear

Faces

Super Prime 18” 14’ 4

Prime 1 18” 12’ 4

Prime 2 15” 10’ 4

Select 1 16” 10’ 3

Select 2 15” 10’ 3

#1 14” 8’ 2

#2 12” 8’ 1

#3 10” 8’ 0

Notes:

•Poplarminimum20”diameterforPrime

•Whiteoak,HickoryandBeech-minimumlengthof10’

Figure 5. An example of a clear face grading rule. Note that this

rule is specific to this mill – other log buyers will have different

requirements.

20

The Log Grading Rules Compared

The US Forest Service Log Grading Rule

The Forest Service system for grading logs

has a number of advantages. As a published

standard it can be widely used and under-

stood. It is also independent of tree species, so

any log can be graded using the same meth-

od. However, the biggest advantage is that it

can be used to predict the amount of high-

grade lumber that will be produced from a log.

The Forest Service system was developed over

many years by measuring over 20,000 logs

and grading the lumber that was produced

from those logs. Based on those measure-

ments, the following predictions are possible:

Grade 1 (F1)

…logs will

produce…

60%+

…1Common

or

better

lumber

Grade 2 (F2) 40-60%

Grade 3 (F3) Less

than

40%

Clear Face Rules

Some people prefer clear face grading

rules because they can be simple to apply;

there is no need to calculate clear cutting

yield. Clear face rules usually have more than

three grades, which allows for more price lev-

els for logs of different quality.

Weight Scaling

When buying logs by weight, an average

grade (and scale) of the logs in the load is as-

sumed. Weight scaling has the advantage of

being easy and fast; however, it provides very

21

little information about the quality and quan-

tity of lumber that will be produced.

Tree Grading

The principles of log grading can be ap-

plied to standing trees to estimate the value

of the log contained within the bole. Table 7

shows a summary of a tree grading system

developed by the United States Forest Service.

This tree grading system is very similar in many

ways to the log grading system.

Because the logs have not yet been cut

from the tree, the grading section can be lo-

cated anywhere in the bottom 16’ of the tree.

Once the grading section has been located,

Table 7. Summary of US Forest Service Rule for Tree

Grading. Adapted from Hanks, 1976.

Grade 1 Grade 2 Grade 3

Grading section Best 12’ in 16’ butt section

Diameter at

breast height

(DBH – inches)

16 13 10

Diameter at

top of grading

section (inside

bark – inches)

13 16 20 11 12 8

Clear cuttings (on three best faces)

Min. length (feet) 7 5 3 3 3 2

Max. number on

each face

2 2 3 No limit

Min. yield per

face

5/6 2/3 1/2

Cull deduction

(percent)

9 9 50

22

the diameter of the tree is measured at breast

height and the scaling diameter at the top of

the grading section is estimated. Then, the size

and number of clear cuttings on the grade

face are determined. Of course, because

the tree has not yet been cut, possible end

defects are not a factor; only defect indica-

tors on the surface of the tree are considered.

Tree grading also can be used to predict the

proportion of high-grade lumber that can be

sawn from the tree (see Hanks, 1976).

Log Bucking Optimization

After a tree is felled and limbed, it is

“bucked” into logs. The location of the bucking

cuts on the tree stem can greatly influence

the grade, and thus the value, of the resulting

logs. Studies have shown that improved buck-

ing practices can increase the average value

of logs by 15 to 35%. Loggers should keep the

following rules-of-thumb in mind when making

bucking decisions:

● Know the market. Different log buyers use

different log grading methods and small

differences in the grading system can result

in large differences in log values. By being

familiar with what the buyer wants, a logger

can make bucking decisions that improve

the value of the logs cut from trees.

● Find the best log. In general, it is best to

locate the top grade log from a stem first

and then arrange the other bucking cuts

around it. Often this highest-value log will

be the butt log but in many cases the best-

23

grade log will be located further up the

stem. In some cases, this process will involve

discarding cull sections at the butt end.

Because of the relatively high value of top-

grade logs, it is usually advantageous to

lose some scale (volume) if it will result in a

higher grade (quality) log.

It is also important to remember that

longer lengths of logs do not necessarily

have higher value. Although the minimum

length requirements for various grades and

products must be met, the length of a log

should be adjusted (if possible) to yield the

highest grade logs from the tree.

Example: In the white oak log pictured be-

low, the grade can be improved from #2

(log A) to #1 (log B) by cutting off the butt

2’. Even though the scale is reduced, the

overall value of the log is higher because #1

logs sell for $800/thousand board feet and

#2 sell for $500/thousand.

14”

14’2’

Scale = 88’

Grade = 1 ($800/thousand)

Value = $70

(Cull)

A

16’

14”

Scale = 100’ (Doyle scale)

Grade = 2 ($500/thousand)

Value = $50

24

● Keep logs straight. As described above,

sweep can lower log grade. For this reason,

it is often best to buck stems where they

curve. The resulting logs will be straighter

and could be a higher grade.

● Put the defects on the end. Many log buy-

ers will consider the location of defects in

a log, especially if they are using the Forest

Service’s grading system. Defects that are

close to the ends of a log are easier for the

sawyer to cut around (to produce clear

lumber). For this reason, defects near the

ends of a log often won’t reduce the grade

as much as defects that are in the middle.

More information on hardwood log buck-

ing is available on the internet at http://www.

hardwoodvip.org/

Summary

A knowledge of how hardwood log values

are determined can help buyers and sellers

decide on a fair price for timber sales. Mea-

suring incoming log quality can also help

sawmills to evaluate the efficiency of their mills.

Log values are a function of the grade (qual-

ity), scale (size) and wood species. Log grade

affects the quality mix of lumber that will be

sawn from a log; high quality logs produce a

larger proportion of high quality lumber. Log

grading rules vary by region and individual

buyer but the principles remain the same ev-

erywhere: High grade logs have few defects

(especially knots), are large in diameter, and

are of a minimum length. Small differences in

25

grade can mean large differences in price,

so it is important to understand how grade is

determined. Loggers in particular should be

familiar with the log market and applicable

grading rules so that they can make buck-

ing decisions that maximize the value of logs

coming from a tree.

References

Hanks, Leland F. 1976. Hardwood Tree Grades

for Factory Lumber. USDA Forest Service

Research Paper NE-333.

Hardwood Value Improvement Program

(HVIP). 2006. Increase Log Quality Through

Improved Bucking. Internet website at

http://www.hardwoodvip.org/. Accessed

November 20, 2006.

Kenna, Karen M. 1981. Grading Hardwood

Logs for Standard Lumber: Forest Service

Standard Grades for Hardwood Factory

Lumber Logs. Formerly Publication No.

D1737-A, Forest Products Laboratory, USDA

Forest Service. Revised 1981.

Rast, Everette D., David L. Sonderman and

Glenn L. Gammon. 1973. A guide to

hardwood log grading. USDA Forest Service

General Technical Report NE-1

National Hardwood Lumber Association

(NHLA). 2003. Rules for the Measurement &

Inspection of Hardwood & Cypress. PO Box

34518, Memphis TN 38184. www.nhla.com

Programs in agriculture and natural resources, 4-H youth development,

family and consumer sciences, and resource development.

University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture,

U.S. Department of Agriculture and county governments cooperating.

UT Extension provides equal opportunities in programs and employment.

PB1772-1M-12/09 (Rev) E12-4910-122-002-10

Visit the UT Extension Web site at

http://www.utextension.utk.edu/