Disclaimer

This non-paper from the Commission services is for information and discussion purposes only. It

may not be interpreted as stating an official position of the European Commission.

EFFECTS ANALYSIS (EA) ON THE

EUROPEAN DEPOSIT INSURANCE SCHEME (EDIS)

Contents

1. CONTEXT OF THE EFFECTS ANALYSIS (EA) ................................................................ 6

2. THE EXISTING FRAMEWORK FOR DGS IN THE EUROPEAN UNION ....................... 7

3. EFFECTS ANALYSIS OF THE MAIN POLICY OPTIONS ................................................ 9

3.1. The design of a pan-European deposit insurance scheme ............................................. 9

3.2. Policy options for risk and governance pooling ......................................................... 10

Mandatory reinsurance ................................................................................ 12 3.2.1.

Mandatory lending ....................................................................................... 13 3.2.2.

Fully mutualised fund .................................................................................. 15 3.2.3.

3.3. The incentive structure: moral hazard and risk reduction ........................................... 16

3.4. Comparing the three policy options ............................................................................ 17

Assessing risk absorption via SYMBOL ..................................................... 18 3.4.1.

Assessing diversification of risks under the three alternative 3.4.2.

arrangements ................................................................................................ 27

Assessing the implications of interconnection among EU banks ................ 28 3.4.3.

Benchmarking policy options ...................................................................... 29 3.4.4.

4. THE TRANSITIONAL PERIOD: THE RATIONALE BEHIND THE 'THREE-STAGE

APPROACH' ......................................................................................................................... 33

The transition under the Commission proposal ........................................... 33 4.1.1.

Analysis of uncovered liquidity and uncovered losses in the transition 4.1.2.

period via SYMBOL.................................................................................... 34

Key results ................................................................................................... 34 4.1.3.

Funding path ................................................................................................ 35 4.1.4.

5. INTERACTION BETWEEN EDIS AND NATIONAL DISCRETIONS UNDER THE

DGSD .................................................................................................................................... 39

5.1. Irrevocable payment commitments (IPC) ................................................................... 39

Issue description .......................................................................................... 39 5.1.1.

Policy options and comparison .................................................................... 39 5.1.2.

Conclusion ................................................................................................... 42 5.1.3.

5.2. Temporary high balances (THB) ................................................................................ 42

Issue description .......................................................................................... 42 5.2.1.

Policy options and comparison .................................................................... 43 5.2.2.

2

Conclusion ................................................................................................... 44 5.2.3.

5.3. Scope of EDIS ............................................................................................................ 44

Non-CRR entities ......................................................................................... 45 5.3.1.

Third-country branches ................................................................................ 47 5.3.2.

5.4. EDIS cover in case of alternative and preventive measures ....................................... 51

Issue description .......................................................................................... 51 5.4.1.

Policy options and comparison .................................................................... 54 5.4.2.

Conclusion ................................................................................................... 55 5.4.3.

5.5. Contributions .............................................................................................................. 56

Issue description .......................................................................................... 56 5.5.1.

Policy options and comparison .................................................................... 56 5.5.2.

Conclusion ................................................................................................... 57 5.5.3.

6. ANNEXES............................................................................................................................. 59

6.1. Modelling expected losses for EDIS vs other risk pooling models ............................ 59

6.2. Brief description of the data sample and the simulation exercise in SYMBOL ......... 62

6.3. Brief description of SYMBOL.................................................................................... 63

6.4. Outputs on payout analysis via SYMBOL .................................................................. 68

6.5. Outputs on the effectiveness of a fully-mutualised EDIS relative to national-level

DGS, via SYMBOL .................................................................................................... 83

6.6. Outputs on payout analysis on the transitional period via SYMBOL ......................... 89

6.7. List of European banking groups in the CDS premia analysis ................................... 92

6.8. Outputs of the CDS spread analysis ............................................................................ 93

3

DISCLAIMER

This non-paper from the Commission services is for information and discussion purposes

only. It may not be interpreted as stating an official position of the European Commission.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

On 24 November 2015 the Commission adopted a proposal for a European Deposit Insurance Scheme

(EDIS). The Commission considered the 2010 impact assessment, leading to the adoption of the

current Deposit Guarantee Scheme Directive (DGSD), as a solid basis for the EDIS proposal with the

same 0.8% target level than the current DGSD. This effects analysis complements the impact

assessment for the DGSD.

This paper analyses the effects of three options for the set up of deposit insurance within the Banking

Union. In addition it analyses the effects of different options on a number of more specific issues in

the design of EDIS.

Effects of different options for deposit insurance in the Banking Union

Policy options. Three mandatory approaches have been considered: mandatory reinsurance,

mandatory lending and a mutualised fund. The mandatory reinsurance model is assessed as a steady-

state option on the basis of different levels of distribution of resources between national DGSs and the

European reinsurer, plus different caps for uncovered liquidity and losses for the European reinsurer.

The mandatory lending model requires participating DGSs to provide up to 0.5% of covered deposits

to cover the liquidity shortfall. As all loans must be repaid in full by the borrowing DGS, the lending

DGS does not incur any loss. The fully mutualised fund, which is the steady state under the EDIS

proposal, replaces national DGS in providing full liquidity and absorbing any loss. The co-insurance

model under the EDIS proposal was not specifically tested, as it is only a variation of the mandatory

re-insurance model (with participation from the first euro of loss) and because the EDIS proposal only

envisaged it as a transitory stage to a fully mutualised fund.

An EU solution. By analysing stressed scenarios for 99.8% of EU-bank assets, the non-paper shows

that, under all three options, pooling risk delivers in every circumstance a significantly stronger

deposit guarantee system than a system of purely national schemes with voluntary lending. The

expected shortfall of a single scheme is lower than that of multiple national schemes.

The three policy options are tested against three criteria:

1. Risk absorption;

2. Efficiency and cost neutrality; and

3. Limits on moral hazard.

Risk absorption. The mutualised fund (EDIS) performs better than the mandatory re-insurance and

lending schemes in all the simulations, both in providing liquidity and absorbing losses. In terms of

liquidity, the mutualised fund makes available more funds, as compared to the other options. In terms

of loss absorption, the probability of remaining losses after recovery in insolvency/resolution

proceedings, implying failure of the DGS itself, is the smallest under the fully mutualised fund, as

extraordinary contributions are used to cover losses, as opposed to mandatory lending where national

DGSs fully bear the losses, as they receive funds in the form of loans.

4

Mandatory reinsurance outperforms mandatory lending with respect to liquidity and losses, even

when its caps are low and it performs close to the mutualised fund without caps. The fully mutualised

fund (EDIS) also offers greater risk diversification (portfolio effects), which minimises the expected

losses for the whole financial system in case of an asymmetric shock. Indeed, EDIS requires a risk-

based contribution from each participating bank calculated relative all other banks in the Banking

Union rather than a risk-based contribution calculated only relative to other banks in the same

national banking system.

Moreover, there is strong interconnection between the probabilities of default of all banks within the

Banking Union, also across borders. As a consequence, a national DGS cannot be fully insulated from

developments in a DGS in another Member State, which is unable to withstand a shock in its local

banking system. In a system of single DGSs, this implicit risk would need to be made explicit by

obliging banks to pay for it within a two-tier system of risk-based contributions: a bank-level

contribution to account for idiosyncratic risks at national level and a contribution at the national

banking system level to account for interconnectedness. The mutualised fund solution overcomes this

need by raising funds at bank level relative to all other participating banks across the Banking Union,

so factoring in cross-border interconnectedness in one single contribution from each participating

bank. Due to its loss absorbing capacity, a fully mutualised fund (EDIS) would be in a good position

to deal with potential spill over effects among all banks in the Banking Union. A centralised

governance of the mutualised fund would also ensure the uniform implementation of the risk-based

contribution without the need for a two-tier system of national and supranational contribution rules.

Efficiency and cost neutrality. The mutualised fund and the mandatory reinsurance model with a

central body are similar in terms of efficiency and offer a better management of funds than mandatory

lending in the collection and during liquidation or resolution. While all options offer a neutral solution

in terms of the total cost of the intervention, the mutualised fund offers a more balanced redistribution

of losses across banks, which does not penalise banks for their nationality but only for the way they

manage their risk exposures.

Moral hazard. The mandatory lending model offers protection against moral hazard because full

repayment of loans is required, implying no participation in losses by the lending DGS. However, the

different safeguards foreseen for the reinsurance and the mutualised fund model (EDIS) are

comparable in terms of reducing moral hazard incentives. Bank level risk-based contributions in EDIS

reduce incentives for banks to misbehave. With the creation of the Single Supervisory Mechanism

and the Single Resolution Mechanism, the increased centralisation of prudential rule-making and

supervision has already significantly reduced monitoring costs and so moral hazard. These safeguards

come on top of other ‘built-in’ features of EDIS, such as the unified governance of funds or the

disqualification to the access to coverage in case a Member State violates the principle of sincere

cooperation.

The transitional period in the EDIS proposal. This non-paper also discusses the transition from

reinsurance, to coinsurance and to a steady-state fully mutualised fund under the EDIS proposal,

comparing the alternative phases and assessing the effects on the current funding path. The analysis

shows that the loss absorbing capacity of EDIS, compared to a purely national system, strongly

increases along the different phases. The analysis also deals with the evolution of the EDIS funds

suggesting a funding path where contributions to the fund are spread as evenly as possible over time

to avoid potential cliff effects.

5

Specific issues in the design of EDIS

National options and discretions. The DGSD leaves Member States with a degree of discretion in a

number of areas. EDIS would preserve such discretion to the extent it is necessary to accommodate

Member States' specificities. However, wide differences in national implementation due to retained

discretions could impair depositor confidence and the effectiveness of the internal market. The effect

analysis therefore reviews the interaction of the EDIS proposal with national discretions under the

DGSD, identifying those which should be retained and indicating how the retained discretions would

be managed under EDIS.

Irrevocable Payment Commitments (IPC). The use of irrevocable payment commitments (IPC) are

not envisaged in the EDIS proposal. The analysis identifies a number of operational and procedural

risks that support this decision.

Temporary High Balances and other options and discretions. The DGSD envisages that the DGSs

provide coverage also for temporary high balances (THBs) in an account, as a result of special

transactions, such as real estate transactions or insurance claims. The level of protection and time

period is left to the discretion of the Member States. The information provided by Member States,

together with the exceptional nature of these transactions, suggests that their magnitude is likely to be

small compared to the 'regular' deposit claims in case of a pay-out. Therefore, the policy option

adopted in the EDIS proposal to cover THBs appears to be correct.

EDIS scope. As regards non-CRR entities, the effects analysis looks at different options in terms of

scope concerning non-CRR entities and third country branches. On non CRR-entities, the EDIS

proposal would cover all credit institutions affiliated to a participating DGS. On third country

branches, the proposal respects the discretion granted by the DGSD to Member States as regards the

equivalence test of deposit protection for third country branches. Therefore coverage by EDIS

depends on the exercise of such discretion. As regards preventive or alternative measures, these

should not be covered by EDIS since they are only used by a very limited number of Member States

and are therefore not considered to be core functions to be financed by EDIS. Instead, EDIS funding

for preventive and alternative measures would mutualize expenditures for measures that would be

exclusively decided by each Member State with no input from the central body (SRB).

Contributions. The principle that bank contributions to DGS should be risk-based is already

established by the DGSD. This analysis sets out how this principle could be applied in the EDIS

context. Notably, in the reinsurance phase of EDIS, where risks remain largely at the level of the

(national) DGS, a bank’s risk profile relative to the its (national) DGS peer group could determine its

risk-base. When EDIS becomes a system with shared risks at Banking Union level, starting with co-

insurance, an individual bank’s risk-base could be determined relative to all banks in the Banking

Union.

6

1. CONTEXT OF THE EFFECTS ANALYSIS (EA)

On 24 November 2015, the Commission adopted a proposal for a European Deposit Insurance

Scheme (EDIS).

1

The proposal builds on the existing Directive on Deposit Guarantee Schemes

2014/49/EU (DGSD), which harmonizes key elements of the current framework for national deposit

guarantee schemes (DGS). The DGSD benefited from a comprehensive impact assessment by the

European Commission in 2010

2

. That impact assessment already demonstrated that introducing a pan-

European deposit guarantee scheme would have a number of advantages compared to the current

system; the option of a pan-European scheme was not pursued at that time, but now forms the basis of

the EDIS proposal. In addition, the EDIS proposal maintained the current national DGSD target level

(0.8% of covered deposits at national level). Therefore, the Commission considered the EDIS

proposal to be founded on solid grounds.

During negotiations with the Council on the EDIS proposal, the Commission was invited to

supplement the impact assessment for the DGSD with an analysis of the effects of the policy choices

included in the proposal.

3

In addition, the ECON rapporteur in her working document of 16 June 2016

invited the Commission to provide an assessment of the impact of the EDIS proposal. In order to

facilitate progress in the negotiations, the Commission committed to the Council and European

Parliament to prepare such an "effects analysis" by October 2016

4

. The effects analysis, which is

presented in the remaining sections of this non-paper, comprises the following elements:

an outline of the existing framework for national DGS in the European Union;

the effects of the proposed EDIS proposal compared to alternative policy options; and

the interaction between national options and discretions under the DGSD and EDIS.

1

http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52015PC0586&from=EN

2

http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52010SC0834&from=EN

3

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-%2F%2FEP%2F%2FNONSGML%2BCOMPARL%2BPE-

585.423%2B01%2BDOC%2BPDF%2BV0%2F%2FEN

4

Letter of Vice-President Dombrovskis and Commissioner Lord Hill to the ECON Chair, Roberto Guatieri, and to the

Minister of Finance of Slovakia and President of the ECOFIN Council, Peter Kazimir, dated 14 July 2016.

7

2. THE EXISTING FRAMEWORK FOR DGS IN THE EUROPEAN UNION

The current DGSD Directive is the starting point for the EDIS proposal, which integrates some of the

main features of the Directive. Some of those features present operational challenges for

implementing EDIS, but will ultimately produce efficiency gains.

The scope of the DGSD requires all credit institutions to join an officially-recognized DGS at national

level, with the possibility for institutional protection schemes (IPS) to be recognized as DGS.

Depositors at bank branches in another Member State are reimbursed by the DGS in the host Member

State, which acts as a “single point of contact” on behalf of the home DGS.

The level of depositor protection under the DGSD has been harmonized at €100.000 per depositor,

per bank. The repayment deadline must be gradually reduced from 20 working days at present, to 7

working days by 2024 at the latest. During this transitional period, depositors in need may ask for a

so-called social pay-out, i.e. a limited amount to cover their costs of living to be paid within 5

working days.

In terms of depositor information, the DGSD ensures that depositors are aware of the key aspects of

protection of their deposits by DGS. For example, when depositing money in a bank, depositors must

countersign a standardised information sheet containing all relevant information about the coverage of

the deposit by the relevant DGS. Banks are obliged to provide their account holders with basic

information about depositor protection on an annual basis.

Under the DGSD, the target funding level for ex-ante funds of DGS is 0.8% of their covered deposits.

This target level must be reached by 2024. Exceptionally, if the DGS has made cumulative

disbursements in excess of 0.8% of covered deposits, Member States may extend the deadline for a

maximum of 4 years. This target level is a minimum and Member States can set higher levels for their

DGS. On the other hand, the DGSD also allows Member States, after approval by the Commission, to

set a lower target level at a minimum of 0.5% of covered deposits if their banking sector is dominated

by large banks which are unlikely to be liquidated and to trigger the use of DGS funds, also in view of

upcoming MREL/TLAC requirements.

DGS funds should consist, in principle, of cash and low-risk assets. A maximum of 30% of funding

can consist of payment commitments. In case ex-ante funding is insufficient, the DGS must

immediately collect ex-post contributions from the banking sector. As a last resort, the DGS should

have access to alternative funding arrangements such as loans from public or private third parties.

There may also be a voluntary mechanism of mutual borrowing between DGS from different EU

Member States (to date no such voluntary lending scheme has been agreed). Bank contributions to

national DGS must be risk-based, i.e. they must reflect the individual risk profile of the bank

concerned. This means that banks with a higher risk profile must contribute more to a national DGS.

The European Banking Authority (EBA) has adopted Guidelines for the calculation of such risk-based

contributions

5

.

As regards the use of DGS funds, the DGSD provides two mandatory functions for every DGS:

A payout function; and

Participation in resolution.

5

EBA, Guidelines on methods for calculating contributions to deposit guarantee schemes, 22 September 2015.

8

The pay-out function

6

is defined by the DGSD as the primary function, if deposits become

unavailable and it is the relevant counterfactual when determining the limits of other uses of the DGS.

As regards participation of the DGS in resolution,

7

in accordance with Article 109 of the BRRD, the

BRRD provides that a DGS is liable for the amount of losses that covered depositors would have

suffered after applying 'bail-in' or other resolution tools if these liabilities had not been protected from

such losses. The DGS participates in resolution either in an 'open bank' bail-in scenario or by

financing the transfer of deposits to a bridge bank and liquidating the remaining estate.

The DGSD also includes an option for DGS to have two additional functions. Member States may

allow DGS to (a) use their financial means so as to prevent failure of an institution under certain

conditions; and (b) finance a deposit book transfer and eventually other assets and liabilities in order

to preserve the access of depositors to covered deposits, in the context of national insolvency

proceedings. The DGSD also leaves discretion for Member States in other areas, for instance to use

DGS to cover temporary high balances in depositor accounts and to accept irrevocable payment

commitments in funding DGS.

The EDIS proposal builds on and completes these key features of the current DGSD. EDIS's target

level is the same (0.8%), bank contributions are risk-based, both deposit pay-outs and resolution

interventions are covered by EDIS, and certain national discretions are permitted to reflect Member

States specificities. Payment commitments are, however, not included under EDIS, for reasons of

operational efficiency: in a pay-out event funds must be quickly accessible and disbursable in order to

meet applicable deadlines.

6

Article 11(1) DGSD

7

Article 11(2) DGSD

9

3. EFFECTS ANALYSIS OF THE MAIN POLICY OPTIONS

This chapter discusses the policy options on which the EDIS proposal is based, as well as relevant

alternatives. Using an empirical analysis of the effects of the proposal, the effects of the EDIS

proposal are benchmarked against two main alternative models for a pan-EU approach to DGS in the

way options score against key objectives.

3.1. The design of a pan-European deposit insurance scheme

A single deposit insurance scheme is widely considered to be one of the three pillars of the banking

union, together with the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) and the Single Resolution Mechanism

(SRM). The rationale behind the single deposit scheme is to ensure resilience and further weaken the

sovereign-bank nexus. With a purely national DGS, depositor protection can be overwhelmed by

large local shock. As explained in chapter 2, the objective of the DGSD was to upgrade the capacity

of national DGS to withstand local shocks. The following sections assess whether the measures

provided in the DGSD are sufficient and whether a single deposit insurance scheme would enhance

depositor protection via scale and diversification benefits.

Designing a single deposit guarantee scheme for the banking union area involves the pooling of risk

and governance. Risk pooling implies the possibility of national DGS sharing losses at a

supranational level. Governance pooling implies a degree of mandatory coordination between national

DGS at a supranational level in delivering protection to depositors. Figure 1 below shows the list of

theoretically available options combining risk pooling and governance pooling. All the possible

combinations of risk and governance pooling assume a mandatory contribution by national DGSs or

by banks directly. A mechanism of voluntary lending is already in place with the DGSD, but it has

never been used so far. A voluntary mechanism of reinsurance might as well be unable to offer

(voluntary) protection mechanisms for shocks whose downside risk is a bank run.

Figure 1. Risk vs Governance pooling (all options)

Mandatory reinsurance by

independent national DGSs

Mandatory lending by

independent national DGSs

Full mutualisation among

independent national DGSs

Mandatory reinsurance by a

network of national DGSs

Mandatory lending by a

network of national DGSs

Full mutualisation by a

network of national DGSs

Mandatory reinsurance by a

single entity

Mandatory lending by a

single entity

Fully mutualised fund

In theory, there are at least nine combinations of risk pooling and governance pooling.

Risk pooling among national DGS can be envisaged along a spectrum ranging from mandatory

reinsurance and lending arrangements to full mutualisation. A mandatory reinsurance arrangement

among national DGS partially pools risk, but the pooling is contingent on the scale of funding

Risk pooling

Governance

pooling

10

required by the borrowing DGS and the probability of repayment to the lending DGS. A mandatory

lending arrangement also partially pools risk, but requires some minimum level of lending by

participating DGSs, irrespective of the scale of funding required and the probability of repayment. A

fully mutualised arrangement pools risk fully, implying that any losses incurred by a participating

national DGS will be directly covered by the common fund, which will raise funds directly from

banks.

Governance pooling among national DGS can be envisaged along a spectrum ranging from separate

bilateral arrangements, to arrangements centrally co-ordinated within a network, to unified

governance via a single entity. The degree of coordination required among national DGSs gradually

increases along this spectrum. A network of DGSs requires a minimum level of coordination through

a central body that would coordinate and require action in well-defined areas. National DGSs would

still retain control over areas that are not covered by the supranational agreement. Finally, governance

via a single entity would shift decision-making powers to a central institution that ensures the smooth

functioning of the scheme, using national DGSs as contact points. This option minimises coordination

costs in a crisis, when the risk of a bank run is highest. Nevertheless, centralising governance

increases the monitoring costs of all agents (national banks and supervisors), which may require

specific actions (as discussed in section 3.3)

3.2. Policy options for risk and governance pooling

A voluntary lending mechanism among Member States represents the status quo under the DGSD, but

it has never been used so far. Of the nine potential combinations of risk pooling and governance

pooling in Figure 1, three alternative steady-state arrangements are further assessed in this analysis

(see Figure 2):

A mandatory reinsurance via funding by a network of national DGSs (as in phase 1 of EDIS;

Option 1);

Mandatory lending among Member States via a network of DGS, as proposed by the

Commission in the context of DGSD (Option 2).

Full mutualisation among Member States via a single entity, which is the steady-state

arrangement underlying the EDIS proposal (Option 3).

Arrangements based on mandatory reinsurance, mandatory lending or a fully mutualised fund agreed

bilaterally among DGSs are not considered further in this analysis because, without some degree of

governance coordination through a supranational agreement, none of these arrangements would be

feasible in a Banking Union context. For example, the governance of these arrangements when and

under what circumstances the mandatory lending takes place and a coordination and enforcement

mechanism is necessary and would be very difficult if this would be left to national DGSs. Ultimately,

the incentive misalignment created in pooling risk without pooling governance would result in

coordination challenges, which would ultimately undermine depositor confidence in the capacity of

these arrangements to function effectively in a banking crisis.

11

Figure 2. Risk vs governance pooling (policy options)

Mandatory reinsurance by

independent national DGSs

Mandatory lending by

independent national DGSs

Full mutualisation among

independent national DGSs

Mandatory reinsurance by a

network of national DGSs

(Option 1)

Mandatory lending by a

network of national DGSs

(Option 2)

Full mutualisation by a

network of national DGSs

Mandatory reinsurance by a

single entity

Mandatory lending by a

single entity

Fully mutualised fund

(Option 3)

All three models will be compared in the steady state, i.e. as they could exist in the final phase of the

EDIS proposal. Note that the EDIS proposal only envisages a fully mutualised fund as a steady state

objective. However, for the purposes of this effects analysis, other options have also been considered

as steady state outcomes in order to compare and benchmark the outcomes of the available policy

options. The co-insurance model, which is one of the phases of the transitional period, is not included,

as it was originally designed only for the transition phases and its economic effects are in great deal

similar to a mandatory reinsurance model, which is already part of this.

It should be noted that none of the three arrangements envisages a common fiscal backstop, which

would be available if EDIS funding (including ex-post contributions by banks) proved insufficient in

a crisis. In the absence of a common backstop, the ultimate responsibility for deposit insurance

beyond the EDIS funding capacity would lie with the Member State concerned. The pros and cons of

providing a common fiscal backstop in terms of enhancing depositor confidence and reinforcing

financial stability are not examined in this analysis.

Box 1. Liquidity and loss: definitions

A DGS typically plays two interconnected roles in the context of a bank failure. First, the DGS must

immediately pay out for covered deposits. The DGS meets its pay-out commitments with available

funds and ex-post contributions in the few days following the crisis. In this role, the DGS is a liquidity

provider. Second, the DGS participates as a creditor in the subsequent resolution/insolvency

proceedings relating to the failed bank so as to recoup the funding used to cover the pay-out. To the

extent that these funds are not fully recovered, the DGS will be required to absorb a loss. The

following definitions of liquidity and loss are used throughout the following sections.

Liquidity shortfall (LS) is the amount of covered deposits in the failing bank which exceeds the total

available financial means in the DGS (i.e. under the DGSD, available funding plus extraordinary

contributions that the DGS can raise within 3 days from the pay-out event).

Uncovered liquidity shortfall (ULS): the amount of covered deposits in the failing bank that cannot

be covered either by the DGS through its own available financial means or through additional funding

Risk pooling

Governance

pooling

12

made available via a supranational arrangement.

8

Loss retention (LR) is the loss that still needs to be covered after collecting insolvency proceeds and

receiving long-term extraordinary contributions from the banks, but before additional the additional

funding made available by supranational agreements.

Uncovered loss (UL) is the loss that the national DGS or the Member State has to bear after

collecting insolvency proceeds, long-term extraordinary contributions from banks at national level

and after receiving additional funding made available via a supranational arrangement (in the case of

mandatory re-insurance or a fully mutualised fund) or after supranational funds have been (partially)

repaid under a lending arrangement.

Pay-out: the amount of covered deposits that a DGS is required to cover as a consequence of bank

failures.

Available Financial Means (AFM): amount of funds at the disposal of a DGS.

Extraordinary Contributions (EC): extraordinary contributions that can be raised by the DGS in

need within 1 year.

Recovery rate (R): the amount that can be recovered during insolvency proceedings.

Mandatory reinsurance 3.2.1.

The arrangement is a form of risk pooling based on a partial re-insurance of the risk that is evaluated

at a market price or with a market-like estimation (risk-based contribution) of potential funding

provisions to a DGS in need. The model reinsures with its own funds only after a national DGS has

depleted its own resources, which are capped at either 0.6% (option 1) or 0.4% (option 2) of national

covered deposits, plus an additional 0.5% that can be raised from banks through ex post extraordinary

contributions. The pooled funds would be managed by a central body, as it ensures uniform and rapid

procedures and governance in the event of a shock.

9

Compared to other models, the 'reinsurance effect' is defined by restrictions on the use of pooled

funds to absorb:

the liquidity shortfall; and

the loss retention (see Box 1).

The restriction can take the form of an obligation to deploy funds of the national DGS first and/or the

use of additional caps to the use of pooled funds for uncovered liquidity and/or losses (as in the

reinsurance model proposed by the Commission for the transition period). In addition, the

contribution to the reinsurance body is calculated on the basis of risk of the domestic banking system

that contributes via the national DGS.

8

The concept of "uncovered liquidity" does not mean that the national DGS would become free of its obligations to

reimburse depositors according to Art. 8(1) DGSD, instead the DGS would have to obtain alternative funding as

required by Art. 10(9) DGSD.

9

This model could also rely on a system of independent DGS that would allocate their contributions on their own books and

make them available upon request. This alternative option (Option 1A), would not be guaranteed to work successfully

in practice and would be difficult to manage in a crisis situation, when a liquidity provision is required immediately.

13

Table 1. Mandatory reinsurance model - Key characteristics

Governance

Risk-based

contribution

Total Cap

10

Ex post

contribution

Liquidity

shortfall

Excess loss

Supranational

agreement

National

banking

system level

Option 1: 0.2% covered

deposits at EU level and

0.6% at national DGSs

(plus 0.5% ex post)

Option 2: 0.4% covered

deposits at EU level, and

0.4% at national DGSs

(plus 0.5% ex post)

Collected only

by national

DGS

Cover set

between

20% and

80%

Cover set

between 20%

and 80%

In practice, Figure 3shows that the 'reinsurance effect' is spread across the liquidity and the loss

phases. Reinsurance intervention only comes after the national DGS has absorbed liquidity shortfall

and losses, until its own funds have been depleted. Caps on the liquidity shortfall and loss cover are

designed to prevent the depletion of the EU fund.

Figure 3. Reinsurance model - Disbursement Phases

Mandatory lending 3.2.2.

Mandatory lending via a network of DGS is a form of risk pooling that requires a minimum level of

funding provision by participating DGS, irrespective of the shock suffered by the national DGS and

the probability that the loan will be repaid. Funds are disbursed in the form of loan with a given

10

The "total cap" in the table describes the funds available in the reinsurance fund and in the national DGSs. In other words,

it allocates the amount of 0.8% of covered deposits which have to be collected under Art. 10 DGSD to the national and

the European level. Additional caps could be introduced to limited the amount provided by the re-insurance to prevent

first mover advantages and. The EDIS proposal contained in the re-insurance phase the caps that the EDIS intervention

cannot in any case be higher than 10 times the level of covered deposits of the national DGS in need and 20% of the

initial target level of the DIF.

14

maturity. For the purpose of the analysis, it is assumed that the funds pooled via mandatory lending

can go up to 0.5% of total covered deposits.

11

These funds support the resources of national DGSs,

which are 0.8% of covered deposits (as already required by the DGSD).

The governance of the funds remains at national level, with procedures for the collection and use of

disbursed funds to be implemented by national DGSs. The maximum amount to be disbursed by each

national DGS will be quantified on the basis of total covered deposits of the lending DGSs, but raised

from banks on the basis of a risk-based contribution calculated on the risk of local banks.

Table 2. Mandatory lending - Key characteristics

Governance

Risk-based

contribution

Total cap

Ex post

contribution

Liquidity

shortfall

Excess

loss

Supranational

agreement

National

banking

system level

0.8% at national

DGSs and 0.5% of

covered deposits

through loans by

other participating

national DGSs

Collected only

by national

DGS

Cover by other

national DGS of

up to 0.5% of

covered deposits

No

coverage

This mandatory lending arrangement is also designed to produce significant disciplinary effects, as it

issues funds in the legal form of a loan, although funds must be made available by national DGS

without a pre-funding obligation. This arrangement does not cover any uncovered losses of the

national DGS, as any loans to other DGS must be fully repaid. Uncovered losses must be addressed

by the national DGS (e.g. via extraordinary ex-post contributions from banks or alternative funding

arrangements).

Figure 4. Mandatory lending model - Disbursement Phases

11

This was the distribution proposed in the DGSD Commission proposal in 2010 and is also currently in the voluntary

lending regime of Art. 12 DGSD.

15

As a result, the mandatory lending arrangement produces its main effects in the initial pay-out phase,

as additional resources are made available exclusively to cover an uncovered liquidity shortfall. As

the obligation to repay the loans from other DGS takes effect, there is no loss absorption from the

arrangement and the risk sharing benefits disappear over time (see Figure 4).

Fully mutualised fund 3.2.3.

Mutualisation via a single entity is a form of risk pooling, which requires the single entity to assume

risk that is equally distributed among participating banks. This is the arrangement underlying the

steady-state phase of the EDIS proposal. In the EDIS proposal, the total funds collected (DIF) and

made available by the single-entity (the Single Resolution Board, SRB) would be equal to 0.8% of

total covered deposits, pre-funded, and 0.5% through ex post extraordinary contributions. The overall

cap does not change compared to the other alternatives. The harmonised governance of the procedures

for the collection and the use of the funds in liquidation and resolution is the distinguishing aspect of

this arrangement. In particular, the SRB would apply one single risk-based contribution formula

across the banking union area. This redistributes risk across the participating banks based on their

individual risk profile and not on the risk profile of their national banking system. As discussed

below, the risk diversification effect is most effective when risk is effectively distributed across all

banks according to their risk rather than their geographical location and is fully in line with the basic

concepts of a Banking Union.

Table 3. Fully mutualised fund - Key characteristics

Governance

Risk-based

contribution

Total cap

Ex post

contribution

Liquidity

shortfall

Excess loss

EU institution

Bank level

0.8% of covered

deposits pre-

funded, plus 0.5%

ex post

contributions

Yes

Fully covered

with available

liquidity

Fully covered

with available

funds

The fully mutualised fund is designed to provide financial stability through incrementally increasing

the risk absorption, i.e. the immediate availability of funds for an uncovered liquidity shortfall and

uncovered losses. Harmonised risk-based contributions and unified governance of the funds would

also provide disciplinary effects against the moral hazard risk (see section 3.4.4).

16

Figure 5. Fully mutualised Fund model - Disbursement Phases

3.3. The incentive structure: moral hazard and risk reduction

Moral hazard in the context of deposit insurance typically concerns the risk of opportunistic behaviour

among banks and depositors in exploiting the implicit state protection of deposits. Among banks, such

opportunistic behaviour can take the form of riskier activities, so as to boost profits, leaving

governments (taxpayers) at greater risk of having to step in to protect depositors in the event a bank

fails. Moral hazard also affects depositors, who can 'free-ride' on the state guarantee to deposit money

where they receive a higher interest rate, regardless of a bank's riskiness. The risk of such

opportunistic behaviour is associated with deposit insurance protection whether it is a national or a

supranational one.

12

To address this form of moral hazard, governments typically enact prudential

regulation to strengthen bank capital, use banking supervision to monitor risk-taking behaviours and

design resolution mechanisms to provide incentives to banks’ management and shareholders to avoid

excessive risk.

12

For an overview of the literature on moral hazard (of banks and depositors) and deposit insurance schemes, among others,

please see B. Bernet & S. Walter (2009), "Design, structure and implementation of a modern deposit insurance

scheme", SUERF – The European Money and Finance Forum, Vienna. Karas, A., Pyle, W. and Schoors, K. (2013),

Deposit Insurance, Banking Crises, and Market Discipline: Evidence from a Natural Experiment on Deposit Flows and

Rates. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 45: 179–200; C. Calomiris & M. Jaremski (2016), "Deposit Insurance:

Theories and Facts", NBER Working Paper, N. 22223, April. There is also a growing stream of academic literature that

associates the deposit insurance schemes with damaging moral hazard behaviours in the long-run (A. Demirgüç-Kunt &

E. J. Kane (2002), "Deposit Insurance around the Globe: Where Does It Work?", The Journal of Economic

Perspectives, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 175-195; A. Demirgüç-Kunt & E. Detragiache (2002), "Does deposit insurance

increase banking system stability? An empirical investigation", Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 49, pp. 1373-

1406; D., Anginer, A. Demirguc-Kunt, M. Zhu (2014), "How does deposit insurance affect bank risk? Evidence from

the recent crisis", Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 48, pp. 312-321). Moreover, in reassessing Diamond &

Dybvig’s (1983) model, some authors pointed out that demandable debt may not be the optimal contract for banks (see,

for this discussion, Calomiris & Jaremski, 2016). Nonetheless, as long as banks rely on demandable debt and depositors

ask for deposit-taking services, a deposit insurance scheme typically provide sufficient risk absorption to avoid bank

runs in a crisis.

17

Supranational arrangements for deposit insurance can create an additional source of moral hazard if

not accompanied by appropriate safeguards. The ‘safety net’ provided by these supranational

arrangements, beyond national DGS cover, could encourage local banks to assume more risk and

encourage local supervisors to be more lenient. In pursuing national policy objectives, Member States

could potentially adopt national legislation that creates incentives for increased risks on the balance

sheets of financial institutions as the potential costs of a bank failure would be borne by all Member

States. The possibility of this source of moral hazard is acknowledged in the EDIS proposal, which

builds on and reinforces safeguards that already exist under the DGSD. These safeguards are:

A uniform coverage level of deposit protection, capped at €100.000 across the European

Union, provides the same incentives for all EU depositors to exercise a minimum level of

control over banks’ behaviours;

Accessibility to the coverage by the DIF can be prevented if a national DGS "fails to comply"

with key provisions of the DGSD or if the relevant administrative authority, or any other

relevant authority of the respective Member State have acted in a way that runs counter to the

principle of sincere cooperation as laid down in Article 4(3) of the Treaty on European Union;

Prudential regulation, which sets capital requirements and other requirements to limit banks’

risk-taking, are drafted and implemented at EU level;

In initial (reinsurance) phase, national DGS funding must be fully exhausted before accessing

pooled funding which is capped; this provides powerful incentives for national authorities to

monitor the risk of domestic banks and so limit the risk of having to use deposit insurance.

Together with prudential rules, supervisory practices are also increasingly converging at

European level, and in particular for the banking union area, the introduction of the Single

Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) has taken over prudential supervision of national supervisors

(directly for significant banks and indirectly for less significant ones);

A resolution mechanism, led by the Single Resolution Board, has been established to provide

a single framework for resolving banks, coordinating the work of national resolution

authorities; such a mechanism ensures that all banks within the Banking Union are subject to

the same resolution system, which will provide similar incentives for banks across Member

States;

The BRRD has introduced a preference for DGS claims in the insolvency proceedings and

also an MREL requirement to protect this senior class of creditors.

EDIS envisages that the SRB should be responsible for use of the DIF, so as to define clear

procedures for national DGSs and domestic banks to access the EDIS funds in every

circumstance;

Last, but not least, the bank contributions to the DIF will be risk-based and defined in detail

by level-2 rules. (Risk-based contributions will be part of a separate effects analysis).

Moreover, it seems highly improbable that a Member State would deliberately decide to damage its

own banking sector so as to avail of access to EDIS.

3.4. Comparing the three policy options

The impact of steady-state risk pooling as proposed in EDIS, compared to the status quo of 'no-

pooling', has already been evaluated in an earlier paper for the AHWG and the empirical analysis is

re-presented in Annex 6.5. In particular, the analysis suggests that the proposed steady-state EDIS

18

consistently outperforms the current system of harmonised coverage levels

13

based on voluntary

lending among national DGSs. The pan-European solution has a higher absorption capacity and is

better equipped to withstand multiple pay-out events.

Instead, the analysis that follows compares the effects of the three main models identified in previous

sections in the steady state.

Assessing risk absorption via SYMBOL 3.4.1.

This section tests the theoretical framework, developed in the previous section, using the

unconsolidated balance sheet data of individual European banks to calculate the probabilities of

default through the so-called 'SYMBOL' model (see Annex 6.3 for more details).

14

For each bank in

each simulation run, SYMBOL determines whether it fails. A bank failure happens when simulated

gross losses exceed the total actual capital. These cases trigger the DGS intervention to reimburse the

amount of covered deposits of the failed banks.

15

These basic blocks of the analysis are repeated

100.000 times and results are then aggregated at the EU level. The same set of underlying simulated

banks’ failures is used to assess the performance of the three insurance schemes.

By simulating a shock on probabilities of default of banks, the model calculates aggregate shortfalls,

i.e. losses not covered by national DGSs and by the different European solutions, and compares them

between the three models to establish which one minimises the shortfall for the national and EU

DGSs. In other words, it estimates the absorption capacity of the three models discussed above, when

the area suffers an asymmetric shock.

The performance of the three systems is assessed against two risk absorption dimensions:

a. the ability to cover deposits in the immediate aftermath of a banking crisis (at the payout);

and

b. the ability to cover losses in the long-run, i.e. after the liquidation proceeds have been

collected.

First, the ability to cover deposits in the immediate aftermath of a banking crisis is measured by the

amount of insured deposits that are not covered, given that the funds immediately available are

insufficient. The available funds comprise the national DGS pre-funded amount, together with the

liquidity made available: i) by the reinsurance scheme or the central body, or ii) by other DGSs in the

form of mandatory loans.

Second, the losses that are ultimately borne by the national DGS and the central body in the medium-

long term are computed as the difference between the initial pay-out and the funds only available at a

later stage, including: i) extraordinary ex-post contributions from banks; ii) amounts recovered from

banks’ insolvency procedures, and iii) in the case of the re-insurance scheme, the share of uncovered

losses taken up by a central body. In this analysis, extraordinary ex-post contributions (EC) are equal

13

The 2010 impact assessment (p. 32-33, plus annexes 4-6) concludes that the level of coverage should be harmonised and

suggests a specific level for that. http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/bank/docs/guarantee/20100712_ia_en.pdf

14

Note that Cariboni et al. (2015a) run simulations country by country independently. Instead, we first simulate losses

jointly for all EU 28 banks, then distribute them across countries. This simulation approach is the same applied in

Cariboni et al (2015b). Please, see Cariboni J., Di Girolamo F., Maccaferri S., Petracco Giudici M. (2015a): Assessing

the potential reduction of DGS funds according to Article 10(6) of Directive 2014/49/EU: a simulation approach based

on the Commission SYMBOL model, JRC Technical report JRC95181 (forthcoming); and Cariboni J., Petracco Giudici

M., Maccaferri S., Hallak I., Pfeiffer P. (2015b): Sustainability Assessment of the European Deposit Insurance Scheme,

JRC Science for Policy Report, JRC98207

15

It would be possible to run the analysis by assuming that the larger banks would be resolved while only the smaller banks

would go into insolvency.

19

to 0.5% of the amount of covered deposits of the relevant Member State. In addition, in this model EC

cannot be raised in the short term (few days after the crisis) to repay depositors, but are available in

the long term to cover the DGS losses.

As regards the computation of the amounts recovered from banks’ insolvency procedures, the

recovery rate has been alternatively set equal to i) 90% of the amount of covered deposits of the

failing banks (a 30 percentage points increase over the average recovery rate in the EU), and ii)

country-specific recovery rates, increased by 30%.

16

The increase over the regular rate of recovery is

added to reflect that DGS claims will receive priority in a resolution/insolvency procedure under the

BRRD.

3.4.1.1. Mandatory reinsurance

In a mandatory reinsurance system, national DGSs operate alongside an ex-ante funded central body

(CB). National DGSs are required to reimburse pay-outs and only if there are still uncovered deposits

and national funds are fully depleted, the CB intervenes. Five key assumptions underpin the model.

1. Member States have achieved on aggregate the target (0.8% of covered deposits), which is

partly allocated to the CB and partly to national DGSs. Beta is the share of funds that remains

available to the national DGS. The analysis assesses three scenarios: i) beta = 75%, (i.e. 0.2%

of covered deposits sit with the CB while 0.6% of covered deposits are available in national

DGSs). ii) beta = 50% (0.4% of covered deposits sit with the CB with an equal amount being

available at national DGSs) and iii) beta = 25% (0.6% of covered deposits sit with the CB

with 0.2% of covered deposits being available at national DGSs).

2. When necessary, the central body intervenes to provide reinsurance liquidity to cover a share

(alpha) of liquidity shortfalls. This is a first cap. Alpha may vary over a wide range of values,

up to 100%.

3. The total amount that the CB can contribute to is also capped, according to the following

formula:

This cap is equal to the smallest of following:

On the one hand, it considers the funds available at the national DGS (equal to a share

beta of the total target, see above), and multiplied it by a factor z>1.

On the other hand, it considers the share of the target available at the aggregate EU-level,

multiplied by a factor y<1.

This cap applies to both the liquidity provided in the short term and the amount of losses

borne by the CB in the long term.

4. The DGS can call on banks to supply extraordinary contributions (0.5% of covered deposits)

to cover its losses.

In order to compare options, the mandatory reinsurance model is assessed with different caps.

Table 4. Parameters used for the analysis of mandatory reinsurance

16

Country-specific recovery rates used in this analysis are available in the World Bank's Doing Business 2016 Report.

20

z

y

75%

20%

10

20%

75%

20%

10

80%

75%

80%

10

20%

75%

80%

10

80%

75%

60%

10

60%

75%

100%

10

100%

50%

20%

10

20%

50%

20%

10

80%

50%

80%

10

20%

50%

80%

10

80%

50%

60%

10

60%

50%

100%

10

100%

25%

20%

10

20%

25%

20%

10

80%

25%

80%

10

20%

25%

80%

10

80%

25%

60%

10

60%

25%

100%

10

100%

Note: is the share of funds that remains available to the national DGS; is the share of liquidity

shortfall that can be covered by the central body; z and y are two parameters in the formula defining

the maximum amount (cap) of the central body's funds that can be used by a single DGS: z is a

multiple of a single DGS resources, y is a share of the resources of the central body.

3.4.1.2. Mandatory lending

Under the mandatory lending approach, whenever a national DGS experiences a liquidity shortfall,

the other DGSs are mandated to lend money to the DGS whose available financial means have been

depleted. The lending regime is subject to specific conditions:

1. The AFM of each DGS reach the full target, as defined in the DGSD (i.e. 0.8% of the total

amount of covered deposits in the relevant MS);

2. The total amount that can be borrowed is capped to 0.5% of the covered deposits of the

borrowing DGS;

3. The loan is apportioned among creditor DGSs in proportion to their size;

4. Loans are assumed to be recovered at 100% and for this purpose the borrowing DGS raises

the maximum amount of ex-post contributions (0.5% of covered deposits); if the loan

received is lower than the ex post contributions residual resources are used to cover the losses

of the DGS.

3.4.1.3. Fully mutualised fund

Under this scenario, a single deposit insurance fund at EU-28 level is established. The available

financial means are equal to 0.8% of covered deposits in the EU. As there is no external actor

providing extra resources, there is no distinction between liquidity shortfall and liquidity retention.

The fully mutualised fund can call extraordinary contributions from participating banks (0.5% of

covered deposits) to cover its losses.

3.4.1.4. Simulation of pay-outs

The effect analysis has been developed at the individual bank level and results are then aggregated at

the EU-level. Bank failures implying a DGS intervention are simulated by the SYMBOL model (see

Annex 6.3 for a description). The crisis scenarios have also been generated by the SYMBOL model,

which is based on individual bank balance sheet data. In each simulation, each bank either fails or

21

survives, depending on its initial level of capital and the severity of the crisis. The national DGS is

called upon to cover the insured deposits of failed banks. These central premises of the effect analysis

are repeated 100.000 times.

The three risk pooling arrangements have been assessed in relation to the level of implied uncovered

liquidity shortfall and loss. In particular:

a) Uncovered liquidity shortfall measures the inability of a given scheme to cover deposits in the

immediate aftermath of a banking crisis. This concept corresponds to the amount of insured

deposits that are in fact not covered in the event of a banking crisis, given that funds are

insufficient. The available funds comprise the national DGS pre-funded amount, together with

the liquidity made available: i) by the central body in the reinsurance scheme, or ii) by other

DGSs in the form of mandatory loans.

b) Losses in the medium-long term, which are ultimately borne by the national DGS and by the

central body (in the case of re-insurance), are computed as the difference between the initial

payout and the funds only available at a later stage, i.e. i) banks’ extraordinary contributions

to the DGS and ii) amounts recovered from banks’ insolvency procedures.

The data used for the present exercise is as of 2013

17

. The dataset covers a sample of around 3,400

banks from the EU-28, representing 99.86% of EU28 banks’ total assets (see Table 5).

18

The analysis

focuses on total assets, risk-weighted assets and total capital and/or capital ratios, as well as customer

deposits.

Table 5. Sample banks dataset (data from 2013)

Number of

banks

Total assets

bn€

RWA bn€

Covered

deposits bn€

Capital bn€

3,359

38,144

14,635

6,474

1,939

3.4.1.5. Key Results

This section compares the three options as follows:

a) Fully mutualised fund against mandatory lending

b) Fully mutualised fund against mandatory reinsurance

c) Mandatory reinsurance against mandatory lending

In each case, both the short term (uncovered liquidity shortfall) and the medium-long term

performance (uncovered loss) are evaluated. The reported charts and figures refer to rather extreme

crisis scenarios, involving simulations where at least one of the two compared schemes yields

uncovered liquidity shortfall or loss. In less extreme scenarios (some 90% of the simulations), the

alternative schemes are obviously equivalent.

All charts presented in this section focus on the worst 1% of simulations (i.e. percentiles from 99

th

to

100

th

on the x-axis), corresponding to banking crises of increasing severity. In all charts, the severity

of the crisis increases moving from the left to the right.

17

Data provided by Bankscope, a proprietary database of banks’ financial statements produced by Bureau van Dijk.

18

We use the amount of total assets in the banking sector excluding branches as provided by ECB as reference for the

population.

22

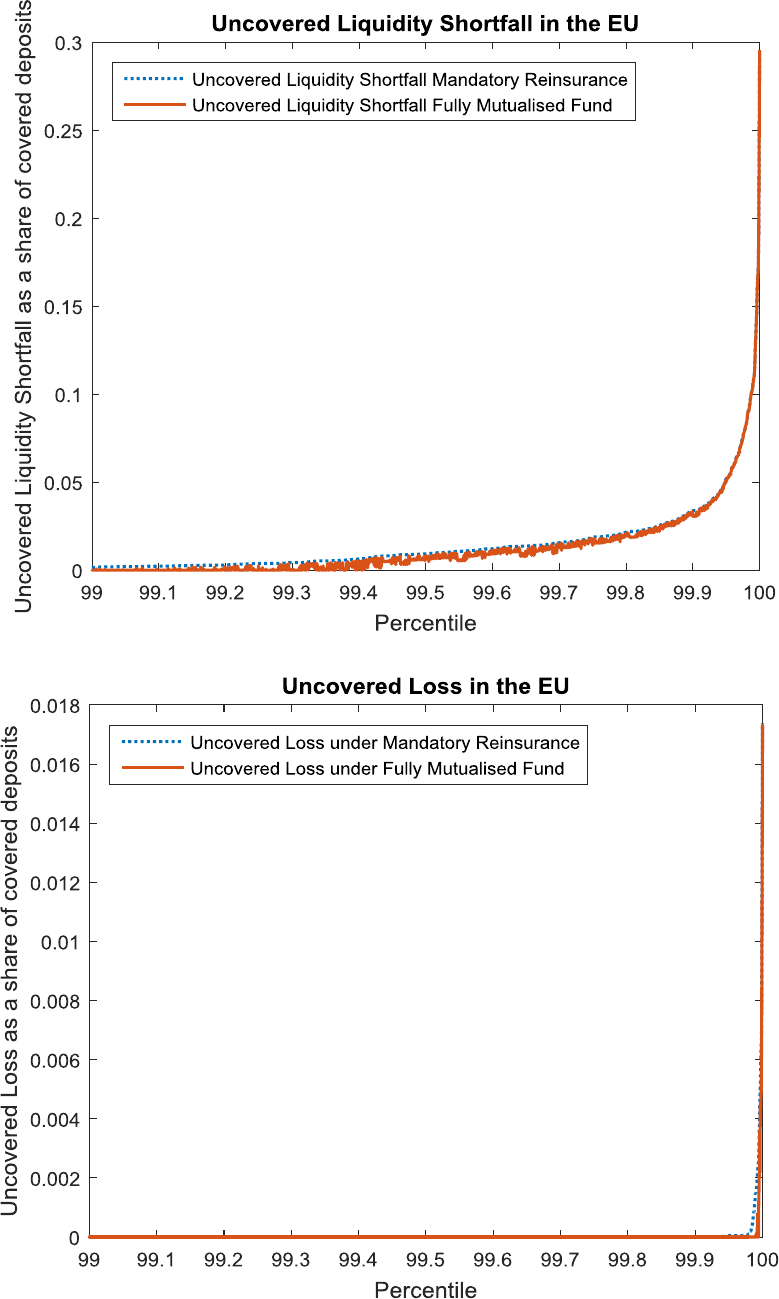

The fully mutualised fund against mandatory lending

Figure 6 shows the distribution of uncovered liquidity associated with each SYMBOL simulation.

Points on the far right of the curve represent more severe crisis scenarios, and are indeed associated

with larger amounts of uncovered liquidity shortfall. The curve representing uncovered liquidity

shortfall under mandatory lending (dotted) is always above the curve representing uncovered liquidity

shortfall under the mutualised fund (solid). The conclusion is that in none of the simulations

mandatory lending is able to deliver a smaller amount of uncovered liquidity shortfall than a

fully mutualised fund. This is because loans are capped at 0.5% of the covered deposits of the

borrowing DGS under mandatory lending, while under fully mutualised fund a larger amount of

liquidity is available.

Figure 7 shows the distribution of medium-long term losses associated with each SYMBOL

simulation. Again, points on the far right of the curve represent more severe crisis scenarios, and are

indeed associated with larger losses. The conclusion is that full mutualisation again turns out to be

superior to mandatory lending in terms of uncovered losses for national DGS. Indeed, the curve

representing uncovered losses under mandatory lending (dotted) is always above the curve

representing uncovered losses under full mutualisation (solid). In other words, uncovered losses under

full mutualisation are always smaller than under mandatory lending. This is due to the fact that under

mandatory lending, extraordinary contributions raised by the DGS and amounts recovered from

insolvency procedures are devoted to repay the loans instead of being used to cover the DGS losses.

Figure 6. Aggregate uncovered liquidity shortfall under mandatory lending (dotted line) and

fully mutualised fund (solid line), EU28.

23

Figure 7: Aggregate uncovered losses under mandatory lending (dotted line) and under fully

mutualised fund (solid line), EU28

The fully mutualised fund against mandatory reinsurance

The fully mutualised fund offers greater absorption capacity than mandatory re-insurance for

short term uncovered liquidity needs in all the simulations. This is because more funds are

available to the national DGS under a fully mutualised fund than under mandatory re-insurance,

where various caps are foreseen. For instance, with an example of parameters' combination,

19

Figure 8

shows how the curve associated with the fully mutualised fund (solid) is always below the curve

associated with the mandatory re-insurance scheme (dotted). Results shown in Figure 8 hold for other

combinations of parameters (see Annex 6.4). It should be noted, however, that when a central body is

allowed to cover liquidity shortfalls and losses in full (i.e. alpha and y=100%), the performance of the

mandatory reinsurance scheme is only slightly inferior to that of a fully mutualised system.

A fully mutualised fund offers greater absorption capacity than mandatory re-insurance also

for medium-long term uncovered losses. As the amount of losses borne by the central body is

capped under mandatory reinsurance, the central body can bear losses until its funds are depleted

under the fully mutualised fund. As suggested in Figure 9, the amount of uncovered losses is larger

under reinsurance than under full mutualisation in every SYMBOL simulation.

19

beta equals 75%, and alpha and y are both set at 60%

24

Figure 8. Aggregate uncovered liquidity under mandatory reinsurance (dotted line) and under

fully mutualised fund (solid line), EU28

Figure 9. Aggregate uncovered losses under mandatory reinsurance (dotted line) and under

fully mutualised fund (solid line), EU28

Mandatory reinsurance against mandatory lending

As regards comparing mandatory reinsurance and mandatory lending, additional statistics are

provided. Table 6 shows how the two models perform for in terms of uncovered liquidity shortfall and

25

uncovered losses. The table reports the share of simulations in which the better arrangement yields

lower uncovered liquidity and uncovered losses.

The relative performance of the two schemes with respect to uncovered liquidity shortfall and

uncovered losses crucially depends on the parameters underlying the mandatory reinsurance scheme.

As expected, parameters with lower caps of available reinsurance funds are associated with a worse

performance of the mandatory reinsurance scheme compared to mandatory lending in the short

(uncovered liquidity shortfall) and in the long run (uncovered losses). However, when mandatory

reinsurance caps are high, the mandatory reinsurance delivers a better coverage than mandatory

lending of short term liquidity and long-term loss cover needs.

As regards the combination of the two caps, raising the share of liquidity shortfall that can be re-

insured (alpha) from 20% to 80%, while keeping y (cap on the coverage) at 20%, improves the

performance of the reinsurance arrangement so that mandatory reinsurance becomes broadly

comparable to mandatory lending. When y is set at 80%, raising alpha from 20% to 80% makes re-

insurance the preferred arrangement over mandatory lending. The above results are valid both under a

balanced split of funds between the central body and the national DGS (beta=50%) and under an

unbalanced split (beta=75% or 25%). Analogously to what happens when varying alpha, the

performance of re-insurance improves under larger y. However, even with y=80%, alpha needs to be

set at a larger value for reinsurance to outperform mandatory lending. In general, if either alpha or y

are set too low, no matter how large the other parameter is, mandatory lending will turn out to be

preferable under current arrangements.

Moreover, while mandatory reinsurance prevails for higher caps in most of the runs, there are also

two cases in which the mandatory reinsurance arrangement is strictly superior to the mandatory

lending arrangement, i.e. the latter is outperformed in 100% of the simulations. This occurs if the

central body is allocated half (beta=50%) or ¾ (beta=25%) of the funds, with caps on uncovered

liquidity shortfall (alpha) and uncovered loss (y) at 100% (i.e., full cover).

For long-term uncovered losses, the re-insurance arrangement turns out to be generally preferable for

higher caps of loss cover (for alpha at least equal to 60% or to 80% in case national DGSs are

allocated ¼ of the resources), when the recovery rate is set at 90% for all the countries (see Table 7).

This is in line with the fact that increasing the amount of resources available at European level makes

the reinsurance arrangement absorb more losses. However, if the simulation uses recovery rates of

individual Member States (with an increase of 30% to take into account the new BRRD priority for

DGS claims), the mandatory reinsurance arrangement performs better even with higher caps of loss

coverage only (see Table 6). This might be due to the fact that banks with more distressed balance

sheets tend to be in countries where the legal framework is more uncertain.

26

Table 6. Mandatory reinsurance vs mandatory lending with individual MSs' recovery rate

(increased by 30% to factor in the BRRD priority for DGSs' claims)

Table 7. Mandatory reinsurance vs mandatory lending with recovery rate = 90%

It should be noted that if losses are very small, the share borne by the central body under re-insurance

may turn out to be lower than the funds initially contributed by the national DGS to the central fund.

In line with any insurance mechanism, the insurance premium may turn out to be larger than the

payout, if the event triggering coverage is associated with a small enough loss. This is consistent with

the fact a European reinsurance mechanism should be most effective for systemic events and should

Preferred

scheme

Share of simulations in

which the preferred

scheme outperforms the

competitor

Preferred

scheme

Share of simulations in

which the preferred

scheme outperforms the

competitor

alpha = 20%, y = 20%

ML 68% R 73%

alpha = 20%, y = 80%

ML 57% R 73%

alpha = 80%, y = 20%

R 52% R 97%

alpha = 80%, y = 80%

R 73% R 97%

alpha = 60%, y = 60%

R 59% R 93%

alpha = 100%, y = 100% R 98% R 100%

alpha = 20%, y = 20%

ML 74% R 52%

alpha = 20%, y = 80%

ML 66% R 52%

alpha = 80%, y = 20%

R 50% R 85%

alpha = 80%, y = 80%

R 66% R 85%

alpha = 60%, y = 60%

R 57% R 81%

alpha = 100%, y = 100% R 100% R 100%

alpha = 20%, y = 20%

ML 82% ML 65%

alpha = 20%, y = 80%

ML 77% ML 65%

alpha = 80%, y = 20%

ML 62% R 74%

alpha = 80%, y = 80%

ML 51% R 74%

alpha = 60%, y = 60%

ML 59% R 66%

alpha = 100%, y = 100% R 100% R 100%

beta = 75%

(0.6% to DGS -

0.2% to CB)

beta = 50%

(0.4% to DGS -

0.4% to CB)

beta = 25%

(0.2% to DGS -

0.6% to CB)

Re-insurance parametrization

Liquidity

Loss

Preferred

scheme

Share of simulations in

which the preferred

scheme outperforms the

competitor

Preferred

scheme

Share of simulations in

which the preferred

scheme outperforms the

competitor

alpha = 20%, y = 20%

ML 68% ML 55%

alpha = 20%, y = 80%

ML 57% ML 55%

alpha = 80%, y = 20%

R 52% R 88%

alpha = 80%, y = 80%

R 73% R 88%

alpha = 60%, y = 60%

R 59% R 84%

alpha = 100%, y = 100% R 98% R 100%

alpha = 20%, y = 20%

ML 74% ML 84%

alpha = 20%, y = 80%

ML 66% ML 84%

alpha = 80%, y = 20%

R 50% R 73%

alpha = 80%, y = 80%

R 66% R 73%

alpha = 60%, y = 60%

R 57% R 67%

alpha = 100%, y = 100% R 100% R 100%

alpha = 20%, y = 20%

ML 82% ML 97%

alpha = 20%, y = 80%

ML 77% ML 97%

alpha = 80%, y = 20%

ML 62% R 55%

alpha = 80%, y = 80%

ML 51% R 56%

alpha = 60%, y = 60%

ML 59% ML 53%

alpha = 100%, y = 100% R 100% R 100%

beta = 25%

(0.2% to DGS -

0.6% to CB)

beta = 75%

(0.6% to DGS -

0.2% to CB)

beta = 50%

(0.4% to DGS -

0.4% to CB)

Re-insurance parametrization

Liquidity

Loss

27

provide incentives for local banks and regulators not to use it for small interventions, whose necessity

for the stability of the financial system can be hardly assessed by the central body.

Finding #1. The fully mutualised fund offers greater protection than both the mandatory reinsurance

and the mandatory lending arrangements in all simulations, both in the short term (uncovered

liquidity) and in the medium/long term (uncovered losses). In the short term, the fully mutualised fund

makes more funds available, compared to the alternatives.

Finding #2. In the medium-long term, the probability of uncovered losses, implying failure of the

DGS itself, is the smallest under the fully mutualised fund, as extraordinary contributions are not

used to repay loans, as in the case of mandatory lending, but to cover losses. Under re-insurance, the

participation of the central body to the losses is capped.

Finding #3. As for the comparison between mandatory lending and mandatory reinsurance,

mandatory reinsurance is better able to cover liquidity needs in the short term or losses in the

medium-long term provided that sufficient re-insurance funds are made available.

Finding #4. The performance of mandatory reinsurance depends on the interplay between allocation

to the central body and the caps applied to resources made available by the central body to the

individual DGSs. Larger allocations from the central body obviously imply larger shares of liquidity

and losses which can be centrally covered.

Assessing diversification of risks under the three alternative arrangements 3.4.2.

The first part of the following assessment measures the implications for risk diversification in

moving from a solution with partial risk sharing (such as reinsurance or mandatory lending) to an

environment with full risk sharing (such as full mutualisation). Indeed, as risk sharing grows, there is

an increasing risk diversification across the participating Member States. The following formula

(developed in Annex 6.1) demonstrates that a mutualised DGS can make full use of risk

diversification to minimise the expected losses for bank i in country j (

It should be noted that the reinsurance and mandatory lending arrangements assume the collection of

contributions from national DGSs, based on the risk profile of banks within their local banking

systems. Within a mutualised arrangement the contributions of banks are calculated on the basis of