1 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

Nov. 14, 2017

RESEARCH REVIEW

The State of Latino Early

Childhood Development:

A Research Review

Authors

• Amelie G. Ramirez, Dr.P.H., Director, Salud America!, Professor, Institute for Health

Promotion Research, UT Health San Antonio

• Kipling J. Gallion, M.A., Deputy Director, Salud America!, Professor, Institute for Health

Promotion Research, UT Health San Antonio

• Rosalie Aguilar, M.A., Deputy Director, Salud America!, Professor, Institute for Health

Promotion Research, UT Health San Antonio

• Jennifer Swanson, M.Ed., JS Medical Communications, L.L.C.

About this Research Review

This report is copyright 2017 RWJF, Route 1 and College Road, P.O. Box 2316, Princeton, NJ,

08543-2316, www.rwjf.org

.

Abstract

Many Latino children are at risk of not receiving the proper care, services, and environment they

need during their formative years to promote healthy development.

Traumatic early childhood experiences, poor nutrition, physical inactivity, low participation in

preschool programs and early education, complex family and maternal structures, and other

factors have been shown to affect or impair Latino children’s social and emotional development,

academic achievement, and overall health and wellbeing.

Culturally sensitive programs and policies are increasingly needed to address the issues that

hinder healthy early development in Latino children.

Waiting for kindergarten is too late, because 90 percent of brain development occurs by age 5.

2 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

This research review summarizes the current literature on Latino child development and the

programs and policies for improving early childhood development in Latino children.

Introduction

Childhood development is a dynamic, interactive process that is not predetermined by genetics,

but is hindered by lack of proper care, services, and support. Proper childhood development is

critical because 90 percent of brain development occurs by age 5.

Latino childhood development is particularly important because Latinos make up 26 percent of

US children younger than 5. The Latino population is one of the fastest-growing U.S.

demographics, yet 12 million Latinos live below the poverty level.

1–3

As such, many Latino

children are at risk of not receiving the care and services they need during their formative years,

which may have negative effects on their early development and long-lasting consequences into

their adulthood. Less than half of kids from low-income families are starting kindergarten ready

to learn, compared to three-fourths of kids from middle-income families.

4

For example, although research has shown the many health, social and emotional, and

cognitive benefits of high-quality preschool programs, U.S. Latino children have the lowest

participation in these programs among the major racial and ethnic populations (Figure 1).

5,6

Less than half of Latino children are enrolled in any early learning program and for those who do

attend, program quality varies widely.

7

Poverty confounds participation in quality early learning

programs.

Figure 1. Preschool Participation Rates in the U.S., by Race/Ethnicity

5

Lack of participation in preschool programs, in combination with other factors such as infrequent

exposure to preliteracy activities at home, has led to reduced school readiness in Latino children

3 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

that may result in poor long-term outcomes.

5,6

Lack of participation may stem from lack of

availability. In a study about the location of child centers across eight states, 42% of children

younger than 5 live in areas known as child care deserts, which either have no child care

centers or so few centers that there are more than three times as many children as there are

spaces in centers. The availability of child care centers is in a state of crisis for Latino families.

More information about families’ proximity to child care programs can inform local, state, and

federal efforts to increase access to early childhood programs.

Early childhood experiences in school and at home have the potential to shape child

development, both positively and negatively. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are of

particular concern as they can lead to a multitude of issues that can affect individuals for a

lifetime. Many children, including Latino children, have been exposed to ACEs that have in

some way impaired their socioemotional development, academic achievement, and overall

health and wellbeing.

8,9

Other factors affect the healthy development of Latino children. Children living in underserved

areas have limited access to healthy food. Poor nutrition can lead to a host of issues including

poor physical health and cognitive difficulties. Limited access to fruits and vegetables, and

overconsumption of fast foods and unhealthy snacks, can lead to overweight and obesity—a

growing area of concern for Latino children

10

—that increases their risk of poor long-term

outcomes in many developmental areas including physical and mental health, education,

psychosocial functioning, and future socioeconomic status.

11

Despite the disparities mentioned above, many Latino children have been shown to have

healthy social and emotional development, and these qualities may help to attenuate some of

the negative effects of their disadvantages.

1,12

Therefore, preserving and improving upon these

socioemotional strengths is crucial for ensuring healthy early childhood development in Latino

children.

Moreover, more than 400,000 Latino children younger than 4 were not counted in the 2010 U.S

Census.

13

Ensuring Latinos are accurately counted in the 2020 Census is important for ensuring

equitable investment for healthy early childhood development in Latino children.

This research review summarizes the current literature on the issues mentioned above and the

programs and policies for improving these areas of early childhood development in Latino

children.

Methodology

For this research review, electronic searches of PubMed, Google, Google Scholar, and

government and organization websites were performed to identify literature that was relevant to

early childhood development in Latino children.

Combinations of the following MeSH terms were used: “Latino,” "Hispanic Americans"[Mesh],

"Mexican Americans"[Mesh], "Child"[Mesh], "Policy"[Mesh], "Public Policy"[Mesh], "Policy

Making"[Mesh], "Health Policy"[Mesh], "Infant"[Mesh], "Child, Preschool"[Mesh], "Growth and

Development"[Mesh], "Child Welfare"[Mesh], and "Infant Welfare"[Mesh]. Keywords included

adverse childhood experiences, Latino, Hispanic, American, children, social, emotional,

development, parenting practices, education, depression, school, preschool, Head Start, and

teachers.

4 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

Included in this review were studies, expert commentaries, and policy statements addressing

important aspects of early childhood development in Latino children, including disparities versus

other races and ethnicities, factors associated with healthy and unhealthy development, and

practices, programs, and policies for improving early childhood development in this population.

Exclusion criteria included articles written in non-English language and studies conducted

outside the United States. No limits were placed on publication date, but because of the breadth

and depth of the topic, only the most recent and relevant literature was included. Older studies

were included if they were deemed exceptionally important and relevant to current times. From

the initial search results, titles and abstracts were reviewed for relevance and cross-checked

against inclusion/exclusion criteria. Full text was obtained for relevant articles meeting the

inclusion criteria. Additional literature was found through hand searches of the bibliographies of

articles captured through the initial electronic searches. Research on non-Latino children and

older Latino children was included if deemed exceptionally important and potentially relevant to

Latino children in some way.

Key Research Results

• Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) interfere with healthy early childhood

development in Latino children. Programs and policies aimed at preventing ACEs and/or

mitigating their harmful effects may improve overall health and wellbeing in Latino

children.

• Latino children have limited access to healthy foods, which negatively affects overall

development and wellbeing. Improving access to healthy foods at home, at school, and

in the neighborhood/community may improve health, development, and wellbeing in

Latino children.

• Latino children also have limited access to active spaces—such as trails, parks, and

recreation facilities—that may prevent them from engaging in adequate levels of physical

activity for healthy development. Improving access to active spaces may improve

physical activity and health and wellbeing.

• Latino children have low participation in high-quality preschool programs and face

educational disadvantages when starting kindergarten.

• Latino families share many common values—such as familism and marianismo—that

may benefit Latino childhood development and influence early childhood development

programs.

• Early childhood development programs that have long-term benefits for other minority

and low-income children also likely benefit Latino children.

• Family-, preschool-, and community-based interventions may help to improve school

readiness and lead to better developmental outcomes for Latino children.

• Programs and policies providing maternal and breastfeeding support and family support

services promote healthy social and emotional development and overall wellbeing in

Latino children.

5 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

Studies Supporting Key Research Results

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) interfere with healthy early childhood

development in Latino children. Programs and policies aimed at preventing ACEs and/or

mitigating their harmful effects may improve overall health and wellbeing in Latino

children.

Growing up feeling safe, secure, and loved is essential for the healthy development of all

children,

14

yet 70% of all children are exposed to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) by age

6 that may have negative effects on many aspects of their developmental.

8,9,15

ACEs may

include parental domestic violence, substance abuse, mental illness, criminal justice

involvement, child abuse and/or neglect, poverty/homelessness, and parental death, among

others.

16

Multiple studies have shown that children exposed to ACEs are more likely to develop

physical, mental, behavioral, psychosocial, and/or cognitive issues than children who have not

been exposed to ACEs, and these effects can extend into adolescence and adulthood.

17–24

About 30 percent of Latino children in U.S.-native families reported two or more ACEs,

25

compared to 16 percent of Latino children in immigrant families. Unmeasured confounders may

buffer Latino children from exposure to ACEs in immigrant families, and/or negative effects of

unmeasured factors for Latino children in U.S.-native families. Also, questions about ACEs may

not capture the adverse experiences specific to immigrant families; in fact, it is possible that

adverse experiences and environments that are specific to the immigrant experience are not

reflected in traditional measures of ACE exposure. For both the native and immigrant groups,

parental divorce and economic hardship were the most prevalent ACE exposures. Poor

maternal mental health and single-woman family structure had the strongest associations with

ACE exposure in both groups. Similarly, in both groups, low-income or middle-income

households (≤200% of FPL or 201%–400%) were associated with twice the odds of exposure to

two or more ACEs compared with those from a high-income reference group.

Many studies have evaluated the multitude of effects of ACEs on Latino children specifically,

and these are categorized below by outcome measure.

Physical Health. The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL)

Sociocultural Ancillary Study evaluated ACEs in 5,117 Latino adolescents and adults (ages 18-

74) and found that 77.8% experienced at least one ACE, which stands in contrast to the 70% of

youth in general who are exposed to ACEs. The same study on Latino adolescents and adults

found that 28.7% experienced four ACEs or more.

26

Among the ACEs reported, the most

common were parental separation/divorce, emotional or physical abuse, and household

alcohol/drug abuse. After controlling for demographics and risk factors in this Latino population,

ACEs were found to be positively associated with multiple health-related conditions later in life,

including alcohol and tobacco use, coronary heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease, and cancer. Although this study did not find an association between ACEs and asthma,

another study that used 2011 to 2012 data from the National Survey of Children’s Health (N =

92,472; ages 0-17; 10.3% Latino) reported a 4.46 times increase in lifetime asthma among

Latino children experiencing four ACEs compared with those experiencing no ACEs.

Importantly, white children experiencing four ACEs had only a 1.19 times increase in lifetime

asthma.

27

Another study that used data from the HCHS/SOL Sociocultural Ancillary Study found that

economic hardship during childhood was associated with shorter height among Latinos

regardless of birth place and with greater adiposity in U.S.-born Latinos only.

28

Short stature and

adiposity may lead to chronic health issues later in life, but this study did not assess for those

6 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

associations in the adult participants. Further research is needed to understand the full effects

of childhood poverty on the development of chronic diseases in Latinos.

The Carolina Abecedarian Project (ABC) was designed as a social experiment to test if

stimulating the early care environment from birth to age 5 could prevent the development of mild

mental retardation in disadvantaged children.

29

Curriculum emphasized development of

language, emotional regulation, and cognitive skills, as well as caregiving, supervised play, two

meals, one snack, and primary pediatric care for the first five years of life. In their mid-30s,

participants had lower blood pressure, better lipid levels, and lower abdominal obesity. They

were less likely to have Metabolic Syndrome and had lower risk of experience Coronary Heart

Disease. Of participants and non-participants studied, those who are obese or severely obese in

their mid-30s are already on a trajectory of above-normal BMI in the first five years of their lives.

Children randomly assigned to stimulating early care from birth to age 5 had significantly lower

risk factors for cardiovascular and metabolic diseases in their mid-30s.

29

Mental Health. A study of data on youth from the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice (N =

64,329; 15.37% Latino) evaluated the effects of ACEs on suicide attempts, as mediated by

maladaptive behavior including personality development (aggression and impulsivity) and

problem behaviors (school difficulties and substance abuse).

30

Latino youth with higher ACE

scores were found to have significantly and directly increased odds of attempting suicide, as

well as school misconduct. Although Latino youth were less likely to experience ACEs and

attempt suicide than their white counterparts, they were more likely to have aggression, which

was a predictor of suicide. Efforts should be made to identify ACEs and

developmental/behavioral issues early to prevent potential suicidal behavior in Latinos and all

children.

Childhood maltreatment exposure was associated with mental health problems classified as

internalizing (anxiety, depression, withdrawal, somatic complaints) and externalizing

(delinquency, aggression) among Latino, non-Latino white, and black groups in one study of the

use of mental health services by children who had been exposed to some form of maltreatment

and were being investigated by child welfare services.

31

The study (N = 1,600; 19.3% Latino)

found that neither internalizing nor externalizing problems predicted the use of mental health

service in Latinos, which is contrary to previous findings suggesting that Latinos with

externalizing problems are just as likely to use mental health services as their white and black

counterparts.

32

The lack of significant association is potentially attributed to the smaller Latino

sample size in this study, as noted by the authors. However, other factors such as cultural and

family issues may dissuade Latino parents from following through on referrals made to mental

health services after their child’s exposure to maltreatment. Thus, additional research is needed

to identify the predictors of mental health service use among Latino youth and develop the

necessary assessment and counseling tools to identify at-risk Latino youth and get them the

mental health services they need to improve their mental health.

Read the full Salud America! research review on mental health and Latino children.

33

Substance Use/Abuse. A study of 1,259 Puerto Rican youth (10 or older at baseline) from the

South Bronx, New York and San Juan, Puerto Rico found that child maltreatment, parental

maladjustment, and sociocultural stressors increased the risk of early alcohol use (by age 14) in

this youth population.

34

Linear relationships were observed between the number of ACEs to

which a child was exposed and the risk of early drinking. Another study of 1,420 Latino

emerging adults in Southern California found that the presence of ACEs was significantly

associated with substance use or abuse, specifically cigarette, alcohol, marijuana, and hard

7 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

drug use. As the number of ACEs increased, so did the substance use for all substances.

35

Depressive symptoms stemming from ACEs can also increase the risk of substance use/abuse,

so identifying and treating depression may help to reduce the substance use/abuse, although it

is likely that many factors are involved and further symptoms assessment and intervention may

be warranted.

36

Education/achievement. Children ages 3 to 5 who have had two or more ACEs are over four

times more likely to have trouble calming themselves down, be easily distracted, and have a

hard time making and keeping friends. More than three of four children ages 3-5 who have been

expelled from preschool also had ACEs.

37

A study of urban children (N = 1,007; 24% Latino) used data from the Fragile Families and Child

Wellbeing Study, a national urban birth cohort, to evaluate the effects of ACEs on kindergarten

outcomes.

20

Children exposed to three or more ACEs were more likely to have below-average

language and literacy skills, poor math and emergent literacy skills, attention problems, and

aggression in kindergarten. However, the data were not analyzed separately for Latinos.

Preventing ACEs and/or mitigating their harmful effects is critical for improving prospects for

early child development, and many programs and interventions have been implemented in this

regard.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends early screening for developmental

and behavioral problems starting at age 9 months through 3 years.

38

The Birth to 5: Watch Me

Thrive! initiative is a federal effort to promote healthy child development through care

collaboration and a system-wide approach, and provides screening resources for families,

educators, and various healthcare providers (https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ecd/child-health-

development/watch-me-thrive).

39

Home visits have been also shown to help prevent ACEs by providing parents and caregivers

with the necessary support, knowledge, and tools to promote a healthy, nurturing home

environment for their children.

40

Proactively building trust, security, and resilience in families can

help children process and overcome the effects of ACEs should they occur. Home visitors

educate expecting and new parents about nutrition, sleep habits, and health care, do family and

child assessments to screen for ACEs (e.g., through family map inventories [FMIs],

41

and make

referrals to programs such as WIC, Medicaid, heat and housing programs, and domestic

violence services, as needed, to help them build a stable and healthy family. Moreover,

culturally-appropriate home visits that engage family and community members are especially

important for improving outcomes in Latino youth who may have mental health issues stemming

from ACEs or other reasons. For example, Project Wings Home Visits, a home visit program

aimed at improving mental health awareness among Latinos has shown progress in reducing

mental health issues in Latino youth.

42

Family-based home visit programs are especially

important for Latino families, as multiple family members may be living in the home and can play

an important role in promoting a healthy environment for Latino youth.

The pediatric medical home model, promoted by the AAP, has been studied as a potential

intervention to mitigate the harmful effects of ACEs. The medical home model is a continuous

and comprehensive approach to healthcare from infancy through young adulthood. In a study

using data from the 2011-12 National Survey of Children’s Health, children were evaluated for

physical and psychological health, social activities, educational achievement, ACE exposure

and medical home access.

43

8 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

Children were considered to have a medical home if they met the following criteria:

• Having a personal doctor or nurse

• Having a usual source for sick and well care

• Receiving family-centered care

• Getting referrals for specialty care when needed

• Having effective care coordination when needed

Medical home access was associated with greater wellbeing in children. Among children ages

6-11 who had experienced ACEs, access to a medical home resulted in higher levels of

wellbeing compared with no access to a medical home, suggesting that medical homes may

contribute to early ACE prevention, identification, and intervention. Importantly, children in

minority groups and those living in poverty or without insurance are less likely to have a medical

home than their white, more affluent, and insured counterparts,

44

so strategies for improving

access to a medical home in Latino children falling into these categories may be warranted.

Supportive relationships and teaching resilience skills can mitigate the effects of ACEs. Children

ages 6-17 who have had two or more ACEs but learned to stay calm and in control when faced

with challenges are over three times more likely to be engaged in school compared to peers

who have not learned these skills.

37

Other interventions for preventing, identifying and/or addressing ACEs may include screening

for ACEs during primary care visits and child welfare assessments, early care and education

(ECE), mindfulness-based, mind-body approaches, parent-child psychotherapy, and family

resilience programs, and quality and affordable childcare, among others.

40,45–51

ECE programs

and systems, for example, can provide trauma-informed care (TIC), which supports children’s

recovery and resilience using evidence-based approaches. A report by Child Trends identified

emerging TIC approaches: integrating trauma-informed strategies into existing ECE programs to

support children in those programs who have experienced trauma, building partnerships and

connections between ECE and community service providers to facilitate screenings of and

service provision to children and families; implementing professional standards and training for

infant and early childhood mental health consultants that emphasize TIC, and supporting the

professional development and training of the ECE workforce in working with and supporting

young children who have experienced trauma.

52

Regardless of the intervention used, cultural

sensitivity and relevance is important for addressing ACE issues that are specific to Latinos.

53

Latino children have limited access to healthy foods, which negatively affects overall

development and wellbeing. Improving access to healthy foods at home, at school, and

in the neighborhood/community may improve health, development, and wellbeing in

Latino children.

Pediatric obesity is an important public health issue. Targeted efforts to curb child obesity rates

are necessary, especially among Latino children, as this sub-group is more likely to become

overweight before entering elementary school than children of other ethnic groups.

11

Obesity in

Latino children increases health risk factors and can also impact school performance.

11,54

A main contributor of overweight and obesity in Latino children may be their limited access to

healthy food. See the full Salud America! research review on Latino children and healthy food

access here.

10

Some recent study results appear mixed on this issue. Although fast-food consumption does

occur in Latino children, one study found that their caloric intake from fast food was comparable

9 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

or lower than in other racial and ethnic groups, except for Asians.

55

Another study found that

soda and unhealthy snacks were commonly available in Latino households, but so were fresh

fruits and vegetables, and Latino preschool children also consumed fruits and vegetables more

frequently than black children.

56

These findings are somewhat contrary to those of another study

of primarily Latino and black children living in rural, low-income families in the Southeast US that

found lower consumption of fruits among Latinos compared with black children.

57

Many factors

appear to contribute to intake of fruits and vegetables, as another study of older Latino children

(ages 10-14) found that few of the participating children (N = 181) met the dietary

recommendations regard fruit and vegetable consumption and other nutritious food.

58

Access to

culturally-relevant healthy foods is also a factor. In a study of grocery stores in Latino and black

neighborhoods, most stores carried fewer than 50% of fruits and vegetables that were

considered culturally specific and commonly eaten by these populations.

59

Poverty and food

insecurity may play a contributing role as well,

60

as may parenting issues such as stress and

depression that may affect parental feeding practices.

61

Other issues such as cultural beliefs may influence the types of foods eaten. Many Latinos

believe they are lactose-intolerant and often avoid dairy products to reinforce this belief;

however, this culturally-specific eating preference may lead to deficiencies in micronutrients

such as calcium, potassium, and vitamin D. Optimal levels of these micronutrients are thought

to reduce the risk of heart disease, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes.

62

Because poor nutrition and obesity in Latino children is due to complex sociocultural reasons, a

broad approach to improving eating habits may be effective, especially when it includes

extended family networks, school, and community activities.

63

Addressing parent feeding

practices is necessary to empower Latino parents to offer healthier food choices at meal times

and snacks in the home environment. Parents should be encouraged to eat family meals

together to model healthy eating habits and to avoid TV during meals.

56

Early care and education (ECE) is an emerging setting for obesity-prevention via healthy

lifestyles. The use of ECE facilities—including child care centers, day care homes, Head Start

programs, preschool and pre-kindergarten programs—has become a norm in the U.S.

64

A

successful program, Color Me Healthy, demonstrated positive health outcomes in young

children as they learned about healthy eating and exercise in active ways, including interaction

with peers and parents. Additional programs that have been successful include Brocodile the

Crocodile, Eat Well Play Hard, and Hip Hop to Health, Jr.

65

Any program implemented,

however, should be modified as needed for cultural relevancy.

63

Several organizations play a central role in improving healthy eating in Latino children, including

schools, WIC, Head Start early child care programs, and churches. Community programs are

also effective. LA Sprouts, a 12-week hands-on nutrition/cooking and gardening curriculum was

pilot-tested with 104 Latino children (59% obese), with a control group, to increase knowledge

and skills on gardening, nutrition, and cooking.

66

The curriculum was developed to be culturally-

and age-appropriate for urban, Latino upper elementary children. At the end of the pilot test,

intervention children had significantly lower diastolic blood pressure and greater fiber intake

compared with controls; those who were overweight at baseline also had decreases in BMI and

weight gain compared with controls who were overweight. Another pilot study (led by a Salud

America! grantee) tested a community-based garden, nutrition, and cooking program, Growing

Healthy Kids, with a 60-percent Latino cohort of 120 children and their families. The study found

that 17% of overweight/obese children achieved an improved BMI classification. According to

parents’ reports, children ate two more servings of fruit per week and almost five more servings

of vegetables per week.

10 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

At the federal level, funding is allocated to schools to offer healthy breakfasts and lunches to

children who are on free or reduced meals, in which Latinos are more likely to qualify for than

white children. States with stronger nutrition standards are better able to reduce obesity among

children in free and reduced lunch programs. More innovative programs to improve nutrition in

schools include better vending machine choices and more nutritious a la carte items.

67

Other

federally-funded programs—such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP),

Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), Summer Food

Service, Head Start, and Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP)—may also help to

improve nutrition and access to healthy food in Latino children (see

https://www.nutrition.gov/food-assistance-programs

for more information);

68

importantly,

however, undocumented immigrant Latinos would not qualify for these programs and may need

help from other sources, such as emergency food assistance programs.

69

Latino children have limited access to active spaces—such as trails, parks, and

recreation facilities—that may prevent them from engaging in adequate levels of physical

activity for healthy development. Improving access to active spaces that promote

physical activity may improve health and wellbeing.

Many studies have found that U.S. Latino children have inadequate access to active spaces.

70–

75

One study of three diverse U.S. regions found that only 19 percent of Latino neighborhoods

had recreational facilities, compared with 62 percent of white neighborhoods.

76

Similar results

were found when looking specifically at neighborhood socioeconomic level, where children of

racial/ethnic minorities living in poverty had less access to active spaces than children living in

more advantaged neighborhoods.

77

Interestingly, national data found that Latino neighborhoods

were actually closer to parks but farther from green spaces than non-Latino neighborhoods,

78

so

more research may be needed to determine if and how the type of active space influences

physical activity levels.

Inadequate access to physical activity sites has been linked to low levels of physical activity

among Latino children.

79,80

In one study of children (66% Latino) living in East Harlem, NY,

nearly 80 percent of the Latino participants had no access to active spaces, and those living in

areas with fewer active sites spent less time engaging in physical activity. Therefore, increasing

access to active spaces in underserved areas may help to promote physical activity among

youth living there.

79,81,82

The Healthy People initiative developed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

aims to increase youth access to active spaces by improving the built environment (e.g., adding

sidewalks, bike lanes, trails, and parks) and increasing access to physical activity facilities.

83

Other initiatives are underway in a number of U.S. cities, many of which have predominantly

Latino communities. These include shared and open use policies, where schools and other

entities partner to share school recreational facilities with the public; outdoor learning

environments or green schoolyards, where early care facilities and schools include gardens and

natural elements in the playscape; Open Streets programs, where streets are closed to

motorized traffic allowing for safe use by residents for walking, bike riding, etc; “rails-to-trails”

projects, where inactive railroad tracks are converted into bike paths and parks in a number of

U.S. cities; opens space plans, which aim to improve access to trails and green space;

Complete Streets policies, which call for roadways to be safe and convenient for people of all

ages, whether walking, biking, driving, or riding transit; Vision Zero strategies,

84

which aim to

eliminate traffic fatalities and serious injuries; and other initiatives.

71,85–90

11 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

The design and development of communities can make it easier or more difficult for families to

be active on a daily basis. The National Physical Activity Plan highlights several methods to

increase families’ opportunities for incidental physical activity:

91

• Effective land use policies can put common destinations with walking and biking

connections near where families live, to increase active transportation as well as access

to vital community services.

• Community planners can integrate considerations for non-motorized travel and public

health into formalized planning processes, such as master plans, comprehensive plans,

zoning code updates, housing and commercial developments, metropolitan planning

organizations' (MPO) transportation improvement project lists, trail plans, and regional

transportation plans, with specific focus on improving environments in low-income

communities.

• Transportation spending can be reformed to tie it to larger goals for health, safety,

equity, and the environment—rather than to a focus only on traffic volumes and speeds.

Healthcare providers also play in important role in promoting physical activity. There is little

research on how effective physical activity counseling and prescriptions are to increase physical

activity levels among Latinos, but some studies show that asking patients about physical

activities levels is associated with weight loss, improved glucose control in diabetic patients and

increased physical activity among cancer survivors.

92

Additionally, physicians who are physically

active themselves are more likely to counsel more frequently and more effectively about the

importance of physical activity to their patients.

93,94

The National Physical Activity Plan highlights

the need for healthcare systems to integrate physical activity as a patient “vital sign” into

electronic health records for all healthcare providers to assess and discuss physical activity with

their patients.

91,92

Tobacco use, for example, was adopted as a vital sign 60 years ago. After

smoking, physical inactivity is the leading risk factor for predicting if a person will die early.

95

Healthcare systems should also support the capacity of school-based health clinics and early

learning programs to promote physical activity. Additionally, schools, childcare centers, and

early childhood facilities can adopt standards to ensure children are appropriately physically

active and to develop outdoor learning models to integrate physical activity, natural settings, and

education.

See the full Salud America! research review on Latino children and active spaces here.

89

Latino children have low participation in high-quality preschool programs and face

educational disadvantages when starting kindergarten.

Although Latino children may be of similar weight at birth and equally able to thrive in the first 2

years of life compared with white children,

96

their ability to reason and remember tasks

(cognitive processing skills), verbally communicate, and identify letters, numbers, and shapes

(preliteracy skills) lessens significantly by age 24 months, and these disparities appear even

more prevalent in Mexican-American children than in other Latino subgroups.

1

In general, a 15- to 25-percentage point gap exists for Latino children relative to their white

peers.

97

Children who start behind in kindergarten often stay behind. See more in the full Salud

America! research review on building support for Latino families.

98

Causes for cognitive, preliteracy, and oral communication gaps in Latino children are

multifactorial. Among the most common are poor education, large family sizes, low employment

or having multiple jobs, and depression among Latina mothers. These factors have been

12 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

suggested to reduce the likelihood that Latino parents would engage their children in preliteracy

activities or read books to them, both very important activities leading to literacy and school

readiness.

1,99,100

Although most Latino parents are bilingual or can speak English fairly well,

some do not have a good command of the English language, which may decrease their

likelihood of reading or telling stories to their children in English, compared with white

parents.

100,101

Additionally, cultural beliefs that teachers are the experts in these areas, coupled

with limited parental education, may deter Latino parents from engaging their child in preliteracy

activities.

Participation in preschool programs is also suboptimal in Latino children and is a main

contributor to poor school readiness.

5,6

In recent years, several programs have been set forth to

improve kindergarten readiness and create a trajectory of academic achievement, employment,

and increased earnings for disadvantaged Latino children.

In the United States, almost 70% of 4-year-old children go to early learning centers.

102

However, nearly six of every 10 4-year olds are not enrolled in publicly funded preschool

programs, and even fewer are enrolled in the highest-quality programs. Participation is

particularly low for Latino children, at 40% compared to 53% of white children. Participation is

also low for low-income children, at 41% compared to 61% of their more affluent peers.

7

Lack of participation in early care and education programs may stem from lack of availability. In

a study about the location of child centers across eight states, 42% of children younger than age

5 live in areas known as child care deserts, which either have no child care centers or so few

centers that there are more than three times as many children as there are spaces in centers.

103

The availability of child care centers is in a state of crisis for Latino families. Several elements

are critical for the ideal child care center:

• High-quality early childhood education centers should be more affordable and accessible

to low-income Latinos, with higher density in Latino neighborhoods.

104

• Early childhood education centers should offer services from birth through age 5 to allow

single-site care of all children within one family, and continuity of cognitive assessments

and interventions.

104

• The location and design of early learning centers can support active transport and

increased student physical activity throughout the school day.

91

• Students who have access to nature at school engaged in physical activity 10 times

longer than those students who had limited access to nature at school.

105

Outdoor

learning environments and green schoolyards, for example, can boost student’s

academic performance, physical activity, mental health, and different types of play,

which are critical for development.

• The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) states that unstructured free play is

essential for children’s emotional development and can protect against stress, anxiety

and depression in children.

106

More information about families’ proximity to child care programs can inform local, state and

federal efforts to increase access to early childhood programs, especially given the financial

impact of early care and education programs. Only 14% of public education dollars are spent on

early childhood education, yet for every $1 spent expanding early learning, society receives a

return on investment of $7 or more based on increased school and career achievement, as well

as reduced costs in remedial education, health, social welfare programs, and criminal justice

system expenditures.

5,7,107,108

13 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

Family-, preschool-, and community-based interventions may help to improve school

readiness and lead to better developmental outcomes for Latino children.

Many children attend Head Start programs, which were founded to promote school readiness

for children of low-income families. In recent years, the Head Start curriculum has been

challenged to enhance children’s language and preliteracy skills using interactive reading with

active discussions. One of these programs, the Research-based, Developmentally Informed

(REDI) classroom intervention, uses evidence-based curricula that center on preschool

attainment of language, preliteracy, and social-emotional skills considered essential for later

achievement. In a study of 356 children (17% Latino) enrolled in Head Start programs, children

exposed to the REDI intervention had significantly improved vocabulary and social-emotional

skills compared with those who were not exposed to the REDI intervention,

109

and these skills

were sustained throughout kindergarten.

110

REDI-P, the parent program of the REDI, was

introduced to teach parents to engage their children in directed talk and play sessions and

included bi-weekly home visits. In two randomized controlled trials (N = 200, 19% Latino;

111

N =

556, 19% Latino);

102

children exposed to both REDI and REDI-P showed significant gains in

literacy and social-emotional skills compared with children not exposed to both interventions,

and these gains were sustained into kindergarten

112

and second-grade, with improved

classroom participation, student-teacher interactions, and friendships.

102

Another randomized

study (N = 200; 20% Latino) showed similar findings but also found that REDI-P was

augmented by pre-intervention parental support for learning, with children receiving greater

baseline parental support faring better, suggesting that parental support is a key contributor to

child learning in preschool programs.

112

The Miami School Readiness Project (MSRP) was a large public preschool program that

examined the effects of preschool curricula on kindergarten readiness in 7,045 Latino children

(and 6,700 black children).

113

The program involved the use of two different curricula: the more

conventional and widely used High/Scope curriculum, which balances child-initiated and

teacher-directed activities in small- and large-group settings, and the Montessori curriculum,

which individualizes learning to each student and fosters independent, child-directed learning

with fewer teacher-directed activities. Although all children made progress in pre-academic,

socioemotional, and behavioral skills regardless of curriculum, the Montessori program

appeared to be more beneficial for Latino children who, despite being at the highest pre-

academic and behavioral risk at baseline, finished the preschool year with test scores above the

national average. One potential reason that the Montessori program was such a success in

Latino children is that it incorporates a child’s culture into the classroom, which some say is

essential for preschool success in Latino children. And, since black children seemed to fare

better in the High/Scope program, these data suggest that preschool curricula should be tailored

to racial, ethnic, and cultural differences. It has also been suggested that Montessori teachers

may be more educated and more culturally aware than teachers of other preschool programs,

which may be another contributor to the positive findings in this study.

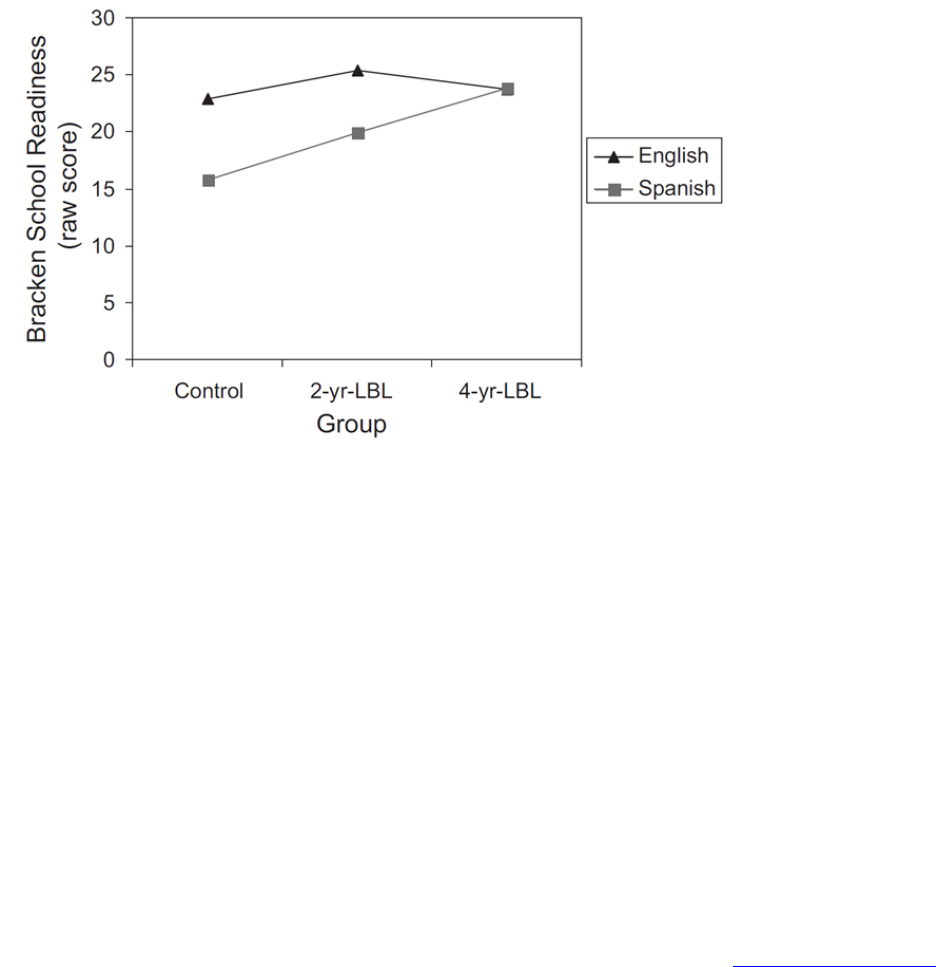

The Little by Little (LBL) program is a bilingual literacy promotion and supplemental nutrition

program provided as part of the WIC program. In LBL, parents receive brief counseling on the

importance of reading to and verbally interacting with their children, handouts on developmental

milestones and appropriate interaction methods for promoting optimal child development, and

an age-appropriate children’s book or toy for use during parent-child interactions. Reading

materials are provided in English or Spanish, depending on the family’s primary language. LBL

was implemented in Los Angeles, California, in 118,000 3- to 4-year-old, predominantly Latino

(92%) children in the WIC program; its effectiveness on kindergarten readiness was evaluated

14 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

by randomly selecting WIC families and dividing them into three groups based on their exposure

to the intervention: no intervention, 2-year intervention, and 4-year intervention.

100

Parents in the

intervention groups received the intervention when children were 2 years old (2-year

intervention) or when the mothers were in their third trimester of pregnancy (4-year

intervention). Although no significant differences were observed between intervention groups

among English-speaking families, Spanish-speaking families received significant benefit from

the intervention. Children in both intervention groups were significantly more prepared for

kindergarten (measured by Bracken School Readiness score) than those in the no intervention

group, with the 4-year group receiving the greatest benefit (Figure 2). The program also

improved the awareness in Spanish-speaking parents of the importance of promoting early

reading and verbal interaction with their children and providing a literature-rich home

environment to improve their child’s literacy skills and school readiness.

Figure 2. Effect of LBL Intervention vs Control on School Readiness in English- and Spanish-

Speaking Preschool Children

100

ParentCorps, another preschool program that involves both school-based and parenting-

centered interventions, aims to promote safe, nurturing, and predictable environments for

children. The program involves professional development for preschool teachers and parent

counseling administered by teachers and mental health professionals during after-school hours.

ParentCorps was evaluated in a randomized study of 4-year-olds (N = 1050; 9.8% Latino) from

99 preschool programs in New York City.

114

By second grade, children in this program had

fewer mental health problems, better student-teacher interactions, and higher academic

performance than peers who did not receive this intervention. Other examples of interventions

aimed at improving school readiness in Latino children include home visits, “Zero to Three”

programs, Pre-K 4 San Antonio, and First 5 LA.

2,115–118

Latino men are often less willing to talk about their problems, like parenting insecurities or health

issues, which can result in decreased engagement in their children’s life and decreased

attendance in parenting programs, which may hinder early childhood development. Researchers

in New York created a parenting class for 126 low-income, Spanish-speaking Latino dads, but

framed it as an academic-readiness program for children.

119

The eight-week training

intervention, which revolved around shared book reading, increased Latino dads’ parenting

15 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

skills by 30 percent, and increased Latino children’s language development and school

readiness by 30 percent. Additionally, the 79-percent parent attendance rate was high,

researchers indicated. The finding suggests it is critical to develop culturally relevant, engaging,

and sustainable parenting interventions for Latino fathers.

Teaching social and emotional skills can also have an impact on student’s academic

development. Social and emotional learning is “the process through which children and adults

acquire and effectively apply the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to understand and

manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish

and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions,” according to a Penn State

and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation report.

120

The report indicates that, when learned early,

social and emotional skills can help children overcome challenges and avoid unhealthy

behavior, improving a variety of outcomes into adulthood, and have significant economic impact

for individuals and society overall. The report cites research that indicates that students with

strong social and emotional skills: do better in school; are more likely to graduate college and

get a well-paying job; support healthy functioning and help people avoid problems like crime and

substance use; and have a greater likelihood for long-term success as an adult. Another report

indicates that evidence-based programs can optimize the teaching of social and emotional skills

in preschool through professional development for teachers, apparent involvement, and

integration with academic enrichment initiatives, which can spur greater benefits for children

with delays in social-emotional skill development associated with early socioeconomic

disadvantage.

121

Much of the Latino-focused research in this area specifically involves social and emotional

development in Spanish and English dual language learners.

122

Still, one study found that

teaching social and emotional skills to inner-city students contributes to their academic

achievement. The study involved all students enrolled in regular or bilingual education in an

inner-city school system where 2 out of 3 students qualified for a free or reduced price lunch

and 9 out of 10 students were black or Latino.

123

Another study found that classroom programs

designed to improve elementary school students’ social and emotional skills can also increase

reading and math achievement, even if academic improvement is not a direct goal of the skills

building. The benefit held true for students who qualified for free and reduced-priced lunch.

124

Early childhood development programs that have long-term social and emotional

development benefits for other minority and low-income children also likely benefit

Latino children.

Children who participate in high-quality early care and education (ECE) programs experience a

range of immediate and long-term cognitive and health benefits, with the greatest impact seen

in low-income populations.

98

Although extensive literature is available on the long-term effects of Head Start and other early

childhood development programs on black and white children, the effects of these programs on

Latino populations have mostly been ignored.

125

Additionally, nearly 40 years ago, it was

recognized that cultural differences exist among the different Spanish-speaking people and that

different subgroups should be analyzed separately. However, early data from Head Start

centers tended to combine all Latinos into one group.

125,126

From the available data, providing Spanish language in preschools was shown to enhance

Latino and non-Latino education as far back as the 1980s, and current recommendations

believe that Spanish language and culture should be instituted in preschool programs serving

16 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

Latino communities.

126–128

The Head Start Curriculum is mandated to have at least one Spanish-

speaking educator, and that educator should be able to understand a Latino child’s culture and

heritage.

125

Although long-term effects of the Head Start program were not documented for

individual children or for Latinos specifically, an overall cost-benefit impact was found in social,

emotional and health outcomes.

129–132

White children who attended Head Start were more likely

to complete high school and attend college than their siblings who attended regular preschools.

For black children, there were less significant educational gains from attending Head Start

versus a regular preschool, but a decrease in criminal activity was observed.

133

The long-term effects of other preschool and elementary programs on low-income, but not

necessarily Latino, populations are mentioned herein to sort out factors that led to successful

outcomes in children attending these programs. The Child-Parent Center program in Chicago

provides educational enrichment through school- and family-based services from preschool to

third grade. In this program, parent involvement was mandatory, teachers interacted with

parents directly, and classroom sizes were small, all of which contributed to its success.

134

Compared with children who did not participate in the program, those who participated in the

preschool phase of the program were more likely to graduate high school, attend a 4-year

university, and have more overall years of education. Those participating in the preschool and

grade school phases had higher rates of full-time employment and educational attainment.

Other long-term benefits of the program included increases in attainment of health insurance,

reductions in depression and disability, and reductions in criminal activity and arrests.

The High/Scope Perry Preschool Program was implemented for 123 low-income black children

who were followed up from preschool to age 40. Those participating in the program showed less

criminal activity, greater earnings, higher rates of high school graduation, and higher IQs

compared with those who did not.

135

The Project STAR program enrolled children between

kindergarten and third grade and showed that improved test scores, and higher earnings,

college attendance, home ownership, and 401(k) savings at age 27, were due to noncognitive

skills learned in high-quality kindergartens. They also showed that smaller and better classroom

environments for grades 5-8 resulted in marked long-term benefits even without earlier

intervention and that students from smaller classes (13-17 children vs 20-25 children) were

more likely to attend college.

136

Finally, the Abecedarian Project cared for and educated children

from as young as 6 weeks to 8 years. Enrollment in the program led to better educational gains,

mixed economic benefits, and no difference in social-emotional measurements compared with

not being enrolled in the program.

137

Taken together, the most successful elements in these studies—smaller class sizes, more

parent involvement, and better-educated teachers—would likely benefit Latino children as well,

if implemented in Latino-focused programs. Importantly, these programs were more expensive

to run than the Head Start programs.

Latino families share many common values—such as familism and marianismo—that

may benefit Latino childhood development and influence early childhood development

programs.

Children begin to develop their social and emotional skills through initial interactions with family.

Through strong and consistent relationships, they learn the importance of social bonding,

connecting to others with empathy, and self-regulating emotions. Young children begin to learn

about complex social interactions by receiving responsive caregiving from parents, which often

leads to positive outcomes later in life. One study (N = 7,750; 19% Latino) found that although

Latino children may demonstrate cognitive gaps compared with white children after age 1, their

social-emotional health rivals that of white children, even when raised in lower-income families.

1

17 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

These findings suggest that social and emotional health of Latinos develops on an independent

pathway. One potential reason is the parenting style among Latina mothers, which can be

characterized as warm and nurturing. Latina mothers are typically very responsive to their

children, and report fewer depressive symptoms than white mothers, which could be allowing for

stronger connectedness with their children.

Common values can be found among most Latino families.

• The concept of family, or familismo, is extremely important to many Latinos. Family

needs come before individual needs, and this is evident in Latinos’ desire to center many

activities around the extended family.

138

Due to economic circumstances, Latino

households may be large and include members of the extended family, which can be

stressful in some cases and helpful in others, especially regarding childrearing.

• Traditional gender roles, machismo and marianismo, are often practiced in Latino

families, especially in low-income families.

139,140

Machismo refers to the idea that the

father is the head of the household, strong protector, and authority figure, whereas

marianismo means the mother is self-sacrificing, religious and responsible for raising the

children and maintaining the house.

141

• Religion is also a cornerstone of the family and influences many beliefs and decisions

within the family.

142

Most Latinos in the U.S. practice Catholicism, but practices within

that faith may differ depending on the country of origin.

143

Because religion has been a

part of Latino culture for so long, religious beliefs are difficult to separate from cultural

values and often guide Latinos in many areas of life, even if they are not practicing

religion.

142

Many of these common qualities of Latino families—strong familial bonds, religious and cultural

values, protective fathers and nurturing mothers—are beneficial for the development of Latino

children and should be considered in early childhood education and development programs.

Educators and community organizations should target programs to the entire family, including

the extended family when feasible, and to mothers as caregivers and fathers as important

decision-makers. Coordination with local religious institutions is also important to ensure that

religious beliefs and cultural values are considered in program development.

144,145

Programs and policies providing maternal and breastfeeding support and family support

services promote healthy social and emotional development and overall wellbeing in

Latino children.

Although Latino children are generally well adjusted socially and emotionally, several factors

may negatively influence their overall health and wellbeing development. These include poverty

and/or large households, immigration status, the country of origin, maternal depression,

1,146,147

as well as other factors like breastfeeding initiation and duration.

148

Read the Salud America! research review about breastfeeding among Latina mothers.

148,149

Approaches are emerging on how to address these issues. For example, mental health

interventions can be made available to Latina mothers who are displaying negative thought

patterns, including anxiety, depression, and self-doubt.

150

Providing outlets for mothers to talk

with peers and trained counselors and/or nurses may help to reduce stress and improve

intrapersonal awareness toward mental health and its effects on family and childrearing. In

particular, home-based interventions have been successful in this population.

129,130128,129

The

Latino family typically includes extended relatives, and sometimes friends, which may lead to

several people living in one household. Latina mothers may shoulder many responsibilities

18 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

because of the family structure. Involving family members, especially partners, in helping with

household responsibilities, including children’s activities, may reduce the load that mothers carry

in this culture.

127

Read the Salud America! research review about mental health and Latino

children.

33

Similarly, parent education classes could be offered to Latino parents to reinforce styles that are

responsive, positive, and warm. Innovative approaches may include meeting with families in the

home environment and learning about the challenges that exist from living with extended

families, often in small areas. Addressing specific parenting skills, such as skill encouragement,

monitoring discipline, and positive involvement), may be beneficial to immigrant parents.

131

Read

the Salud America! research review about building support for Latino families.

98

Conclusions and Policy Implications

Conclusions

Latino children are at increased risk of poor outcomes in many areas of early childhood

development. Factors such as socioeconomic status, parenting behaviors, family structure and

environment, childhood experiences, and access to early education programs and health

services can influence many aspects of child development. High-quality preschool programs,

parent-directed support and education, and family-, school- and community-based programs

have all been shown to improve developmental outcomes in Latino children. Preventing,

identifying, and helping children and families overcome ACEs can impact a child’s social

emotional development and chances of school success. Additional resources are needed to

develop new, culturally appropriate programs and policies and/or improve upon those already in

place, to further support Latino children in their formative years and beyond.

Policy Implications

To address adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among Latino children:

• Improve access to home visits for Latino families by engaging community advocates,

civil rights organizations, and other stakeholders who understand the needs in their

communities; ensure that home visit programs are equitable and culturally sensitive to

the needs of Latinos.

• Strengthen the childcare workforce through training to provide trauma-informed care for

ACEs.

• Increase awareness of and support for the medical home system of care for Latino

children that can help to identify and address ACEs and other health-related issues

early.

• Increase collaboration between child welfare agencies and early intervention programs

to provide mental health services to children experiencing difficulties due to ACEs.

• Develop culturally sensitive programs, policies and interventions considering Latino

family structure and dynamics.

• Allocate funding for early-life interventions including prenatal care and parent education

and support to prevent ACEs in at-risk families.

To extend the benefits of early care and education (ECE) and preschool programs:

• Promote access to and availability and awareness of preschool and early childhood

education programs, especially for Latino children given the lower participation rates, to

better address the cognitive gaps prevalent in this group.

19 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

• Incorporate culturally-relevant parent counseling, education, and support into all

preschool programs.

• Reduce classroom sizes to promote greater teacher-student interaction and

individualized education.

• Implement culturally-sensitive teacher education and training, especially targeted to

overcoming poor school readiness among Latino children.

• Increase parent involvement in classrooms and home visits by educators to ensure

reinforcement of preliteracy activities in the home.

• Ensure that at least one Spanish-speaking educator is present at preschools teaching

Latino children.

• Support adoption of school design strategies to support active transport and increased

student physical activity throughout the school day, such as outdoor learning

environments or green schoolyards.

To improve Latinos’ access to healthy food:

• Allocate funding to support community-based initiatives that improve access to grocery

stores, health food stores, and farmers’ markets in Latino communities.

• Partner with farmers’ markets to develop long-term strategies for improving access to

fresh fruits and vegetables in Latino communities.

• Increase access to culturally-appropriate healthy eating interventions and educational

programs or activities (i.e., gardening) for Latino children and their families.

• Improve Latinos’ access to school-, community-, and government-based food programs.

To increase Latinos’ access to physical activity spaces and opportunities:

• Improve access to active spaces (parks, trails, green space, recreation sites) in Latino

communities.

• Solicit community feedback to strengthen the development of new recreation sites and

improvements in the built environment.

• Implement Complete Streets transportation projects near affordable housing, schools,

grocery stores, and recreation sites to improve active travel to those sites.

• Construct affordable housing near public transit, employment centers, schools, grocery

stores, and parks.

• Improve outdoor learning environments and green schoolyards at childcare centers and

schools.

• Integrate considerations for non-motorized travel and public health into formalized

planning processes, such as master plans, comprehensive plans, zoning code updates,

housing and commercial developments, metropolitan planning organizations' (MPO)

transportation improvement project lists, trail plans, and regional transportation plans,

with specific focus on improving environments in low-income communities.

• Reform transportation spending at all levels to tie it to larger goals for health, safety,

equity, and the environment—rather than to a focus only on traffic volumes and speeds.

To improve Latinos’ healthcare access:

• Incorporate assessment of patients’ childhood history in routine primary care visits to aid

in the identification of presence or risk of ACEs, and implement culturally and

linguistically relevant interventions.

• Advocate for early developmental-behavioral surveillance and screening, according to

the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations.

• Provide home visiting to ensure parents and caregivers have the time, knowledge, and

resources needed to ensure proper childhood development.

20 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

• Incorporate physical activity as a patient “vital sign.”

• Support the capacity of school-based health clinics and programs to promote healthy

eating and physical activity.

Future Research Needs

Further research is needed to identify the barriers to healthy eating in Latino children and

evaluate current and new strategies for improving access and adherence to a healthy diet.

Studies should also aim to identify the determinants of ACEs in Latino families and evaluate

interventions for preventing ACEs and/or mitigating their harmful effects. The use of

administrative data, such as Medicaid claims and other service records, may be useful for these

studies and may help to target prevention and early intervention for children with or at risk of

ACEs. More research is needed to identify the barriers to and predictors of mental health

service use among Latino youth and develop the necessary assessment and counseling tools to

identify at-risk Latino youth. More research is needed to identify the barriers to preschool

participation and in-home preliteracy activities to inform the development of targeted in-home

interventions to improve school readiness in Latino children. Accurate census data is also

critical to ensure equitable distribution of funding for early educational programs, healthcare,

safe places to walk and play, access to healthy food, and maternal and breastfeeding

support. Additionally, further research is needed to evaluate the short- and long-term effects of

existing preschool programs, such as Head Start, REDI, and MSRP, especially for Latino

children, since this information is currently lacking. Finally, more research is needed to

determine parent and teacher qualities that lead to educational success in Latino children and to

evaluate strategies that promote the development of these qualities in Latino parents and

teachers who teach Latino children.

21 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

References

1. Guerrero, A. D. et al. Early Growth of Mexican–American Children: Lagging in Preliteracy

Skills but not Social Development. Matern. Child Health J. 17, 1701–1711 (2013).

2. Krogstad, J. M. Hispanics only group to see its poverty rate decline and incomes rise. Pew

Research Center (2014).

3. Proctor, B., Semega, J. & Kollar, M. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2015.

(2016). Available at: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2016/demo/p60-256.html.

(Accessed: 25th January 2017)

4. Isaacs, J. B. Starting School at a Disadvantage: The School Readiness of Poor Children.

Brookings (2001).

5. US Department of Education. A Matter of Equity: Preschool in America. (2015).

6. Yoshikawa, H. et al. Investing in our future: The evidence base on preschool education.

(Society for Research in Child Development, 2013).

7. White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for Hispanics. Early Learning: Access to

A High Quality Early Learning Program. Available at: https://sites.ed.gov/hispanic-

initiative/files/2014/05/WHIEEH-Early-learning-Fact-Sheet-FINAL_050614.pdf. (Accessed:

25th October 2017)

8. Braveman, P., Egerter, S., Arena, K. & Aslam, R. Early Childhood Experiences Shape

Health and Well-Being Throughout Life. (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2014).

9. Bright, M., Knapp, C., Hinojosa, M., Alford, S. & Bonner, B. The Comorbidity of Physical,

Mental, and Developmental Conditions Associated with Childhood Adversity: A Population

Based Study. Matern. Child Health J. 20, 843–853 (2016).

10. Perry, A., Patlak, M., Ramirez, A. G. & Gallion, K., J. Making Healthy Food and Beverages

the Affordable, Available, Desired Choices Among Latino Families. (2015).

11. Liu, G. C., Hannon, T., Qi, R., Downs, S. M. & Marrero, D. G. The obesity epidemic in

children: Latino children are disproportionately affected at younger ages. Int. J. Pediatr.

Adolesc. Med. 2, 12–18 (2015).

12. Galindo, C. & Fuller, B. The social competence of Latino kindergartners and growth in

mathematical understanding. Dev. Psychol. 46, 579–592 (2010).

13. Child Trends. Dissemination of Child Trends report: “The Invisible Ones: How Latino

Children Are Left Out of Our Nation’s Census Count”. Child Trends

14. Newton, J. Prevention of mental illness must start in childhood: growing up feeling safe

and protected from harm. Br J Gen Pr. 65, e209–e210 (2015).

15. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Early Childhood Experiences Shape Health and Well-

Being Throughout Life. (2014).

16. Lucenko, B. A., Sharkova, I. V., Huber, A., Jemelka, R. & Mancuso, D. Childhood adversity

and behavioral health outcomes for youth: An investigation using state administrative data.

Child Abuse Negl. 47, 48–58 (2015).

17. Bright, M. A., Alford, S. M., Hinojosa, M. S., Knapp, C. & Fernandez-Baca, D. E. Adverse

childhood experiences and dental health in children and adolescents. Community Dent.

Oral Epidemiol. 43, 193–199 (2015).

18. Burke, N. J., Hellman, J. L., Scott, B. G., Weems, C. F. & Carrion, V. G. The impact of

adverse childhood experiences on an urban pediatric population. Child Abuse Negl. 35,

408–413 (2011).

19. Flaherty, E. G. et al. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Child Health in Early

Adolescence. JAMA Pediatr. 167, 622–629 (2013).

20. Jimenez, M. E., Wade, R., Schwartz-Soicher, O., Lin, Y. & Reichman, N. E. Adverse

Childhood Experiences and ADHD Diagnosis at Age 9 Years in a National Urban Sample.

Acad. Pediatr. 17, 356–361 (2017).

22 Salud America! https://salud-america.org/

21. Kerker, B. D. et al. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Mental Health, Chronic Medical

Conditions, and Development in Young Children. Acad. Pediatr. 15, 510–517 (2015).

22. Mersky, J. P., Topitzes, J. & Reynolds, A. J. Impacts of adverse childhood experiences on

health, mental health, and substance use in early adulthood: A cohort study of an urban,

minority sample in the U.S. Child Abuse Negl. 37, 917–925 (2013).

23. Pretty, C., O’Leary, D. D., Cairney, J. & Wade, T. J. Adverse childhood experiences and

the cardiovascular health of children: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 13, 208

(2013).

24. Thompson, R. et al. Trajectories of Adverse Childhood Experiences and Self-Reported

Health at Age 18. Acad. Pediatr. 15, 503–509 (2015).

25. Caballero, T. M., Johnson, S. B., Buchanan, C. R. M. & DeCamp, L. R. Adverse Childhood

Experiences Among Hispanic Children in Immigrant Families Versus US-Native Families.

Pediatrics e20170297 (2017). doi:10.1542/peds.2017-0297

26. Llabre, M. M. et al. Childhood Trauma and Adult Risk Factors and Disease in

Hispanics/Latinos in the US: Results From the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of

Latinos (HCHS/SOL) Sociocultural Ancillary Study. Psychosom. Med. 1 (2016).

doi:10.1097/PSY.0000000000000394

27. Wing, R., Gjelsvik, A., Nocera, M. & McQuaid, E. L. Association between adverse

childhood experiences in the home and pediatric asthma. Ann. Allergy. Asthma. Immunol.