1

Teaching portfolio

for

Annelise Ly, Associate professor,

Department of professional and

intercultural communication (FSK)

1 March 2021

2

Table of contents

1. Biography: My teaching history in a nutshell ...................................................................................... 4

2. Teaching philosophy ............................................................................................................................. 5

2.1 Students learn by practicing the discipline ................................................................................................... 5

2.2 Students learn in a safe and supportive environment .................................................................................. 6

2.3 A culture for feedback and reflection. .......................................................................................................... 6

3. Reflections on own educational development ....................................................................................... 7

3.1 FRA10: Fransk økonomisk språk and FRA20: Frankrike i dag: økonomi, samfunn og kultur........................ 7

3.2. FSK10: East Asian culture and communication ........................................................................................... 8

3.3. INB431/ CEMS402: Global leadership practice ............................................................................................ 9

4. Teaching and assessment repertoire ................................................................................................... 10

4.1 FRA10 and FRA20 ....................................................................................................................................... 10

4.2 FSK10 .......................................................................................................................................................... 11

4.3. CEMS402 ................................................................................................................................................... 12

5. Pedagogical materials ......................................................................................................................... 14

6. Supervision ........................................................................................................................................ 15

7. Teaching planning and contributions in FSK and NHH .......................................................................... 15

8. Dissemination .................................................................................................................................... 16

9. Evidence of student learning ............................................................................................................... 17

9.1. Student evaluations ................................................................................................................................... 17

9.2. Emails from programme directors ............................................................................................................. 17

9.3. Student testimonials .................................................................................................................................. 17

9.4. Assessments by external examiners .......................................................................................................... 17

9.5 Students’ work ............................................................................................................................................ 18

10. Conclusion: a few reflections on online teaching .................................................................................... 18

11. Appendices ............................................................................................................................................ 19

A. Teaching CV ............................................................................................................................................ 19

B. FRA10: examples of activities and assignments ..................................................................................... 23

Example of teaching plan ............................................................................................................................ 23

Activities in class ......................................................................................................................................... 24

Example of peer-review, using Mentimeter ................................................................................................ 25

Example of role-play .................................................................................................................................... 26

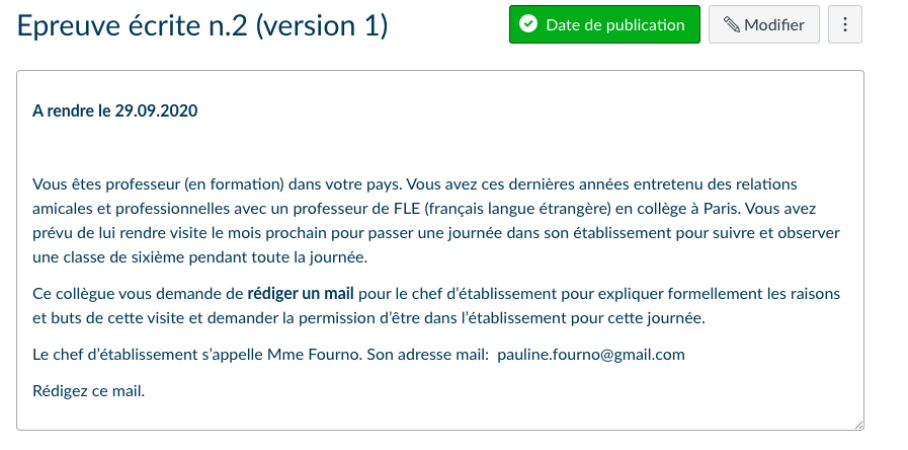

Example of assignment: writing a professional email ................................................................................. 27

C. FRA20: examples of set of activities, assignments and student deliverables ......................................... 28

3

Example of activity package ........................................................................................................................ 28

Example of course approval activity ............................................................................................................ 30

Example of student deliverables ................................................................................................................. 31

D. FSK 10: examples of class activities and assignments ............................................................................ 35

Homework with readings and questions and case study in class ................................................................ 35

Case study and teaching plan ...................................................................................................................... 36

Example of assignment ................................................................................................................................ 37

E. CEMS402: example of activities, assignments and student deliverables ................................................ 38

Individual and team test: multiple choice question (extract)...................................................................... 38

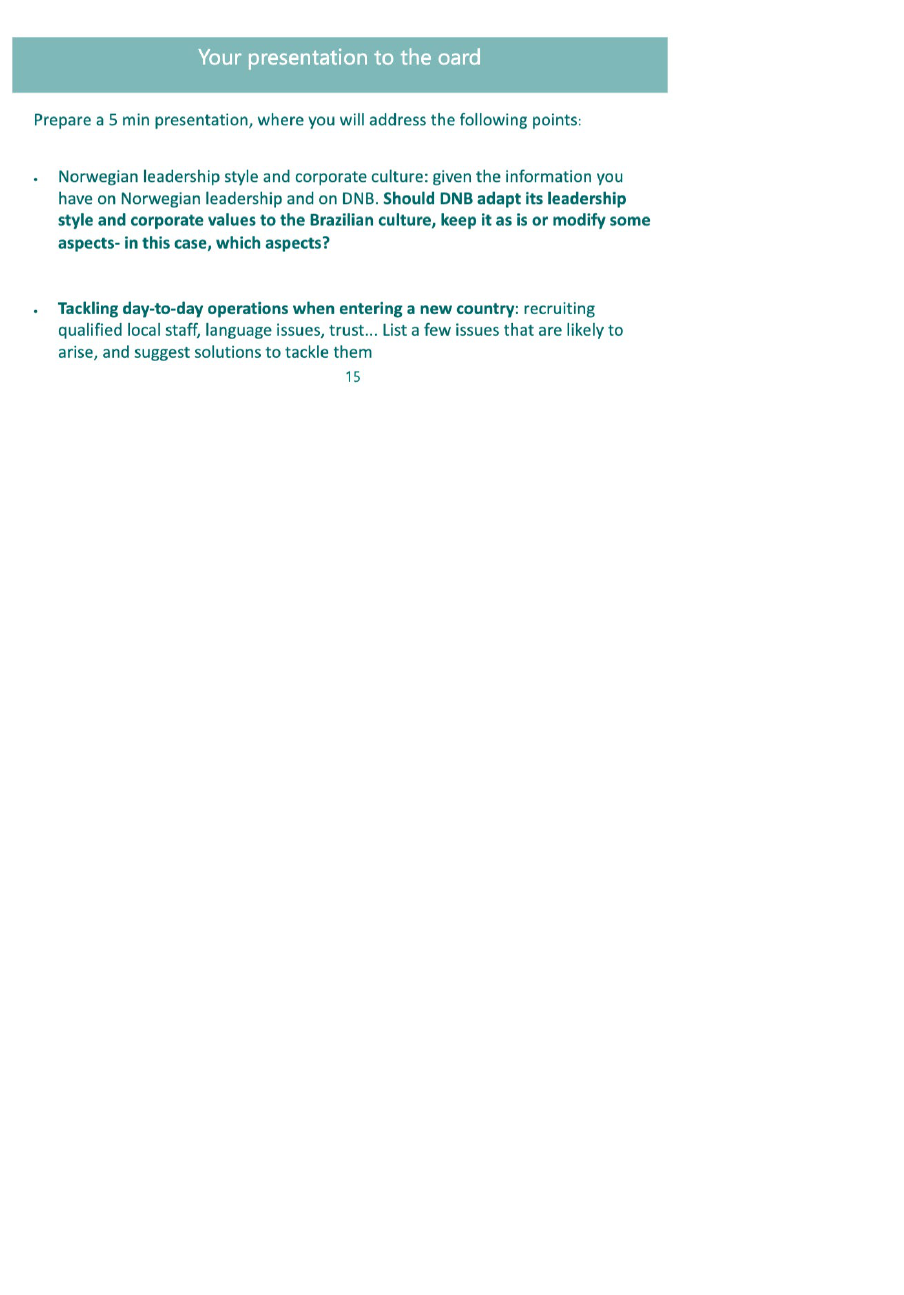

Example of application activity: Live case study. ......................................................................................... 39

Example of experiential learning 1) leadership in TBL................................................................................. 41

Example of experiential learning 2) email communication ......................................................................... 42

Example of assignment with grading rubric ................................................................................................ 45

Example of peer-to-peer feedback and reflection note .............................................................................. 46

Student deliverables. Example 1: TBL tests ................................................................................................. 47

Student deliverables. Example 2: the effect of providing weekly feedback and giving weekly feedback

throughout the semester ............................................................................................................................ 47

F. Asking for feedback................................................................................................................................. 50

Testimonials about supervision ........................................................................................................................ 52

Note from Victoria S. N. Schrøder. .............................................................................................................. 52

Note from Anouck Jolicorps, ....................................................................................................................... 52

G. Testimonials about a collegial attitude and student feedbacks ............................................................. 53

Testimonial from Kristin Rygg, FSK .............................................................................................................. 53

Testimonial from Beate Sandvei, FSK, ......................................................................................................... 54

H. Evidence of student learning ................................................................................................................... 55

Extracts from student evaluations ............................................................................................................... 55

Correspondance with programme directors ............................................................................................... 56

Student testimonials (examples) ................................................................................................................. 56

Assessment from external examiners ......................................................................................................... 59

Students’ work as evidence of their learning .............................................................................................. 61

I. Dissemination ......................................................................................................................................... 61

J. Teaching online ....................................................................................................................................... 63

K. References cited in the teaching portfolio .............................................................................................. 64

4

1. Biography: My teaching history in a nutshell

My first teaching experience dates back to 2004, when, as an exchange student, I worked as a

student assistant “kollokvieleder” for the French section at NHH. The experience and the feedback were

so positive that I started teaching as a hobby. In China in 2004, I taught in a language school and in the

HQ of a company in Shanghai. In 2005-2006, in France, I taught French to exchange students in my

business school and took, at the same time, a bachelor specialisation in teaching French as a Foreign

language at La Sorbonne university in Paris (2006). In my first years in Norway (2006-2011), I worked

part-time as a French teacher in a high school, junior school, and full-time in a primary school. I also

worked at Folkeuniversitetet i Bergen (2006-2011), where I taught 5-6 courses a week and, at the most,

9. I also mentored new teachers.

My experience at university level dates back to 2010. At NHH, I taught half of FRA10 (bachelor

elective) and a mandatory translation course to master students in 2011 at UiB.

I started my PhD in 2011. Already from 2012, I had the co-responsibility to develop and teach a new

course in intercultural communication (VOA45). The course design was based on building intercultural

competence rather than an accumulation of knowledge. It was so innovative that the students chose it as

an example of best practice at NHH in 2014. Kristin Rygg and I presented our course philosophy and

design at a staff seminar. Later on, we published a book chapter together (Ly& Rygg, 2016) that reported

on the course's philosophy and design. At the same time, I also had a 30% position in a company and

taught cross-cultural management to employees in their subsidiaries in Norway, Sweden, Germany,

China and Korea. Though I was a PhD student, I held several guest lectures at NHH in bachelor and

master courses taught by colleagues at SOL, SAM and FSK. I also had a yearly guest lecture (2x 1,5h)

in the course Chinese Challenges between 2012 and 2014 (when the course was not offered anymore).

I received excellent student evaluations.

I have worked as an associate professor at FSK since 2017. Since then, I have been responsible

for 4 courses: 3 electives at the bachelor level (FRA10, FRA20 and FSK10) and 1 mandatory at the

master’s level for CEMS students (INB431, now CEMS402). These courses and their development are

described in detail in the following parts. During this short time frame, I have completely redesigned all

the courses to focus on students’ learning.

I have also held several guest lectures at NHH, NHH Executive, and other higher educational

institutions. Here again, with excellent evaluations

. I am currently preparing an NHH Executive module

on intercultural communication that will be interactive and online (to be taught in autumn 2021). I am

also working on a course package on intercultural communication and social integration for an NGO in

Bergen.

This teaching history shows that I have developed and taught various courses within my 17

years of teaching experience (for more details, see my detailed teaching CV

). I have also taught multiple

audiences and developed a range of methods and activities to adapt to my audience. I don’t use the same

activities to engage high school students and business students. At NHH, I engage my students with

different teaching methods, depending on the course and the level of study. My teaching experience

across departments and institutions and the

excellent evaluations attest to my teaching versatility and

adaptability. After the outbreak of the Covid19 pandemic in March 2020, all teaching has been moved

online. To best adapt to the new platform, I have read extensively and participated in seminars. I have

also had a continuous dialogue with and feedback from students. I share my reflections about online

teaching in part 10.

Since developing my knowledge and skills is of utmost importance to me, I regularly participate

in pedagogical courses and seminars. I have also attended more formal courses organised by NHH and

partner institutions

1

(Harvard, 2019) and have a bachelor specialisation in teaching French as a foreign

language (2006). I actively try out new teaching methods, conducting action-research (Biggs and Tang,

2011; Raaheim, 2013). This point will be illustrated in parts 3 and 4. I have applied deliberate practise

(Ericsson 2006) to my teaching. Instead of repeating the same mindless teaching year after year, I have

actively focused on improving performance through continuous reflection, experimentation and student

and peer feedback. I can, therefore, show a clear progression of my teaching over time. Besides, in the

1

The total number of hours of pedagogical training cumulates to over 200 hours, as desired by NHH

5

last few years, I have researched my teaching practice. This has resulted in several articles/book chapters

and conference presentations. These have allowed me to further reflect on my practice and apply the

learning I’ve drawn from reviews to polish my teaching.

I am currently supervising one PhD student and have mentored one new teacher at NHH. I was also

acting as PhD coordinator at FSK in spring 2020. My views on supervision and experience are detailed

in part 6.

2. Teaching philosophy

My teaching and learning views have evolved through the years, influenced by practice, courses and

readings, discussions with peers, and a reflective endeavour on my practice.

When I started in 2004, I believed that teachers were the source of knowledge, and lecturing

was the only way of transmitting it. My responsibility was to create the best possible lectures to motivate

students. Yet, my view has evolved since 2012, when I developed a course at NHH. In 2012/2013, I

attended two pedagogical courses that highlighted the importance of student-centred learning that I have

fully embraced. Now, I think that effective teaching is no longer about the transmission of knowledge.

Instead, it focuses on what the student does to learn and how the teacher can facilitate this process. The

evolution of my views is much in line with the three levels of teaching described by Biggs and Tang

(2011), from being focused on what the student is (level 1) and on what I, as a teacher was doing (level

2) in my first years of teaching to being focused on what the student does (level 3).

Since 2012, I have consciously and systematically tried to develop my courses' form and content

to support students’ learning most effectively. Two key elements have shaped my view. First, the

development of technology has changed the way students access knowledge (Serres, 2015) and let me

question my role: if all information is available within a few clicks, what is my added value as a teacher?

Second, my reflection is inspired by my research philosophy on intercultural interactions. Being

a fierce advocate of a constructivist theory on culture (Ly, 2016, 2019), I argue that cultural differences

are co-constructed in interaction. Transferring this idea that interactions are socially constructed into my

teaching practice is not a big step. Thus, my teaching philosophy is inspired by a constructivist view on

teaching and learning (Steffe and Gale, 1995; Vygotsky 1978, 1980), where learning is an active process

of knowledge construction. These two key elements have been a starting point for reflecting on my role

and the student’s role.

I believe that my role is to facilitate learning by engaging students to construct knowledge. On

that ground, I actively engage students by making them practise the discipline (2.1), providing them

with a safe and supportive environment (2.2), and creating a culture for feedback and reflection. (2.3).

2.1 Students learn by practicing the discipline

Lecturing alone mainly produces surface understanding but does not engage students (Biggs and Tang,

2011), who in turn do not fully grasp the complexity and the relevance of the topic. In line with Sweet

and Michaelsen (2012), who describe engagement as apprenticeship, I believe that students learn by

doing. I argue that NHH students should actively practice the discipline (be it global leadership or

French) to develop skills and reflect on their learnings to become responsible and reflected (global)

business practitioners.

Developing skills and competencies is an essential learning outcome in my courses, and I apply

two key theories: experiential learning (Kolb,1984) and transformative learning (Mezirow, 1997). Both

theories aim to trigger reflection and competency development. Kolb’s experiential learning cycle

involves four stages: (1) concrete learning, where the learner encounters a new experience or situation;

(2) reflective observation, where the learner reviews and reflects on their own experience; (3) abstract

conceptualisation, where the learner, who has learned from the experience, now gives rise to a new idea

or apply existing theoretical concepts to one’s experience to gain greater understanding; (4) active

experimentation, where the learner tries out the new idea or behaviour to see what happens. Effective

learning takes place when the student progresses through the cycle. Empirical studies show how

6

effective experiential learning, followed by guided interactions with faculty, is (e.g. Anthony & Garner,

2016; Caligiuri & Tarique, 2012; Lane et al., 2017; Mendenhall et al., 2020). As an analogy: one doesn’t

become a leader by reading a book about leadership, but rather by practising the discipline. I develop

how I implement experiential learning in my courses in the next parts.

Transformative learning is the “process of effecting change in a frame of reference” (Mezirow,

1997: 5), which are “the structures of assumptions through which we understand our experiences”

(op.cit.). Questioning one’s assumptions is a crucial aspect of transformational learning, as it helps

students develop awareness of the way they act and think. Activities such as group projects and

discussions, case studies and class simulations can trigger the process of transformative learning. Some

authors report using transformative learning to develop leadership skills successfully (Ensign, 2019; J.

S. Osland et al., 2017). I will detail how I use transformational leadership in the next parts.

2.2 Students learn in a safe and supportive environment

The practice of the discipline can only be successful if students can learn in a safe and supportive

environment. From an intellectual perspective, it means that new knowledge needs to be built in terms

of what students already understand. Inherent to the constructivist perspective on teaching and learning

is the idea that new knowledge is constructed through the lens of past knowledge and experiences. Recall

of prior learning is also one of the nine events of instruction described by Gagne (1965). Learning is a

game of building blocks where new knowledge is supported by an existing knowledge foundation. This

creates a manageable challenge for students that keep them motivated. For example, in my French

courses, I gradually increase the difficulty of activities and the assignments (see, for instance, the

assignments in FRA20 detailed in 4.1).

Learning in a safe and supportive environment also means taking the emotional point of view

seriously. For students to speak up (which is of utmost importance when practising a foreign language)

and express their thoughts and opinions (essential in global leadership), I create an environment of trust

and mutual respect. To build an enjoyable classroom climate (Biggs and Tang, 2011) and build rapport

among students, I facilitate activities to break the ice. For example, I introduced digital lunches in

autumn 2020 for students and me to get to know each other, despite the lockdown. As a student testifies:

“Annelise har også klart å skape et hyggelig miljø på zoom, hvor vi studenter har faktisk blitt kjent med

hverandre uten å ha møttes fysisk (...) Jeg personlig satte pris på de digitale lunsjene som ble arrangert

før undervisning”.

To build rapport between myself and the students, I rapidly learn the students' names so that

they feel valued and cared for. I also intentionally minimise the distance with the students, having small

talk with them. I communicate my expectations to the students about creating this environment at the

beginning and repeat this several times during the semester. Several studies (Clapper, 2010; Thomson

and Wheeler, 2010, among others) attest to the importance of creating an environment of trust and

mutual respect to enable students’ learning through active participation.

2.3 A culture for feedback and reflection.

Feedback is essential for learning. Positive feedback helps us appreciate what we do well and can repeat

it, while negative feedback helps us understand what can be improved. Feedback is also needed to

develop self-awareness. This has several implications for my teaching.

(1) Class activities with feedback.

I provide continuous formative feedback. For students to improve French, they need to practice and

receive feedback “on the spot”. As facilitator and expert, I use class time to give feedback and guide

students in their activities. In some of the activities, students review/correct each other

.

In the CEMS course, it goes further as feedback also comes from peers. Students work in teams (this

will be explained in 4.3) and give feedback to each team member every week. The feedback is

anonymized and sent to the students so that they can reflect on how they were perceived by their team

members and improve (experiential learning). I also comment on the feedback they give.

(2) Course approval and assignment forms.

7

I provide students with formative feedback on their course approval activities and assignments. In

French, for example, students need to hand in each written task twice. That is, instead of correcting their

papers (telling them the right answers), I indicate what type of mistakes they have made (preposition,

tense…). They need to hand in a corrected version to pass. In FSK10 and CEMS402, I provide extensive

feedback in a mentoring session with each group (about one hour per group). Here, I give feedback, help

them reflect and guide them in finding the right angle to tackle their reports (see testimonials from two

previous CEMS students in appendix).

In terms of assessment forms, I have a portfolio in 3 of the courses (FRA10, FSK10 and CEMS402). In

FRA20, we have an exam that tests their ability rather than their knowledge. This is further explained

in 4.1.

(3) Creating a culture for feedback and reflection also means that I also regularly ask students for

feedback.

End of the semester evaluations is a type of summative assessment that has some value. Still, it is more

efficient for teachers to have formative, ongoing feedback to change and grow. While I provide

continuous feedback, I also expect continuous feedback from students. I give them several arenas:

classroomscreen, oral feedback, Mentimeter, weekly reflection notes.

Feedback is integrated when

relevant and possible (writing workshop session in FRA20, guest lecture in INB431, more breaks when

teaching online in CEMS402).

For me, it is also essential to reflect and bring corrective actions when

necessary. As a student pointed out last week: “I also thought the Mentimeter was a good idea to get

more feedback of us students. I like how you demand feedback, and that you incorporate it into your

teaching (such as more breaks). That is really a great effort to make this course as enjoyable as possible

for everyone involved”. I highly value students’ feedback because they are on the front line and can

best tell me if what I implement contributes effectively to their learning. In the appendix, several students

and colleagues attest to my culture for feedback.

3. Reflections on own educational development

Here, I explain how my teaching philosophy has been translated into activities to engage students and

how they have developed over time. The changes that I have implemented aimed to contribute to a better

constructive alignment (Biggs, 2014) between learning outcomes, teaching activities and assessment

forms. I structure this part around the courses I teach at NHH and provide examples of changes in the

last five years.

3.1 FRA10: Fransk økonomisk språk and FRA20: Frankrike i dag: økonomi, samfunn og

kultur.

FRA10 is an elective for bachelor students who have learned French in secondary school and high

school, or equivalent. I have seen FRA10 from different perspectives: as a student assistant in 2004, a

part-time lecturer in 2010 and an external examiner in 2010 and 2016. I have been responsible for the

course since 2017.

Traditionally, the primary learning outcome of the course was the repetition of French grammar.

The teaching method consisted of lectures, and the final assignment consisted of grammar exercises,

graded pass/fail. This type of teaching corresponds to the traditional teaching form and the view that

grammatical competence is central in foreign language learning (as explained by Bax, 2003). In 2010, I

taught half of the course and received excellent student evaluations. We, the teachers, were enthusiastic

and competent, and the students were highly motivated. In hindsight, however, these thoughts were an

example of traditional teaching focusing on what the student is and what the teacher does (Biggs and

Tang, 2011).

As the course responsible in 2017, I wanted to shift the learning outcome to develop the

students’ ability to communicate in professional settings. In class, I would lecture for about 15 minutes

and then students would work on application activities. At home, they could practise further with

exercises that I created on Canvas. Course approval consisted of three grammar tests to pass. The

8

students had to take a school exam that consisted of grammar exercises and a short essay. Student

evaluations were very good (4.47/5). However, I thought that I could increase student learning by

eliminating the one-size-fits-all lecture. This was to adapt to the heterogeneous student group: some are

fluent while most have French from high school. In 2017, I attended a pedagogical seminar at NHH and

heard about flipped classrooms. This was very inspiring, and I read extensively on the method and how

it has been implemented in languages courses (Basal, 2015; Bergmann and Sams, 2012; Correa, 2015;

Muldrow, 2013).

I redesigned the course in 2018 using the flipped classroom method. The LOs were roughly the

same, but I now implemented a teaching method and activities aligned with these LOs. I focused on

what the student does in class (level 3 in Biggs and Tang, 2011). The ability to speak and to understand

French has become the primary goal, and grammar becomes a tool, not an end in itself. Instead of being

the lecturer, I am a facilitator and an expert (Vygotsky, 1978). I walk around, give individual feedback,

answer questions along the way, and give more challenging or more manageable tasks to students who

need it. Student evaluations are excellent (H18: 4.80/5; H19: 4.22; H20:4.9). Students praise the teaching

method that allows everyone to practise the language in a safe environment and gives room for

individualised learning: “Selve klasseromsundervisningen fungerte veldig bra. Det er bra at alle aktivt

inkluderes og oppfordres til å delta muntlig” and “Det var også veldig fint at man kunne spørre om

ekstraoppgaver om man trengte det”. The assignment was a school exam. The quality of the exam

answers attests to the method's effectiveness (see external examiner’s testimonial

) and that the students

have reached a deep approach to learning.

It takes, however, a couple of years to evaluate and polish the teaching method. After 2018, I

have modified three things: 1) Assessment form and content: I have changed the assessment to a

portfolio that consists of 5 tasks, 3 written and 2 oral ones. Students are now assessed on their

communication skills (oral and written), and it makes no sense to give them a school exam based on

grammar. This change in the assessment form allows for a constructive alignment between the LOs, the

class activities and the assignment. See 4.1.

2) Homework: it is easy to take for granted that students do their homework. Yet, if they don’t, the

method is not effective. Now, I build all my lessons based on the homework.

3) More meta-communication on my teaching philosophy and methods: as students are not familiar with

the method, I take time to explain what the method consists of and how it is beneficial for their learning.

When students understand the method, they appreciate it even more: “Det fungerte veldig bra med

flipped classroom som stiller krav til forberedelse og lekser før timene. Videre fungerte det bra å sette

en standard om at alle skal ha på kamera og delta aktivt i timen fra start.” At the end of each class, I

also “wrap up” the learning (tips from my course in Harvard). This is very important because students

who learn with active methods may be less aware of their learnings (Deslauriers et al., 2019).

FRA20 is the module that students can take after FRA10. It is a new course that I created and

implemented in 2019. To create the course, I discussed existing best practices with colleagues at FSK,

ensured relevance by talking to businesspeople and invited former students of French to share their

feedback on the existing courses. I crafted FRA20 using this feedback extensively. The main LOs are

for students to acquire knowledge on business culture and current issues in France and competencies to

understand news in French and express and argue for their opinions, both orally and in writing. I also

use the flipped classroom method. Students work with tasks (see 4.1) that are of gradual difficulty as

course approval to ensure a clear progression over time. Each written task is commented on extensively

and sent back to the student for review/correction. Giving formative feedback to students have increased

performance (see student’s work provided in appendix

). Students’ continuous feedback has played an

essential role in adapting activities that would contribute best to their learnings. I introduced changes

when relevant: for instance, some students wanted more guidance when writing, so I organised a

workshop where students worked on one of their tasks with guidance. The student evaluations are

excellent (V19: 5/5, 94% response rate; 4.80/5 for relevance).

Students’ testimonials and the external

examiner assessment confirm that the students have learned a lot after these two courses.

3.2. FSK10: East Asian culture and communication

9

FSK10 is a bachelor elective. Together with Kristin Rygg, I created this course in 2012 to respond to

students ‘wish to learn about East Asian culture

2

. Many courses in intercultural communication teach

and assess students based on the accumulation of knowledge about different cultures. Yet, both

researchers in the field, we believe that intercultural communication needs to be experienced and

reflected upon to develop competence. Our challenge back then was that little had been published in the

field to suggest other ways of teaching (Blasco 2009; Szudlarek, Mcnett, Romani &Lane, 2013). Before

the course, we attended a case study seminar (2012) that inspired us. In the first year (2012), we taught

the course using case studies, guest lectures and traditional lectures, with a final school exam that

assessed the student's knowledge. Again, it took us a couple of years to reflect on and polish the course.

But from the start, Kristin and I prepared and taught the course together and were present in all the

classes. This gave us the chance to observe each other’s classes, provide extensive feedback, try out new

activities and, in the end, improve both our teaching and our vision of the course. In other words, we

conducted action-research as advocated by Biggs and Tang (2011) and Raaheim (2013).

We redesigned the course in 2014 and reformulated the LOs more clearly, focusing on students’

development of intercultural competence. We used different teaching activities that complemented each

other well and contributed to reaching the LOs: case studies allow students to dissect and discuss

business situations; role-plays enable them to get in someone else’s shoes to understand their

perspective; and personal reflection allows them to reflect on past behaviours and make hypotheses

(Helyer, 2015; Kolb, 1984; McGuire, Lay, & Peters, 2009). These teaching activities allow students to

learn by doing (2.1) in a safe and supportive environment (2.2). We also changed the assessment form

to a portfolio. In 2014, students elected FSK10 as an example of best practice and the teaching method

was presented at a pedagogical seminar at NHH. Subsequently, Kristin and I published a book chapter

Ly & Rygg, 2016). The book entitled Intercultural competence in Education: Alternative approaches

for different times wishes to promote a renewed approach to teaching intercultural communication. Our

chapter featured in this book shows how our course's teaching was innovative in the field. Writing a

research piece also helped us refine our reflection and further develop the course (based on the reviews

we received). Our pedagogical development has brought more changes to the course, again supporting

students’ learning. Since 2018, we have offered more formative feedback on the assignments. (1)

Fieldwork project: instead of presenting orally their results, receiving quick oral comments from us and

handing in a written report, we now provide a full hour mentoring session with each group. (2)

Reflection paper: one of our main LOs and challenges was to make students critically reflect on their

values. We have tried different activities, with mixed results. Since 2018, we have implemented a

weekly reflection note. I detail these activities in 4.2.

3.3. INB431/ CEMS402: Global leadership practice

INB431 (CEMS402 since 2021) is a mandatory master course restricted to CEMS and taught in all 34

CEMS institutions. I held a guest lecture in 2014 and have been responsible for the course since 2018.

In 2018, I taught the course in an intensive format (two full days of lectures x3) due to maternity

leave. I used case studies. After analysing and discussing the cases, I would give a short lecture (about

30 min out of a 6-hour session) to ensure that all students understood the theories. I also invited two

business executives for guest lectures. The student evaluations were not as good as I am used to.

Students liked the case study approach. However, some also pointed out that: 1) lectures were

unnecessary and 2) the course could be more interactive 3) the course was perceived as easy.

I could have blamed it on my maternity leave and that it was a new course for me, but I instead took it

as a learning opportunity. Why didn’t the teaching method from FSK10 work here? The short answer is

that the student group is different. The students are mainly international students from the CEMS

network. They are highly international, and many are multicultural. They have some years of work

experience. However, as I have found out, about half of the group has already taken a similar course.

This is a balancing exercise for a mandatory course: how can I teach an advanced course when half the

class doesn’t know the basics? And how, when doing so, can I maintain the attention of the other half?

2

Student survey conducted in 2011

10

So, the first lesson was to get to know my audience. Since 2019, I have emailed the students before the

course start, asking them information about, among others, backgrounds, international experience, and

whether they have had a similar course in their curriculum.

Despite these challenges, this heterogeneous student group also provides valuable opportunities.

First, I can use the class diversity to illustrate different world views. Instead of lecturing or working on

a case study on multicultural teams, I can actively use this diversity and assign the students to

multicultural teams to let them experience and reflect on the challenges in such settings (experiential

and transformative learning). Second, since some students have prior knowledge of some of the topics

presented, they can explain concepts to the other students. When students teach their peers, they need

to reformulate their knowledge and gain a deeper understanding of these topics (Biggs and Tang, 2011).

These opportunities lay the groundwork for more student dialogue and collaborative learning.

Once more, I investigated new teaching methods that would allow me to teach this course in the

best possible way for student learning. I attended a seminar at NHH on Team-Based Learning (TBL)

(autumn 2018) that inspired me. I redesigned the whole course using TBL in 2019. I implemented new

LOs with a greater emphasis on developing global leadership skills. The teaching format was also

changed to a weekly 4hour lecture.

Students have regularly provided feedback on the course activities, and I also organised a

student panel in 2020 to receive suggestions when the course was to be changed (and became

CEMS402). I have actively used their feedback, as mentioned in 2.3, but I have adapted activities to my

teaching philosophy: for instance, the students wanted to have more guest lectures. I invited business

executives, but instead of the usual monologue, I designed interviews and case studies. I detail these in

5. I have polished the activities and assignments every year. Students in spring 2021 are very satisfied

with the course so far, as attested by the academic director and extracts from the students’ reflections

.

To sum up, in the past few years, I have redesigned the four courses I teach. These changes

aimed to contribute to student learning and align the LOs, the class activities and the assessment forms.

These changes are based on my evaluation and reflections, students’ feedback, and my increasing

knowledge of teaching methods supporting student learning. My approach is explorative, and I conduct

action-research (Raaheim, 2013). The courses now clearly allow students to take charge of their learning

(level 3, Biggs and Tang, 2011). I describe how in the next part.

4. Teaching and assessment repertoire

4.1 FRA10 and FRA20

Main learning outcomes

FRA10

Teaching method and

activities

Assessment methods

(1) Give oral presentations

using business French

vocabulary

(2) Express one’s opinion

in a professional

setting

(3) Produce written

documents that are

usual in professional

settings, using relevant

business terminology

Flipped classroom

Homework: readings or video

on a grammatical point and

simple application exercises

In class: application activities

that take the homework as a

starting point. Practice (oral

comprehension, speaking

activity, role play…).

See appendix

Requirement for course

approval: grammar quiz on

canvas (unlimited trials, but

need to get 30/40 to pass)

Assessment: A portfolio

composed of 3 written and 2

oral tasks. Each written task is

commented on and needs to be

handed in back with

corrections to be approved

Grading: pass/fail

Main learning outcomes

FRA20

Teaching method and

activities

Assessment methods

11

(1) Knowledge of French

economy, society and

culture that are

important to

understand France

today

(2) Ability to understand

news in French (both

oral and written) and

hold a presentation on

these topics

(3) Ability to write

structured documents

relevant to the

workplace

Flipped classroom

Homework: readings or videos

on the topic and vocabulary

exercise.

In class: application activities

that take the homework as a

starting point and further

practise of the language (oral

comprehension, oral

presentation to peers, writing

workshop…)

See appendix

Requirement for course

approval:

3 written and 2 oral tasks. Each

written task is commented on

and needs to be handed with

corrections to be approved

Assessment

1 school written exam (50%)

1 oral exam (50%)

Grading A-F

The flipped classroom method gives students the possibility to learn at their own pace. They study

theory/grammar by reading or watching a short video and doing easy applications exercises as

homework. In class, they practise and deepen the knowledge learned at home through different activities

.

First, they are briefly tested on the knowledge learned (e.g., easy application exercise, quiz); then, they

watch videos or listen to dialogues (LO1 of FRA20); they answer comprehension questions in small

groups (LO3 of FRA10 &FRA20), using the new vocabulary or grammar learned at home. Last, they

conduct activities like role-plays

or topic discussions to practice further and become independent users

of the language (LO1&LO2 of FRA10, LO2 of FRA20). As students work a lot in small groups, they

speak a lot of French. As a facilitator, I can give them adapted activities, and as an expert (Vygotsky,

1978), I offer guidance and explanations when needed. There is also collaborative learning in class:

those with a higher command of French can explain concepts and correct other students. By doing so,

they also gain a deeper understanding of the language (Biggs and Tang, 2011). These activities are in

line with the LOs.

For course approval in FRA10, they need to complete a grammar quiz. They can try as many times as

they want until a set deadline but need to have at least30/40 correct answers. I have created a set of

about 300 questions on Canvas, so questions change every time. As final assessment, they have a

portfolio consisting of 3 written and 2 oral tasks. I comment on each written task.

I highlight the

mistakes, explain what type it is (preposition, expression, tense…) and send it back for correction. I

approve the task only if the new version reaches a level corresponding to a C grade. Students also receive

formative feedback on their 2 oral tasks (what they are good at, points to improve and how).

For the course approval in FRA20, they hand in 3 written tasks and two oral ones, with gradual difficulty

and with the same commenting/correcting system. In the first written task, students answer questions

based on a newspaper article and write short answers

(100-150 words); in the second one, they are

individually coached to write a structured essay (500 words) (LO3 of FRA20), and in the third one, they

write a structured paper without help (500 words). For the oral tasks, they need to comment on a short

newspaper article. The first time for 10 minutes with 10 minutes of preparation, the second time for 20

minutes with 30 minutes of preparation.

Gradual difficulty participates in the building blocks (see Gagne

1965) of knowledge explained in 2.2. The final assessment is an oral exam and a written school exam

that count for 50% each. The exams in FRA20 are not a surprise as students work on a task they have

previously practised during the semester. In the written part, they need to read a newspaper article,

answer a few questions and write a 500 words essay based on the topic. The oral exam consists of a

presentation based on a newspaper article. The exam lasts 20 minutes (with 30 minutes of preparation).

4.2 FSK10

12

Main learning outcomes

FSK10

Teaching method and

activities

Assessment methods

(1) knowledge of relevant

theories related to

intercultural business

communication

(2) skills: ability to reflect

on the values

underlying behaviour

and communication in

East Asia

(3) ability to critically

assess the theories

related to intercultural

business

communication

Case studies presented in a

bottom-up way (case first and

then theory)

Role plays- experiential

activities

Reflection activities and

weekly reflection notes.

Mentoring session after

fieldwork presentation

See appendix

Requirement for course

approval:

75% attendance

Oral presentation and

discussion of peers’

presentation

Assessment: portfolio

consisting of:

1) an individual reflection

paper (50%), 2) a group report

based on fieldwork (ca. 50%)

In FSK10, students work on case studies with a “bottom-up” approach (Holliday, 2012). An example of

case teaching is provided in appendix

. “Bottom-up” means that they start looking at the problem,

sometimes have a role-play to get into one of the protagonists’ shoes and reflect on the underlying values

at stake (LO2). We have this approach, so students do not frame their understanding of a problem

through the lens of a specific theory but in a holistic way. After the discussion, we have a short lecture

that presents the theory (LO1). As reality is more complicated than what theory says, it helps students

assess critically existing theories (LO3). Students write a brief reflection note at the end of each class

where they jot down

immediate thoughts related to the topic. Writing or using journals can help students

engage in their learning, develop their self-awareness, and rethink their conceptualisation of the world

(Cunliffe, 2004) (transformational learning),

which in turn helps them to better reflect on LO2 and

nuance theories (LO3). As intercultural competence takes time to be practised and developed, we believe

in a portfolio assessment with formative feedback. The portfolio consists of a group fieldwork project

(expert interview) and an individual reflection paper. The group project allows students to draw on

theories and apply them to an informant’s case (LO1) and critically discuss these theories (LO3). They

also need to interpret events from an East Asian perspective (LO2). To help them in the process, we

provide a full hour of mentoring for each group. This mentoring session also provides a supportive

environment ( see student testimonial

). Students also need to hand in an individual reflection paper and

assess it to theories (LO1, LO2 and LO3). Again, I believe the LOs, the class activities and portfolio

assignment are now constructively aligned.

4.3. CEMS402

Main learning outcomes

CEMS402

Teaching method and

activities

Assessment methods

3 competencies to de

developed:

(1) Demonstrate self-awareness

LO1: Enhanced ability to

describe their own culture and

question the way they act or

think

(2)

Communicate effectively

when working in an

international environment

Team-Based Learning (TBL)

I form teams of 5-6 students

that are heterogeneous

(different backgrounds) and are

permanent throughout the

semester (LO2)

Homework: readings (LO4)

In class:

Requirement for course

approval:

75% class attendance (physical

or online) and 75% of peer

feedback completed

Assessment:

A portfolio consisting of

(1) Presentation of the

fieldwork results and

13

LO2: Enhanced ability to

communicate effectively in

multicultural teams

LO3: Enhanced ability to give

constructive feedback in a

cross-cultural context

3) Think critically

LO4: Enhanced knowledge of

the main theories relating to

cross-cultural

management/global leadership

LO5: The ability to critically

assess the main theories related

to cross-cultural management

and their usefulness for the

global worker and manager

- individual multiple

choice question test

(LO4)

- team test: same test,

but in their respective

team. (LO4)

- Application activities:

case, dilemmas,

discussions… (LO1,

LO2, LO4, LO5)

- Weekly peer to peer

feedback (LO3)

- Reflection note at the

end of each session

(LO1)

Mentoring session after the

fieldwork (LO4 & LO5)

See appendix

discussion of another

group's fieldwork

presentation (20%)

(2) Results of weekly tests

(20%)

(3) Feedback- quality of

the weekly feedback

given (20%)

(4) Written group report

based on the fieldwork

project (20%)

(5) Individual reflection

paper (20%)

Overall, the teaching method is inspired by TBL (Sweets and Michaelsen, 2008). It is an instruction

method that fosters student-centred learning and student accountability. TBL is composed of fixed

elements that are repeated in every session. At the beginning of the semester, I form teams that are

carefully designed to blend at least four different nationalities, different international experiences,

previous work experience and consideration of gender. These teams remain permanent during the

semester. Before class, students are assigned readings that give them knowledge about cross-cultural

management/global leadership (LO4). In class, they first complete an individual test

that ensures that

the learning is understood (LO4). Then, in their groups, they compare and discuss the answers (LO2).

They explain their reasoning if they disagree. This stage is essential for peer learning and provides the

student with a deeper understanding of concepts (LO4 and LO2). Then they submit their answers. The

remaining class time is devoted to applications activities (as

live case studies or experiential activities)

that help them deepen and critically assess theories (LO5). After each session, they write a reflection

note (LO1) and provide

feedback to all team members (LO3). Thus, in addition to the knowledge on

specific topics, students use TBL as a semester-long experiential activity on teamwork.

My method differs slightly from TBL in two points, and these are for pedagogical reasons. The

written appeal is not used. Instead, students raise questions directly, share their reasoning and discuss

concepts in class. This step allows students to achieve a higher-order level of thinking in Bloom’s

taxonomy (Biggs & Tang, 2011). Second, feedback is used differently. In TBL, feedback counts toward

the final grade and is only distributed midterm and end-term. In my course, feedback received does not

count towards the final grade. Personal development is crucial, and students learn by continuously

reflecting on and trying to improve their behaviour. By doing so, students can try and test and make

mistakes.

Students learn how to provide constructive feedback at the beginning of the semester: they read relevant

literature, discuss the topic in class in their teams, and practise every week. They fill in an online form

in which they detail both the positive contribution and improvement points of each peer. I review and

send the received feedback to each student as a formative assessment. In class, I discuss examples of

both good and offensive feedback, which allows them to reflect on, test and improve their feedback

giving skills. The feedback given (LO3) counts for 20% of the final grade. They receive formative

feedback on their feedback given.

The assessment consists of a portfolio with 5 elements. The presentation of fieldwork and

discussion test LO2, LO4 and LO5; the weekly tests LO4; the feedback given LO3; the group report

LO2, LO4 and LO5 and the individual reflection paper

LO1. There is, therefore, a constructive

alignment between the LOs, the teaching activities and the assessment tasks.

14

5. Pedagogical materials

I have designed the course curriculum of the four courses I am responsible for. In FRA10, I use a

textbook complemented by material that I have created. In the three other courses, I have designed the

pedagogical material myself. These include, among others:

Role-plays: they give students the possibility to practise the language in professional settings. They can

actively use the vocabulary and expressions learned to become independent users of the language. I have

designed several role-plays, such as the one presented in the appendix

. Here, students are in a business

meeting and need to express and defend their opinions about selling a product/ proposing new products.

Activity packages: I have created activities to learn about facts about France actively: students are

divided into groups of 3-4 and work with a given topic

. In groups, they start by answering a few

questions that draw on their previous knowledge (2.2) about the topic and practise French in a safe

environment (2.1 and 2.2); then, they watch a short video and answer questions. This activity allows

them to draw on their listening and speaking skills. After 20 min, work on a new topic. Since the topics

are the most current ones, I regularly create new packages.

Experiential activities in class: In CEMS402, I assign a team leader each week

. Since the goal of this

course is to develop leadership skills, students can plan and implement their roles. After the session,

they receive peer feedback and write a reflection note to reflect on their improvement points. Such

activity is highly effective in developing leadership skills, as the literature shows (Caligiuri &Tarique,

2012; Mendenhall, 2020).

Another experiential activity is the analysis of emails. I analyse how they open their emails (how formal

they are) and show them my analysis in class. We discuss the findings, and I show then a survey I have

conducted that reports on how their emails can be perceived among international professionals. This

activity is an eye-opener for many and an activity that has a higher impact than a lecture on how to

effectively write professional emails

Guest lectures: Though students usually like when guest lecturers share their business insights in class,

they, too often, just lecture. Students hear a nice story, but they remain passive. To engage students, I

have developed two main activities:

- Interview: Before the class, I ask students to check the company’s activity and/or the guest’s

profile (on Linked In, for example). Then, they create a questionnaire

and interview the guest.

Students are engaged and can ask questions they actually think are relevant, and guest lecturers

also find the experience rewarding. I was inspired by Raaheim 2013 for this activity.

- Live case study: students are presented with a case by a guest lecturer on which they work on.

They then discover that the case is actually the experience/ the challenges of the guest lecturer.

See the appendix for an explanation of the case

.

Have I completely stopped lecturing? For the most part, yes. It would be more precise to say that instead

of lecturing as a default way of teaching, I use lecturing for very specific points. Sometimes, after their

readings at home, students have follow-up questions or a matter that needs to be clarified. Then I provide

a short lecture, but I include a form of active participation (short quiz on Mentimeter, 3-2-1 activity, pair

and share…).

As for future development: I see pedagogical development as a continuous process and aim to continue

creating new activities to foster active learning. I am currently planning several projects: 1) with

colleagues from the CEMS network, we are working on creating a common case study involving several

cultures 2) I am part of a lecture hop-in initiative with the Association for Business Communication. As

online teaching has become common, we can share our expertise across institutions through a short

15

lecture or short exercise and 3) I am currently working on another live case for the CEMS course (to be

ready by April).

6. Supervision

I supervise one PhD student, Victoria S.N. Schrøder

(main supervisor). To describe my philosophy

about supervision, I like to use the Norwegian word “veiledning”. Unlike the English term that implies

that the supervisor “looks over” (from its etymology), “veiledning” has the idea that the supervisor

“shows the way”. My role is to guide, as an expert and in a Socratic way (Vygotsky, 1978). In addition

to completing her PhD thesis, I think that my role is to help her build a good academic CV. Therefore,

I am mentoring her also in teaching. Inspired by the mentorship system developed at Harvard, I have

set up a program for her to develop her teaching skills: she has observed some of my colleagues and my

classes, and we have discussed my teaching philosophy. She has taught several classes, and at the

beginning, I followed her teaching and gave her feedback. Today, we still regularly share ideas and

discuss teaching plans.

Since 2018, I have also informally mentored Anouck Jolicorps, a lecturer in French at NHH. This

mentoring included working together with her teaching plans and activities (particularly at the

beginning), class observation, weekly discussion before and after each class, sharing best practices and

working together with the feedback and grading system. Though she is an experienced teacher, we still

regularly discuss teaching plans and ideas. In mentoring situations, I try to create a safe working

environment to foster collaboration and feedback. To do so, I insist on the importance of meta-

communication.

Both Anouck and Victoria attest to how I openly discuss best practices and value their feedback, as well

as students’ feedback.

In April 2019, I attended a seminar on supervision. This has also given me essential insights on the role

of meta-communication and on the importance of discussing mutual expectations (see Victoria’s report

on the expectation questionnaire)

7. Teaching planning and contributions in FSK and NHH

I have experience with course design at NHH. FSK10, FRA20 and CEMS402 have been

designed and implemented from scratch. FRA10 and INB431 have been completely redesigned for

learning outcomes, teaching activities and assignment forms. Therefore, I am familiar with

administrative tasks related to pedagogy, such as working on a course description, defining learning

outcomes, and calculating student workload and its conversion to ECTS points.

I have, in addition, co-organised two PhD courses: Transferable skills: Research

Communication and Career Planning (2016) and Language management (2019).

In planning these courses, I have collaborated closely with colleagues at FSK. I have extensively

worked with Kristin Rygg

(co-course responsible) in the planning, development, implementation and

teaching of FSK10. As stated above, one of the specificities of our teaching has been to plan and teach

the whole course together. When planning FRA20, I have extensively exchanged ideas and best

practices with colleagues at FSK (see the testimonial by

Beate Sandvei). This provided common learning

outcomes and assignment forms for the two new courses launched in 2019 (FRA20 and SPA20). To

ensure the relevance of the courses I teach, I also consider feedback from the industry.

I highly involve students in teaching planning. For FRA20, I have invited former students of the

French courses to provide me with feedback and took their suggestions into account. In the planning of

CEMS402, I also involved former students by inviting them to a panel. We openly exchange about what

worked well, what could be improved, and they shared their suggestions. My openness and receptivity

to feedback are in line with my teaching philosophy. Positive feedback is a good indication that what I

do contributes to student learning. I use negative feedback as a learning opportunity and a possibility to

grow as a teacher. I am also accountable to these students who take their time to share their insights with

16

me and make sure to tell them if/how I have taken their feedbacks into account. This is, for instance,

mentioned in a student’s testimonial, who join the feedback panels both for FRA20 and CEMS402.

In addition to informal exchanges with colleagues, I have held several presentations and lunch

seminars at the department:

- Presentations of FSK10 (2016) and FRA20 (2019) at the strategy seminar of FSK

- Regular participation in pedagogical lunch seminars at the department (Use of Mentimeter,

Edword, Experiences after my stay at Harvard)

At NHH, I recently presented my experience in teaching online using the flipped classroom method in

a pedagogical seminar

(autumn 2020). In 2019 I was also responsible and facilitated a case during the

welcome week (about 100 students). As mentioned above, I have also presented FSK10 (then VOA45)

in a staff seminar in 2014 as an example of best practice.

At NHH, it is also essential to attract new students, and the way we communicate our research to

potential new students is crucial. I have also been active on this front and made a video for Åpen dag

(2020) to promote intercultural communication to high school pupils. Also, together with colleagues at

FSK, we organised Forskningsdagene in 2016, explaining our research to pupils. I have also had several

similar activities at UiB previously.

Other institutions:

- Member of the Global Leadership Practice CEMS faculty

. We meet once a year to share best

practices in teaching the CEMS course.

- Member of the research group VAKE (Values and Knowledge Education) at NLA. VAKE is a

teaching method that is grounded on a constructivist view of cognitive and ethical development.

The research group offers a platform for discussion and sharing of best practices in teaching

such dilemmas.

- Member of the Association for Business Communication; sitting at the publication board (2020-

2022). We share good practice through seminars across institutions and have implemented a

hop in lecture scheme.

8. Dissemination

In the last few years, my teaching has also been an object of research. I have written 5 peer-reviewed

articles/book chapters related to my teaching. 3 of them are expected to be published in the fall 2021/

spring of 2022. See the appendix for the title and the topics of the articles.

The paper that reports on using TBL to develop global leadership skills (forthcoming Oct/Nov 2021)

has been qualified as a “wonderful paper (that) will be extremely useful for other global leadership

professors” by the lead editor of the journal Advances of Global leadership, Joyce Osland.

I have presented reflections or activities linked to my teaching in 2 international conferences (see

appendix). In October 2020, at the Annual ABC conference, I had a presentation in a panel on Learning

and Teaching, where I reflected and deconstructed my practice and discussed how the instructor and

students negotiated their identities in the classroom. At the beginning of March, I will present a

workshop on teaching leadership using TBL at the Team-Based Learning Collaborative conference.

This workshop will be co-presented with Judith Ainsworth from Mc Gill University in Canada. I had a

third conference paper about teaching French using flipped classroom method, but the conference was

cancelled because of Covid 19.

Writing research papers and presenting at conferences have helped me reflect on my practice and

actually become a better teacher. Through the comments from the reviewers, I have spelled out the

specificities of my courses; some of the learning outcomes become clearer; and I have questioned and

redesigned activities or assessment that I have then implemented in my teaching.

17

I have shared my reflections and best practices in talks and interviews. Recent ones include: 1) a Podcast

for NOKUT-podden – En podcast om høyere utdanning som skal bidra til samtalen om god praksis i

høyere utdanning – where I share my reflections after one year of teaching online. (To be aired in mid-

March 2020); 2) An interview in Khrono Slik lager hun et godt studiemiljø via Zoom (24.01.21) where

I share my tips to engage students online. To date, it has been shared 238 times (Source Retriever) and

3) An interview in Paraplyen “Focus on people, not on technology” by Astri Kamsvåg. I have also

written posts and articles on Linked In.

These papers, collaborations and examples of dissemination attest of my scholarship of teaching and

learning.

Further plans (As of 01.03.21): (1) I have sent a workshop proposal at the ABC conference 2021 (with

J.Ainsworth) It is entitled: Developing Competencies for Communicating and Working Across Cultures

in the Classroom: A Team-Based Learning Approach. (2) I have just interviewed by 2 journalists on my

approach to teaching leadership. (3) I have a kick-off meeting tomorrow with colleagues from 6 other

institutions to apply for funding for a call on Education and Democracy for Horizon 2022.

9. Evidence of student learning

Student learning can be assessed in different ways. Alone, they provide an insight on the teaching. Yet,

taken together, these qualitative and quantitative elements offer triangulation that attests to student

learning. In addition to my own assessment above, I can refer to:

9.1. Student evaluations

The evaluations oscillate between very good and excellent (source Bluera)

FRA10

(H18): 4.8/5; (H19): 4.22; (H20):4.90.

FRA20

(V19): 5 (88% response rate)

FSK10

(H18): 5; (H19): 4.73

INB431

(V19:4.00); (V20):4.40. Students in V 21 are so far very happy with the course, as

attested by students’ reflection papers and emails

9.2. Emails from programme directors

My teaching is qualified as “knallgod”, “strålende bidrag” and “veldig positive til ditt kurs”. These can

be found in the appendix

.

9.3. Student testimonials

Some students have written me emails after the exam to tell me how much they have learned and how

much they have appreciated my teaching. A few quotes are provided here.

Full assessments can be found

in appendix. About the French courses : “jeg er overrasket over hvor omfattende læringsutbytte jeg

synes jeg fikk», «jeg var fornøyd med utbytte jeg fikk fra kursene siden jeg føler at fransken min ble

forbedret både skriftlig og muntlig», «det siste året har jeg lært mer enn jeg gjorde på 5 år fra

ungdomskole til videregående skole».

About the CEMS course: “I liked the course and I gained a lot

from it”; “Now I've started to realize the value of the class and it is changing me on a weekly basis. I

really appreciate what is given by the class and would like to express my gratitude again!”

9.4. Assessments by external examiners

18

The two external examiners praise the assessment methods and high quality of the students:

“imponerende høy kvalitet” (FRA10 and FRA20) and “ I have witnessed such learning in the reflection

pieces produced by most students” (INB431/CEMS). Their full assessment is in appendix.

9.5 Students’ work

I show 3 examples of student learning. 1) I show how a student in FRA20 has increased his ability to

produce structured text in a very good French. We can see that comments are fewer and fewer throughout

the semester, despite the increasing difficulty of the tasks. We can also see that the second version of

the hands-in is almost perfect. This clear progression attests to his learning. 2) I show how students in

CEMS have learned and understood theories. I refer to 4 weeks of TBL group tests, where scores for all

6 teams oscillate between 40/40 and 38/40. 3) I show how the weekly feedback provided throughout the

semester in the CEMS course has changed these students. I also show how a student has increased his

ability to write feedback: at the start of the semester, feedback is vague, while at the end, he can pinpoint

specific positive contributions and areas of improvement. This highlights how giving and receiving

regular and detailed feedback can lead to effective learning and behavioural change.

10. Conclusion: a few reflections on online teaching

I’ve taught online for a year now and have done so successfully. I will conclude with a few reflections

about contributing to student learning behind the screen. Without the physical classroom, it has been

more challenging to engage students. Yet, I believe that it is not impossible, and my experience confirms

so. I have learned new tools and used them extensively (such as break out rooms in Zoom); I have

simplified access to information on Canvas

; I use even more metalanguage about what I do. I believe I

have successfully transferred my teaching philosophy into digital learning activities to engage students.

With break out rooms, students learn by practising the discipline (2.1).

I have implemented virtual

lunches to build rapport with the students and created a friendly atmosphere.

I don’t make a fuzz about

my video background, which lowers the threshold for students to have their cameras on and be active. I

have built connectivity over content: connectivity between the teacher and the students, but also among

the students themselves (Anand, 2016), participating in maintaining a safe and supportive environment

(2.2). I continue to guide and provide extensive feedback on students’ work (2.3) to learn as effectively

as possible. More importantly, I regularly ask for feedback (2.3) and reflect, experiment online and

improve student learning. I have recently shared my reflections and tips with colleagues at NHH

(pedagogical seminar) and in interviews and podcasts. Students’ comments about online teaching and

learning have been overwhelmingly positive: “what I've learned outweighed my expectations. I really

liked the breakout room activities but also the feeling of freedom and understanding during the course.

I also felt much more included in the "lecture" than during comparable courses previously. The most

important learning outcome from today is, in my opinion, realising, that online lectures can be even

more effective than casual classes. » (V21). I don’t record my sessions since class time is devoted to

discussions. Yet, class attendance has been high despite the pandemic. According to the following

comment, one may even wonder whether my classes can actually give a sense of normality: “I en tid

hvor hverdag ikke er det samme som det en gang var, så har det vært betryggende og behagelig å ha

dette faste holdepunktet to ganger i uken.» Many students have praised my humanised approach to

teaching (Khan, 2011). Most importantly, I have shown that I deeply care for the students. I will end

this self-assessment with a student statement: «Da lockdown ble innført i Norge i mars 2020 ( …) Hun

var også den eneste foreleseren som spurte hvordan det gikk med oss før vi startet videosamtaler. Denne

tiden var vanskelig for mange, og Annelises tilpasningsdyktighet og ikke minst medfølelse bidro til at vi

fikk fullført kurset og semesteret på et relativt normalt vis».

19

11. Appendices

A. Teaching CV

Teaching affiliations and course responsibilities

07/2017- present:

Associate professor (FSK), NHH

Course responsible of:

FRA10: French language for economics (elective, bachelor)

FRA20: France today: economy, society and culture (elective, bachelor)

FSK10 (VOA045): East Asian culture and communication (elective, bachelor)

CEMS402: Global leadership practice (mandatory, master, CEMS)/ formerly INB431 Global

management practice

Organisation committee for:

PhD course: Language management, Lingphil (2019)

01/2017- 04/2017

Associate Professor, NHH (part-time) and Researcher (forsker II) SNF (part-time)

Course responsible of:

FSK10 (VOA045): East Asian culture and communication (elective, bachelor)

08/2011- 10/2016:

PhD Research Scholar in intercultural communication, FSK, NHH

Course responsible of:

FSK10 (VOA045): East Asian culture and communication (elective, bachelor)/ creation and

teaching

Organisation committee for:

PhD course: transferable skills: research communication and career planning, Lingphil (2016)

01/2011- 05/2011

Assistant Professor, University of Bergen, Norway and UiB

Course taught:

FRAN 201, translation course (Norwegian to French)

01/2007- 05/2011

Teacher of French and supervisor for new teachers, Folkeuniversitetet i Bergen

Evening classes for adults, all levels from beginners to conversation classes (up to 9 classes

per week)

01/2010- 10/2010

20

Assistant Professor, NHH

Course taught: FRA 010, French language and economy

08/2008- 07/2010

Teacher (lektor) at Bergen Kommune, Bergen

Taught French in secondary school and in primary school (morsmålslærer: for pupils with

French as their mother tongue)

Ytre Arna Skole (2009-2010) and Åstveit Skole (2008- 2009)

11/2006- 07/2008

Teacher (lektor) Danielsen Videregående skole, Bergen

Taught French and worked as a substitute teacher in French, English and marketing,

09/2005- 05/2006

Teacher, Lille Graduate School of management (ESC Lille), Lille, France

Taught French to foreign students: beginners and intermediate levels

07/2004- 11/2004

Teacher, Chanel Headquarters Shanghai, China and in a French school in Shanghai

Taught of French to company employees

01/2004- 05/2004

Assistant in French, NHH, Norway

Taught 4 hours a week as “kollokvieleder”

Guest lectures at university level

2021 Guest lecturer NHH executive MBA MØST