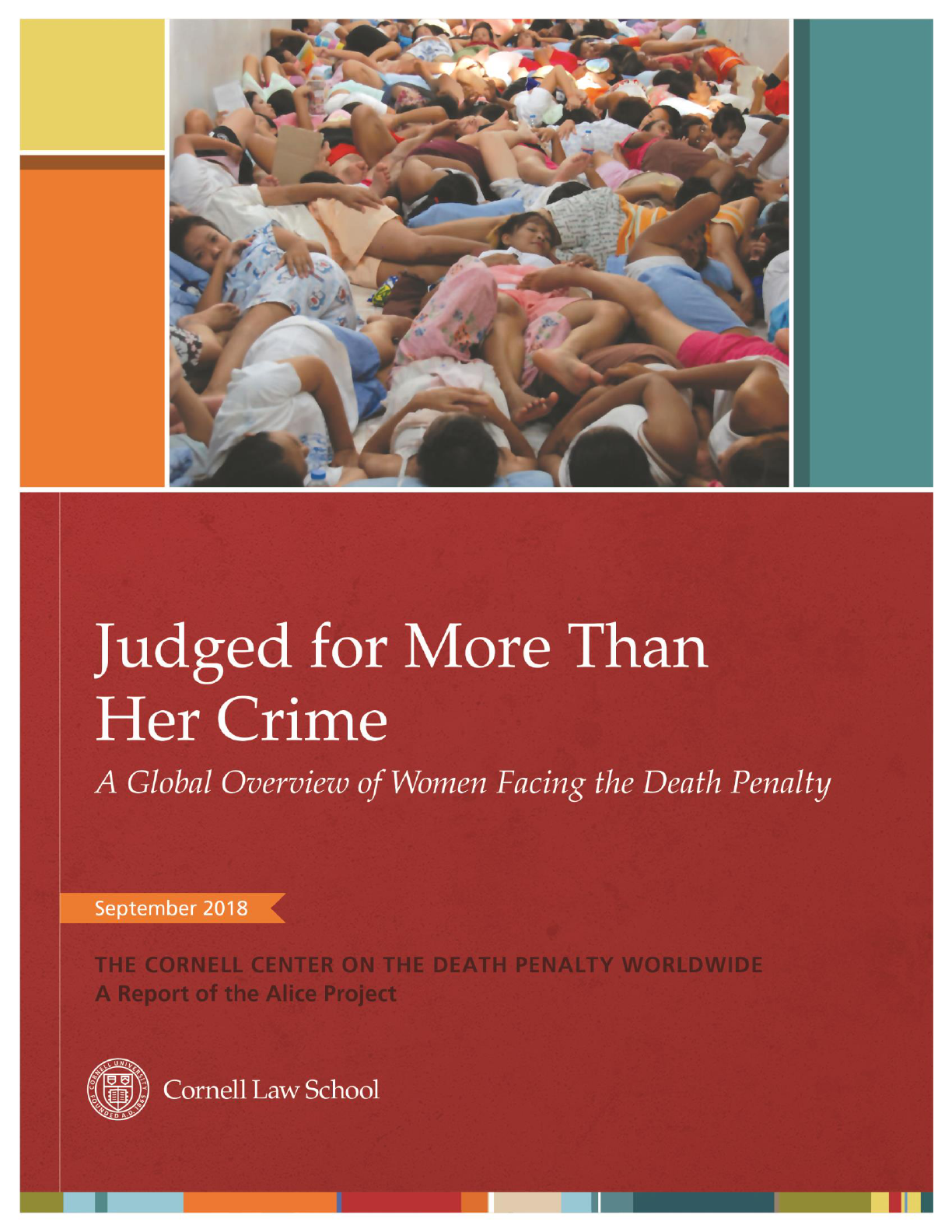

Judged for More Than

Her Crime

A Global Overview of Women Facing the Death Penalty

THE CORNELL CENTER ON THE DEATH PENALTY WORLDWIDE

A Report of the Alice Project

September 2018

THE CORNELL CENTER ON THE DEATH PENALTY

WORLDWIDE aims to bridge critical gaps in research and

advocacy around the death penalty. The Center provides

comprehensive, transparent data on the death penalty laws

and practices of all countries and territories that retain the

death penalty. It publishes reports and manuals on issues

of practical relevance to defense lawyers, governments,

courts, and organizations grappling with questions relating

to the application of the death penalty, particularly in the

global south. It also engages in targeted litigation and

advocacy focusing on the implementation of fair trial

standards and the rights of those who come into conflict

with the law, including juveniles, women, and individuals

with intellectual disabilities and mental illnesses. Finally,

it provides training through the Makwanyane Institute to a

cadre of competitively chosen Fellows, who undergo

intensive capital defense training with the intent to return

home and share their knowledge with other capital

defenders around the globe. More information is available

at www.deathpenaltyworldwide.org.

Copyright © 2018 Cornell Center on the Death Penalty

Worldwide. All Rights Reserved.

Table of Contents

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................................... 1

FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................................ 3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................ 4

I. INTRODUCTION: WOMEN ON DEATH ROW, INVISIBLE SUBJECTS OF GENDER DISCRIMINATION ............ 6

II. METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................. 9

III. WOMEN FACING THE DEATH PENALTY AROUND THE WORLD: AN UNDERSTUDIED POPULATION ........ 9

IV. CRIMES FOR WHICH WOMEN ARE SENTENCED TO DEATH ................................................................ 11

V. WOMEN IN VULNERABLE SITUATIONS FACING THE DEATH PENALTY ................................................. 15

VI. PRISON CONDITIONS FOR WOMEN UNDER SENTENCE OF DEATH ..................................................... 19

VII. COUNTRY CASE STUDIES ................................................................................................................. 24

India .................................................................................................................................................................. 24

Indonesia .......................................................................................................................................................... 26

Jordan ............................................................................................................................................................... 27

Malawi .............................................................................................................................................................. 29

Pakistan ............................................................................................................................................................ 30

United States of America .................................................................................................................................. 32

RECOMMENDATIONS ........................................................................................................................... 35

APPENDIX: INTERNATIONAL TREATY OBLIGATIONS OF PROFILED COUNTRIES ........................................ 37

ENDNOTES ........................................................................................................................................... 39

1

Acknowledgements

This report builds upon research conducted by Delphine

Lourtau in 2015 with the support of Cornell Law School’s

Avon Global Center for Women and Justice. The current

report was co-authored by Delphine Lourtau, Sandra

Babcock, Sharon Pia Hickey, Zohra Ahmed, and Paulina

Lucio Maymon. Katie Campbell, Julie Bloch, Kyle

Abrams, Cassandra Abernathy, Leigha Crout, Christine

Mehta, and Elizabeth Chambliss Williams provided

substantial research, writing, and editing. Many thanks to

Elizabeth Brundige for her keen understanding and early

support for the project. A very special thank you to our

partner, the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty,

and to Aurélie Plaçais for obtaining the resources

necessary to produce this report, and for her close

collaboration and expert guidance in the drafting of the

report. We are grateful to Aurélie for her constant support.

Cornell students Avery Cummings, Caroline Markowitz,

Grace Oh, and Xiaofei Xie provided substantial research.

We are grateful to Randi Kepecs for providing comments

and technical assistance.

The authors are immensely grateful to the many

individuals and organizations who shared their time,

knowledge, and insights with us. We are deeply indebted

to the individuals featured in our case studies, and their

families and lawyers for allowing us to present their

stories. We are very grateful to our local partners who

collected hard-to-find data and shared countless insights

in personal interviews. Without their contributions, this

publication would not have been possible. We are

particularly indebted to the following organizations and

individuals who conducted on-the-ground investigations

that informed the country chapters:

IN INDIA: Project 39A in National Law University, Delhi

undertakes research on various aspects of the criminal

justice system in India and also provides pro bono legal

representation to under-trial prisoners and those on death

row. It is formally a part of NLU Delhi and draws

inspiration from Article 39-A in the Constitution of India

on equal justice and equal opportunity. Project 39A

currently undertakes research on forensics, torture, legal

aid, forensic psychiatry, sentencing and the death penalty.

NLU Delhi started its engagement with the death penalty

through the Death Penalty Research Project and the

Centre on the Death Penalty between 2013-18, which has

subsequently transitioned into Project 39A for a broader

engagement with the criminal justice system in India.

IN INDONESIA: LBH Masyarakat is a not-for-profit non-

governmental organization, based in Jakarta, that provides

free legal services for the poor and victims of human

rights abuses, including people facing the death penalty or

execution; undertakes community legal empowerment for

marginalized groups; and advocates for law reform and

human rights protection through campaigns, strategic

litigation, policy advocacy, research and analysis.

IN JORDAN: Iyad Alqaisi is a practicing lawyer based in

Amman and the director of Justice Clinic, an NGO

focused on legal reforms. He is a member of the Jordan

Bar Association and the Palestinian Bar Association. An

Open Society Foundation Rule of Law Fellow, he holds

an LL.M from Syracuse University, New York and an

LL.B from Jordan’s Yarmouk University.

IN MALAWI: We relied heavily on data generated by the

Malawi Capital Resentencing Project, spearheaded by the

Malawi Human Rights Commission in collaboration with

the Cornell Law School International Human Rights

Clinic, Reprieve, the Paralegal Advisory Services

Institute, the Director of Public Prosecutions, Legal Aid,

the Malawi Law Society, Chancellor College of Law, and

the Malawi Prisons Service. Through this project,

paralegals, students, Reprieve Fellows, and volunteer

lawyers gathered mitigating evidence for more than 150

prisoners who had received mandatory death sentences.

After hearing this evidence in accordance with a new,

discretionary sentencing regime, the high courts released

131 prisoners; the rest received reduced sentences.

IN PAKISTAN: Justice Project Pakistan is a legal action

non-profit organization based in Lahore, Pakistan. It

provides direct pro bono legal and investigative services

to the most vulnerable Pakistani prisoners facing the

harshest punishments, particularly those facing the death

penalty, the mentally ill, victims of police torture, and

detainees in the War on Terror. JPP’s vision is to employ

strategic litigation to set legal precedents that reform the

criminal justice system in Pakistan. It litigates and

advocates innovatively, pursuing cases on behalf of

individuals that hold the potential to set precedents that

allow those in similar conditions to better enforce their

legal and human rights. Its strategic litigation is coupled

with a fierce public and policy advocacy campaign to

educate and inform public and policy-makers to reform

the criminal justice system in Pakistan.

IN THE UNITED STATES: Cassandra Abernathy is an

attorney with the law firm Perkins Coie LLP. Cassandra

focuses her pro bono practice on prisoners’ rights and

death penalty defense. Perkins Coie LLP generously

supported Ms. Abernathy to continue her work on women

on death row in the US through this project.

We are also grateful to the following experts for their

invaluable assistance: Teng Biao, Pamela E. Berman

(IANGEL), Danthong Breen (Thailand Union of Civil

Liberties), Katie Campbell, Sandrine Dacga, Vijay

Hiremath, Hannah Hutton (IANGEL), Yuliya

Khlashchankova (Belarus-Helsinki Committee), Juli King

(IANGEL), Cecilia Lipp (IANGEL), Yanan Liu, Nicola

2

Macbean (The Rights Practice), Hacene Mahmoud

Mbareck (Coalition mauritanienne contre la peine de

mort), Abdellah Mouseddad (Association marocaine des

droits humains), Tanya Murshed (Evolve), Kolawole

Ogunbiyi (Avocats Sans Frontières France), Hossein

Raeesi, Maiko Tagusari (Centre for Prisoners’ Rights),

Angela Uwandu (Avocats Sans Frontières France), and

Liang Zhang.

We also would like to thank Martha Fitzgerald, Justin

Gravius, and Katie Vaz from Cornell Law School’s

Communications department for their assistance with

designing the report.

Many thanks to Sofia Moro, Tom Short, and Kulapa

Vajanasara for the use of their photographs.

This publication was made possible with the generous

support of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway and

the Avon Global Center for Women and Justice.

We are honored that Dr. Agnes Callamard, Special

Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary

executions, contributed the foreword to this report, and

express our appreciation for the gender lens through

which she is implementing her mandate.

The authors’ views do not necessarily reflect the views of

either the Norwegian government or the individuals

interviewed over the course of the project.

3

Foreword

There is no place for the death penalty in our societies. It

trivializes justice and redress. It legitimizes and legalizes

revenge. It does not deter crime. It is cruel, inhuman and

degrading in its implementation. It is unfair, unjust and

discriminatory. It is arbitrary. Replete with biases, it

disproportionately affects the poorest and most vulnerable.

The death penalty has no place in our societies.

The welcome trend globally towards absolute abolition is

strong: 142 countries have now abolished the death penalty

in law or in practice. In 2017, four additional countries

abolished the death penalty or took steps towards doing so.

The evidence available, credible research, and testimonies

of those who have been on death row or fought for those on

death row have all played key roles in the success of the

global movement to eradicate death penalty.

With this publication, a major gap in our understanding of

the multiple harms and wrongs of death penalty has been

addressed.

As the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or

Arbitrary Executions, I am committed to adopting a gender

perspective to my mandate, by identifying and exposing the

many ways in which gender interacts with violations of the

right to life and revealing systemic discrimination that must

be remedied for all people to enjoy equal rights.

Until now women facing the death penalty have remained

largely invisible both in law and in the broader field. This

report is the first to examine when and how women receive

death sentences, and what happens to them once they reach

death row. I cannot emphasize enough the importance of

this kind of analysis in our campaigns against the death

penalty and systemic gender-based discrimination.

This report tells the stories of women sentenced to death by

courts that failed to consider their history as survivors of

gender-based violence and other forms of gender-based

oppression. As I have long advocated, when essential facts

of a capital defendant’s case, including domestic violence,

have been ignored, the imposition of the death penalty is

always arbitrary and unlawful. So is the death penalty

imposed as a result of proceedings in violation of the

principle of non-discrimination and fair trial. The report

shows that most women on death row come from

backgrounds of severe socio-economic deprivation and

many are illiterate, which has a devastating impact on their

ability to participate in their own defense and to obtain

effective legal representation.

Criminal justice processes, largely designed by and for

men, frequently are not only blind to the causes and

consequences of gender-based violence, they may actively

reinforce gender-based discrimination. Thus the report

reveals that courts judge women not just for their alleged

offenses, but also for what are perceived to be their moral

failings as women: as “disloyal” wives, “uncaring”

mothers, “ungrateful” daughters. Nowhere are

transgressions of the social norms of gender behavior

punished more severely than in a capital trial.

For all of these reasons, this long-overdue report is a most

welcome asset. It urges policy-makers, activists, scholars,

and lawyers to engage with the issue of gender

discrimination in application of capital punishment. It

demands that they incorporate an awareness of gender bias

into every aspect of their work, combat gender stereotypes

and overcome the binary view of women as either victims

or offenders. A human rights approach to capital

punishment cannot be complete without a gender

component, and what this report offers is the first body of

evidence to demonstrate it and thus to campaign effectively

and inclusively against death penalty.

This report also marks the launch of the Alice Project at the

Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide. By telling

the long-neglected stories of women on death row, the

Alice Project will shed light on how gender-based

discrimination plays out in countries that apply the death

penalty. It represents a first attempt to devote resources and

attention to the experiences of women on death row, to

develop human rights strategies around the application of

capital punishment to women, and to invite international

law to look to its own biases. I hope that this Project’s call

will be heard loudly, clearly and globally.

AGNÈS CALLAMARD

U.N. Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or

Arbitrary Executions

4

Executive Summary

We estimate that at least 500 women are currently on

death rows around the world. While exact figures are

impossible to obtain, we further estimate that over 100

women have been executed in the last ten years—and

potentially hundreds more. The number of women facing

execution is not dramatically different from the number of

juveniles currently on death row, but the latter have

received a great deal more attention from international

human rights bodies, national courts, scholars, and

advocates.

This report aims to shed light on this much-neglected

population. Few researchers have sought to obtain

information about the crimes for which women have been

sentenced to death, the circumstances of their lives before

their convictions, and the conditions under which they are

detained on death row. As a result, there is little empirical

data about women on death row, which impedes

advocates from understanding patterns in capital

sentencing and the operation of gender bias in the criminal

legal system. To the extent that scholars have focused on

women on death row, they have concluded that they are

beneficiaries of gender bias that operates in their favor.

While it is undeniable that women are protected from

execution under certain circumstances (particularly

mothers of infants and young children) and that women

sometimes benefit from more lenient sentencing, those

that are sentenced to death are subjected to multiple forms

of gender bias.

Most women have been sentenced to death for the crime

of murder, often in relation to the killing of family

members in a context of gender-based violence. Others

have been sentenced to death for drug offenses, terrorism,

adultery, witchcraft, and blasphemy, among other

offenses. Although they represent a tiny minority of all

prisoners sentenced to death, their cases are emblematic of

systemic failings in the application of capital punishment.

Women in conflict with the law are particularly

vulnerable to abuse and other rights violations, either at

the police station, during trial, or while incarcerated.

Women are more likely than men to be illiterate, which

affects their ability to understand and participate in their

own defense. For example, of the 12 women on India’s

death row in 2015, six have never attended school.

Illiteracy also increases their vulnerability to coercion,

heightening the risk of false confessions. In certain

countries, particularly in the Gulf states, most death-

sentenced women are foreign migrant workers who are

subject to discriminatory treatment.

Mental illness and intellectual disability are common

among women facing the death penalty. In Pakistan,

Kanizan Bibi has been on death row since 1989, when she

was only 16-years-old. Diagnosed with paranoid

schizophrenia, she cannot care for herself in the most

basic ways and has lost all awareness of her surroundings.

Although she is now confined in a psychiatric hospital,

she remains under sentence of death.

Many women enter prison as long-term survivors of

gender-based violence and harsh socio-economic

deprivation. We have documented several cases of women

convicted of crimes committed while they were minors,

often in the context of child marriage. These factors

receive little attention from lawyers and courts. In many

death penalty jurisdictions, gender-based violence is not

considered at sentencing. Few lawyers present such

evidence, and even where they do, the courts often

discount it. In mandatory death penalty jurisdictions, a

woman’s prior history as a survivor of physical or sexual

abuse is simply irrelevant, since the death penalty is

automatically imposed for death-eligible offenses without

consideration of the offender’s background or the

circumstances of the crime.

Our research also indicates that women who are seen as

violating entrenched norms of gender behavior are more

likely to receive the death penalty. In several cases

documented in this report, women facing the death

penalty have been cast as the “femme fatale,” the “child

murderer,” or the “witch.” The case of Brenda Andrew in

the United States is illustrative. In her capital trial, the

prosecution aired details of her sexual history under the

guise of establishing her motive to kill her husband. The

jury was allowed to hear about Brenda’s alleged extra-

marital affairs from years before the murder, as well as

details about outfits she wore. The trial court also

permitted the prosecutor to show the underwear found in

the suitcase in her possession after she fled to Mexico,

because it showed that she was not behaving as “a

grieving widow, but as a free fugitive living large on a

Mexico beach.” As one Justice of the Court of Criminal

Appeals of Oklahoma noted, Brenda was put on trial not

only for the murder of her husband but for being “a bad

wife, a bad mother, and a bad woman.”

5

Death row conditions around the world are harsh and at

times life-threatening for both men and women. In China,

for example, all death row inmates, including women, are

shackled at all times by their hands and feet. Women face

certain deprivations, however, that do not affect the male

population to the same extent. Some death sentenced

women must also care for infants or young children who

are incarcerated alongside them. Meriam Ibrahim,

sentenced to death in Sudan for apostasy in 2014, was

shackled to heavy chains in prison while eight months

pregnant and caring for a young child. In Thailand and

Myanmar, inmates have reportedly given birth alone in

prison. In many countries, it is challenging or impossible

for women to access sanitary pads or other menstruation

products. In Zambia, for example, women must make do

with rags that they struggle to clean without soap.

The social stigma associated with women who are

convicted and imprisoned, paired in some cases with

restrictive family and child visitation rules, means that

many female death row inmates around the world suffer

an enduring lack of family contact, contributing to the

high levels of depression suffered by women prisoners.

Women on death row may also be denied access to

occupational training and educational programs. For

instance, the general female prison population in Thailand

has access to work programs, but death row inmates do

not. One woman in Ghana explained, after being denied

educational opportunities while on death row: “I don’t do

anything. I sweep and I wait.”

Our country profiles aim to provide a snapshot of women

facing the death penalty in several major regions of the

world. The stories of women on death row provide

anecdotal evidence of the particular forms of oppression

and inhumane treatment documented in this report. It is

our hope that this initial publication, the first of its kind,

will inspire the international community to pay greater

attention to the troubling plight of women on death row

worldwide.

6

I. Introduction: Women on

Death Row, Invisible Subjects

of Gender Discrimination

When we began this research, we were surprised by the

dearth of information available about female death row

populations around the world. Although a number of

scholars have examined the causes, conditions, and

consequences of women’s incarceration more broadly,

few have focused specifically on women who have been

condemned to death.

1

As a result, there is little empirical

data about the crimes for which women have been

sentenced to death, the circumstances of their lives before

their convictions, and the conditions under which they are

detained on death row. This lack of research interest, we

believe, is in part attributable to the relatively small

numbers of women on death row. We were nonetheless

convinced, based on our own preliminary research, that

the cases of women condemned to death would reveal

significant patterns of arbitrariness and discrimination in

the application of the death penalty. Our research has

implications beyond the small population of women

facing death row. The factors we identify as affecting why

and how women are sentenced to death are relevant to all

women in conflict with the law. We hope that this report

illuminates how gender and poverty operate

intersectionally to create uniquely precarious conditions

for women facing capital sentences specifically, and

female defendants more broadly.

Faced with the absence of comparative research on this

topic, we spent three years assembling case studies and

reviewing anecdotal information from human rights

reports. We interviewed dozens of lawyers, activists, and

researchers who had first-hand knowledge of cases

involving women who had been condemned to death.

Based on our research, we can confirm that gender-based

discrimination is pervasive in all capital punishment

systems that we studied.

We define gender-based discrimination as the unequal or

unfair treatment of an individual on the basis of gender.

Gender-based discrimination affects all aspects of social

life, and our research has confirmed that capital trials

aggravate pre-existing gender-based inequality. At the

same time, it has revealed that gender-based

discrimination in capital trials is a complex issue because

there is often more than one form of bias at play, and

these biases may work both to the benefit and the

detriment of female capital defendants. The root of these

contradictions is the tendency of actors in the criminal

justice system to see women as victims and survivors

rather than as perpetrators of crime. The stereotype of

women as peaceful caregivers has benefitted many

women who have received reduced sentences as a result.

At the same time, women who are seen as violating

entrenched norms of gender behavior may be sentenced

more harshly. Women tend to receive lesser sentences

than men when perceived as victims that conform with

their assigned roles in society—the “caring mother,” the

“naïve girl,” or the “hysterical woman.” In contrast,

women tend to receive harsher sentences when perceived

as deviating from those roles—the “femme fatale,” the

“child murderer,” or the “witch.”

2

Women tend to receive lesser sentences

than men when perceived as victims that

conform with their assigned roles in

society—the “caring mother,” the “naïve

girl,” or the “hysterical woman.” In

contrast, women tend to receive harsher

sentences when perceived as deviating

from those roles—the “femme fatale,” the

“child murderer,” or the “witch.”

Domestic legal prohibitions on executing women reflect

this victim/offender binary. This is particularly true of

countries that have outlawed the execution of all women

on the basis of their gender alone. Currently, three

countries that retain the death penalty in their legislation

prohibit its application to all women, regardless of family

status, age, or offense: Belarus, Tajikistan, and

Zimbabwe. Discerning the rationale for the exclusion of

women in these three countries is a matter of some

conjecture, as there was little, if any, public debate

surrounding the introduction of these prohibitions. When

Belarus’s new criminal code of 1999, the first since

independence, excluded all women from the death

penalty, there was “no real debate” on the issue. The

provision seems above all to have codified an existing

practice: only three women are known to have been

executed in Belarus since 1953.

3

In Tajikistan and Zimbabwe, domestic law originally

prohibited the execution only of pregnant women (an

exclusion required by international law). The extension of

7

the ban to all women was a strategy for incrementally

reducing the use of capital punishment, rather than the

result of a gendered analysis. In Zimbabwe, the 2013

constitution banned the execution of women because the

drafters did not think that full abolition was politically

tenable. Excluding women was an achievable objective

because few women are executed and executing women

makes the public uncomfortable. It was also a potential

Trojan horse for abolition in light of the constitution’s

equality provisions. Indeed, a constitutional challenge to

the death penalty on equality grounds is currently

underway.

4

In Tajikistan, as in Mongolia, which excluded

women from execution until it abolished the death penalty

in 2015, the exemption for women “did not entail any

kind of discrimination on the grounds of sex; it existed

because…it was considered…a significant step towards

its complete abolition.”

5

Other legal prohibitions on executing women emphasize

the social importance of their roles as mothers. Pregnant

women are universally excluded from the use of the death

penalty, although in some countries they may be executed

after giving birth.

6

Altogether, at least fifty countries have

adopted legislation prohibiting the execution of mothers

with young children or are party to at least one

international treaty that prohibits the practice.

7

Article

4(2)(g) of the Protocol on the Rights of Women to the

African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights provides

that nursing mothers may not be executed, but refrains

from specifying an age at which a child is presumed to be

weaned. The Arab Charter on Human Rights prohibits the

imposition of the death penalty on a nursing mother

within two years from the date on which she gave birth.

These provisions fail to protect new mothers who cannot

or choose not to nurse their babies.

Limitations on executing pregnant women, or women

with young children, embody important human rights

norms, including the fundamental principle of prioritizing

the best interests of the child, and the authors of this

report fully support them. Nevertheless, it is worth

reflecting on the fact that these norms also signal that the

quality for which women deserve clemency is their

connection to motherhood. Such reasoning leaves women

who do not conform to this role—women who have no

children, and especially women whose offenses result in

harm to children—with default narratives of deviance and

place them at a heightened disadvantage in capital trials.

Women who are eligible for the death penalty under

domestic and international law face gender bias at

multiple levels. Our research has revealed a number of

cases of women whose capital trials were permeated with

candidly sexist language. In India, for instance, a woman

accused with her lover of killing her husband was

characterized by the court as the “kind of woman” who

brings “shame” upon her family, village, and society and

who represents a threat to women and men alike.

Referring to the woman’s extramarital affair, the court

commented that “a lady of such character deserves no

leniency.”

8

A Pakistani court, in refusing a woman’s bail

application in a drug smuggling case, observed: “Had the

accused been concerned about her suckling baby, she

would not have resorted to indulge in such activity which

had afflicted the whole society and especially the younger

generation.”

9

In a case involving a woman convicted of

killing several members of her family, the Supreme Court

of India stated that as a daughter, she had violated her

gender role as “the caregiver” for her parents.

10

The Court

further observed, “[the daughter] is a caregiver and a

supporter, a gentle hand and a responsible voice, an

embodiment of cherished values of our society and in

whom a parent places blind faith and trust.”

11

In all of

these cases, courts chose to arrange the evidence before

them in the shape of familiar narratives about women,

rather than grapple with the complexities of a human

being who happened to be a woman.

In India, for instance, a woman accused

with her lover of killing her husband was

characterized by the court as the “kind of

woman” who brings “shame” upon her

family, village, and society and who

represents a threat to women and men

alike.

In other cases, the evidence of gender bias is more subtle,

but nonetheless unmistakable. One lawyer in Iran noted

that courts trying women capital defendants judge their

whole lives, and not just the offense with which they are

charged (particularly in cases where the defendant is

accused of killing her spouse).

12

At the investigation stage, police officers’ gender biases

and stereotypical assumptions about femininity influence

their behavior and decision-making regarding female

offenders. For instance, Pakistani police officers

8

reflexively target wives as the prime suspects in their

husbands’ murders if no other suspect is immediately

apparent.

13

Our research has also revealed the tendency to

arrest women along with their husbands or other male

figures in their lives. In India, at least nine out of 12

women on death row were charged with one male co-

defendant and at least 6 of these men were their intimate

partners.

14

In a minority of death row cases in India a

woman was the sole accused.

15

Moreover, in one instance,

the female death row prisoner reported that her trial

lawyer would only meet with her husband regarding their

case, and then her husband would explain to her the case

details.

16

Seven out of nine cases of women on death row

in Indonesia also involved male co-defendants, usually an

intimate partner.

17

Little attention has been devoted to the

question of whether some of these women may face a

capital sentence because of their association with their

male co-defendants, potentially jeopardizing their

presumption of innocence and entitlement to an

individualized judicial process.

Biased treatment by law enforcement exacerbates the pre-

existing vulnerabilities of many female offenders,

especially those from rural areas. Lack of education

prevents many women from being able to read and

interpret legal documents, or to be fully engaged in their

own defense.

18

Additionally, women frequently lack

money or property of their own, which impedes their

ability to retain qualified legal counsel. Lack of economic

resources also makes it practically impossible for many

women to compensate the victim’s family in legal systems

where financial restitution can lead to a reduction in their

sentence.

19

At sentencing, gender bias exists not simply when

gendered stereotypes are mobilized to establish

culpability, but also when gender is simply ignored in the

courtroom. Women defendants suffer from harsher

sentences when there is no recognition of how gender and

patriarchy affected their criminal conduct. Fundamental

concepts in criminal law, such as intent and volition, often

take for granted the actor’s agency in determining their

conduct. But survivors of domestic violence, for example,

do not enjoy such agency. Trauma and the threat of

violence influence the defendant’s ability to escape the

peril in which they find themselves.

One of the most striking instances of gender bias at

sentencing affects female defendants who are survivors of

domestic abuse. In mandatory death penalty jurisdictions,

such as Tanzania, gender-based violence is only relevant

where the defendant can proffer a self-defense claim. The

legal doctrine of self-defense, however, is limited to lethal

force deemed “reasonable” and “necessary” to protect life

or limb from imminent threat.

20

A woman who kills her

batterer while he is asleep, for example, even after a

lifetime of domestic violence, would not necessarily be

able to invoke this doctrine.

21

One of the most striking instances of

gender bias at sentencing affects female

defendants who are survivors of domestic

abuse.

Even in countries where judges exercise discretion in

applying the death penalty, courts do not consistently take

note of abuse, gender-based violence, and trauma when

making decisions about the appropriate sentence. As an

initial matter, lawyers in most countries lack the resources

and training to document and explain gender-based

violence to the court.

22

But even where advocates are able

to gather such evidence to present to the court at

sentencing, courts may disregard it.

23

In capital trials, it is often men who tell the stories of

women facing the death penalty. In most retentionist

countries, women are poorly represented in the ranks of

police officers, lawyers, and judges. The absence of

women making key decisions over the course of criminal

prosecutions may be another contributing factor for the

justice system’s failure to take into account women’s

experiences. The legal system is imbued with patriarchal

norms, and our research indicates that this inherent bias

has contributed to the wrongful convictions and death

sentences of women throughout the world.

9

II. Methodology

This project relied heavily upon partnerships with country

experts, including practicing capital defense lawyers as

well as activists, academics, and organizations working on

issues related to the death penalty, women’s rights, and

women’s imprisonment. These partners draw their

knowledge from their work with a wide range of

stakeholders in the criminal justice system, including

defense lawyers, civil society, prison administrators, and

prisoners under sentence of death.

The researchers conducted extensive desk research on the

myriad issues facing women on death row around the

world, including by collecting general and country-

specific reports, journal articles, statistical data, reports to

international human rights bodies, case files, country-

specific legislation and jurisprudence, and newspaper

reports.

Further, researchers conducted interviews with country

experts from Cameroon, China, India, Iran, Japan, Jordan,

Malawi, Mauritania, Morocco, Nigeria, Pakistan,

Thailand, United Arab Emirates, Uganda, Zambia, and

Zimbabwe.

The Center partnered with experts/organizations in

Indonesia, India, Jordan, and Pakistan, who conducted in-

depth country investigations and produced detailed reports

based on their research.

Where possible, this report drew upon information

specific to women on death row. Where such information

was not available, the report relies on information about

women prisoners and defendants more broadly. As a last

resort, the report refers to the experiences and conditions

of death row prisoners, who are mostly male. We have

indicated in the text that follows when we rely on

information regarding defendants or prisoners who are not

women on death row.

III. Women Facing the Death

Penalty around the World: An

Understudied Population

Gender discrimination in capital criminal proceedings is

an understudied phenomenon, in part because there are

relatively few women on death row. Although exact

figures are difficult to find and, in some countries,

impossible to obtain, our research suggests that women

represent less than 5% of the world’s death row

population and less than 5% of the world’s executions.

Nonetheless, we estimate that at least 500 women are

currently on death rows around the world.

A. SENTENCES

In Asia, where most of the world’s executions are carried

out, women make up a small fraction of those on death

row. For instance, women represent 5.7% of death row

prisoners in Japan (eight women),

24

and 2.3% in Taiwan

(one woman).

25

Estimates of the percentage of women on

death row in China range from 1% to 5%. Given the size

of China’s death row population, these figures represent

dozens, if not hundreds of women.

26

Women make up 3%

of all death row prisoners in India (12 women),

27

and

2.5% in Bangladesh (37 women).

28

As of 2017, there were

33 women on death row in Pakistan

29

out of around 5,000

prisoners for whom data is available,

30

or roughly 0.6%.

There were nine women on death row in Indonesia whose

sentences had been finalized as of September 2017, or

about 6% of all death row prisoners with finalized

sentences.

31

By contrast, women make up 18% of the

death row population in Thailand (94 women).

32

The proportion of death-sentenced women is even smaller

in largely de facto abolitionist Africa. Female inmates

represent approximately 15% of the death row in Malawi

(four women),

33

4% in Uganda (11 women),

34

2.2% in

Nigeria (32 women),

35

3.1% in Ghana (five women),

36

1.8% in Mauritania (one woman),

37

and 1% in Zambia

(two women).

38

In 2016, Kenyan President Uhuru

Kenyatta commuted the sentences of all prisoners on

death row—2,655 men and 92 women—into life

sentences.

39

Since then, more people have been sentenced

to death in Kenya but it is unclear how many of these are

women.

40

10

The proportion of women on death row is more variable

in the Middle East, the region with the world’s highest

per capita execution rate. As of August 2014, there were

25 women on death row in Iraq out of 1,724 death-

sentenced prisoners, or about 1.4%.

41

In recent years,

however, the death sentence has been applied to women in

Iraq with alarming frequency for alleged ties to the so-

called “Islamic State” or ISIS.

42

Currently, 560 women

are awaiting trial in detention on charges of aiding or

being members of ISIS.

43

In the United Arab Emirates, as of June 2018 there were

nine women under sentence of death out of around 200

death row inmates.

44

All but one were foreign nationals,

45

and most of these (if not all) were migrant workers.

46

In

Jordan, there are 16 women on death row out of 120 death

row inmates (13%).

47

The number of death-sentenced

women in Saudi Arabia is unknown. Nevertheless, Saudi

Arabia has executed at least nine women out of the

hundreds of prisoners it has put to death since 2015.

48

Iranian human rights lawyers estimate that there are

dozens of women on death row in Iran and in 2017, at

least ten women were executed.

49

In the Americas, the only state that has carried out

executions in the past few years is the United States,

where there were 54 women on death row as of October

2017, representing 1.93% of the total death row

population.

50

Since 1973, 181 women have been

sentenced to death in the United States, which constitutes

about 2% of all death sentences there.

51

There are very

few women on death row in the Caribbean.

B. EXECUTIONS

Women are also executed in significantly smaller numbers

than men. Some retentionist death penalty states have

executed few or no women in their history. India, for

instance, has not executed a woman in recent times.

52

Thailand has executed three women since 1942.

53

The countries that execute the greatest number of women

are the world’s two leading executioners: China, which in

recent years has executed an estimated 20 to 100 women a

year (1% to 5% of its total executions), and Iran, which

has executed at least 38 women in the past three years

(1.8% of its executions, on average).

54

The next three

states with the highest number of executions have

executed less than five women a year in the last few years.

Iraq executed 17 women between 2004 and 2014, around

2.5% of its total executions.

55

Saudi Arabia has executed

less than five women a year in the past five years,

representing around 2.2% of its executions. In the United

States, 16 women have been executed since the death

penalty was reinstated by the Supreme Court in 1976.

This represents about 1% of its total number of

executions. The United States executed two women in

2014 and one in 2015.

56

Women have also been executed in recent years in

Egypt,

57

Kuwait,

58

Jordan,

59

North Korea,

60

Afghanistan,

61

Indonesia,

62

Gambia,

63

and Somalia.

64

11

IV. Crimes for Which Women

Are Sentenced to Death

Although women are sentenced to death and executed at

lower rates than men overall, they are sentenced to death

at higher rates for certain categories of crimes, such as

sorcery and adultery.

65

In addition, the facts of the crimes

for which women are condemned to death reveal patterns

linked to gender.

A. WOMEN ON DEATH ROW FOR MURDER

Available data indicates that most women on death row

have been sentenced to death for the crime of murder.

Many of these crimes involve murders of close family

members in a context of gender-based violence. In China,

which executes the most women in the world, one expert

estimated that a significant number, possibly up to half, of

the women sentenced to death for murder had killed

family members.

66

Yemen’s Interior Ministry reported

that of the 50 women arrested for killing their husbands in

2012, most of them had been motivated by domestic

violence and gender inequality.

67

While we do not know

how many of these women were eventually sentenced to

death, murder in Yemen carries the mandatory death

penalty unless the victim’s family pardons the offender.

We found reports of women sentenced to

death for killing their abusers in Taiwan,

Uganda, Morocco, Jordan, Malawi, Nigeria,

and China.

Of the 16 women who were on death row in India as of

September 2017, six were sentenced to death for the

murder of their immediate or extended family.

68

In two

cases, the women’s families had opposed romantic

relationships with men they judged unsuitable.

69

A third

woman was sentenced to death for killing her husband;

her lover, who was also charged in the crime, received a

life sentence.

70

In Iran, information gathered from the Iran Human Rights

Documentation Center indicates that most women on

death row were sentenced to death for the murder of their

abusive husbands.

71

In many cases, these women were

married at a young age, without the right to divorce their

assailants.

72

We found reports of women sentenced to

death for killing their abusers in Taiwan,

73

Uganda,

74

Morocco,

75

Jordan,

76

Malawi,

77

Nigeria,

78

and China.

79

The phenomenon is both widespread and under-

investigated, and merits more in-depth research.

There are striking similarities among women sentenced to

death for killing abusive family members. Most cases

involve long-term abuse and the absence of effective

outside help. Economic dependence, fear of losing child

custody, widespread societal tolerance of violence against

women, and the difficulty and stigma involved in

obtaining a divorce exacerbate the effects of marital

abuse. Several death-sentenced women in this category,

particularly in Iran and Nigeria, had been forcibly married

at a young age. In Sudan, for example, 19-year-old Noura

Hussein was reportedly sentenced to death for murdering

her husband after he raped her. Noura’s family compelled

her to marry at 15, but she refused and escaped for three

years. Her father forced her to return and complete the

wedding ceremony in April 2017. Noura’s husband raped

her after she refused to have sex with him. The following

day, Noura stabbed and killed her husband as he tried to

rape her again.

80

Women facing capital prosecution arising out of domestic

abuse suffer from gender discrimination on multiple

levels. To begin with, evidence of abuse is difficult to

gather. Most domestic violence occurs without any adult

witnesses, and female defendants may be reluctant to

speak out due to stigma, shame, and lack of trust in police

and judicial proceedings. Even if evidence of domestic

violence is presented to the court, women face substantial

barriers in convincing a court that they acted in self-

defense. In many countries, to meet the legal definition of

“self-defense,” a defendant must show that she reasonably

perceived an imminent risk of bodily harm or death, or

that she acted to repel an ongoing attack. This definition

fails to recognize the dynamics of domestic abuse, which

is often perpetrated continually over a long period of time.

A woman who has been repeatedly abused may

reasonably perceive danger to her life that may not be

immediate but is nonetheless ever-present.

81

Courts,

however, are generally disinclined to believe that a

woman would remain in a long-term relationship if she

believed herself to be in serious danger. They may also

conclude that the defendant overreacted to a situation that

did not create an imminent risk of harm or death. In the

United States, “stand your ground” laws,

82

which provide

immunity and defense to criminal prosecution, have been

rejected by some courts when survivors of domestic

12

violence have invoked them to justify their use of force

when defending themselves from long-time abusers.

83

As the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human

Rights has observed, it is “extremely rare” for domestic

abuse to be treated as a mitigating factor during

sentencing, although it is known to produce serious

physical harm, mental trauma, depression, and

psychological distress.

84

In countries with a mandatory

death penalty, there is simply no mechanism that would

allow the courts to consider such evidence. Thus, in the

case of Alice Nungu, who killed her husband after he

came home drunk and began to beat her, the Malawi High

Court was unable to take into account her history as a

victim of domestic violence.

85

Even in those countries

with discretionary capital sentencing, courts may ignore

or discount the significance of gender-based violence and

its consequences. Sometimes, courts within a same

country have divergent approaches to domestic violence,

leading to the arbitrary application of death sentences.

86

Li Yan killed her husband with the butt of a

rifle that he had brandished during a fight.

Throughout their marriage, he beat and

kicked her, put out cigarettes on her face,

and locked her in their home during the

day and out overnight.

Nevertheless, there are signs that some jurisdictions are

beginning to consider domestic violence in capital trials.

In 2014, a court in Belize applied the so-called “battered

women’s syndrome” doctrine for the first time in the

Caribbean, declining to apply the death penalty to Lavern

Longsworth after finding that she killed her husband after

years of physical and sexual abuse.

87

In June 2014,

China’s Supreme Court overturned the death sentence of

Li Yan, whose high-profile case had elicited widespread

public calls for leniency. Li Yan killed her husband with

the butt of a rifle that he had brandished during a fight.

Throughout their marriage, he beat and kicked her, put out

cigarettes on her face, and locked her in their home during

the day and out overnight.

88

China’s Supreme Court and

Procuratorate (the state’s prosecutorial body) have

recommended that courts no longer seek the death penalty

for defendants who kill abusive spouses. Similarly, in

August 2017, Indonesia’s Supreme Court enacted new

Guidelines on Sentencing Women who are in Conflict

with the Law (PERMA 3/2017) to ensure that women’s

rights are upheld during hearings, as well as to identify

discrimination and bias against women.

89

B. WOMEN ON DEATH ROW FOR DRUG OFFENSES

After murder, drug-related offenses are the most common

crimes that lead to death sentences for women—

particularly in the Middle East and Asia. For example, the

overwhelming majority of women on death row in

Thailand were convicted of drug-related offenses.

90

In

Iran, drug trafficking is the crime for which women are

most frequently sentenced to death, after murder.

91

At

least 43 women were hanged for drug crimes in Iran from

2001 to 2017.

92

For instance, Hourieh Sabahi, Leila

Hayati, and Roghieh Khalaji, single mothers from

economically deprived backgrounds who had no criminal

histories, were executed in 2001. Their lawyer argued that

their death sentences were illegal under Iranian law

because of the small quantity of narcotics involved.

93

Gender inequality also permeates prosecutions of women

for capital drug offenses. Gender dynamics and female

disempowerment are salient factors associated with

women’s involvement in drug smuggling.

94

Many women

engage in drug smuggling to counteract their

marginalization and improve their socioeconomic status.

95

In Iran, for example, most drug offenses involving women

are small-scale offenses committed by women from

economically deprived backgrounds.

96

Drug traffickers

employ women as low-level drug mules because they are

less likely to be caught than men and do not have the

resources to buy and traffic drugs for their own profit,

exposing them to exploitation by drug trafficking rings.

97

Researchers have concluded that some women smuggle

drugs to please or help someone, usually a male figure, in

their lives.

98

Other studies have found that women who

were victims of child and/or domestic abuse may engage

in drug smuggling to increase their self-esteem.

99

Many women engage in drug smuggling to

counteract their marginalization and

improve their socioeconomic status.

Female migrant workers are easy targets for drug

trafficking rings because they are typically poor and

uneducated, but hold passports.

100

For example, Mary

Jane Veloso, a Filipina mother of two boys and former

domestic worker in Dubai, was sentenced to death by

firing squad in Indonesia for drug smuggling, which

13

carries a mandatory death sentence. Mary Jane and her

legal team have consistently claimed that she had escaped

from Dubai after an attempted rape and that she was a

victim of human trafficking duped into smuggling heroin

into Indonesia.

101

Tran Thi Bich Hahn, a Vietnamese

national, was executed by firing squad in Indonesia in

2015 for drug smuggling. She claimed that she was duped

by a drug cartel to transport a suitcase from Malaysia—

containing 2.4 pounds of methamphetamine—into

Indonesia.

102

C. WOMEN ON DEATH ROW FOR OFFENSES

AGAINST SEXUAL MORALITY

One other category of capital offense deserves particular

attention. In some Shariah jurisdictions, offenses against

sexual morality, or zina, appear gender-neutral on their

face, but in practice are applied in a discriminatory

manner against women. Zina—illicit sexual relations

outside of marriage—is a capital offense for a married

person. Under Shariah principles, a zina conviction

implies a consensual sexual relationship and requires a

very high standard of proof: the testimony of four

eyewitnesses or a confession.

103

It follows that zina

convictions should be exceedingly rare. Pregnancy may

constitute prima facie evidence of illicit sexual relations,

but according to accepted Shariah rules, pregnancy is not

determinative because it may have resulted from rape.

104

Some modern Islamic criminal systems, however, fail to

apply these Shariah principles. In Iran, married rape

victims are at risk of execution for adultery because of

practices which defy these rules. These practices reverse

the high evidentiary burden, requiring that pregnant

women suspected of adultery prove, by four eyewitness

accounts, that their pregnancy resulted from rape—an

extraordinarily difficult burden to meet.

105

The risk of being prosecuted for zina creates a strong

disincentive for women to report rape or sexual assault. In

July 2013, a Norwegian woman on a business trip to

Dubai reported a rape to the police, only to be sentenced

to 16 months’ imprisonment for sex outside of marriage

and alcohol consumption.

106

Following intense diplomatic

pressure, she was eventually pardoned and released.

107

Similarly, women who have reported rape in Pakistan

have been charged with adultery.

108

Zafran Bibi, for

instance, was convicted of adultery and sentenced to death

by stoning after she declared that she was raped by her

brother-in-law. The judge considered her pregnancy proof

of adultery since Zafran’s husband was in jail at the time.

No charges were brought against the brother-in-law

because medical tests showed no signs of force and no

witnesses were available to corroborate Zafran’s

account.

109

The method of execution prescribed for zina—stoning—is

almost never applied in practice. Still, it is discriminatory

on its face. Shariah law dictates that if the prisoner

succeeds in freeing themselves during the stoning, he or

she will be pardoned. In preparation for stoning, men are

buried to their waist in the ground while women are tied

up and buried deeper (theoretically to prevent their breasts

from being stoned). Some men, but virtually no women,

are able to escape execution. In Sudan, Intisar Sharif

Abdallah, whose age was believed to be under 18, was

sentenced to death by stoning for adultery. The state failed

to provide Intisar with a lawyer or interpreter, even

though Arabic is not her first language; moreover, her age

was never assessed by the court.

110

Intisar was released in

July 2012 after the Ombada court in Omdurman dropped

all charges against her due to a lack of evidence.

111

The

vast majority of adultery cases and stoning sentences in

Sudan have been imposed on women, pointing to the

disproportionate and unequal application of this draconian

law.

112

Even where stoning sentences are eventually

modified, women must live with the terror of such a

sentence—a punishment which is in itself cruel and

inhumane.

Married sex workers and married victims of sex

trafficking also face capital punishment under these laws.

One Iranian case exemplifies the tragic and absurd

consequences of such a system: a woman forced by her

abusive husband into prostitution was convicted as an

accomplice to murder when one of her male clients killed

her husband. She was also sentenced to death by stoning

for adultery. The male client, in contrast, was sentenced to

a jail term of eight years.

113

D. WOMEN ON DEATH ROW FOR TERRORISM-

RELATED OFFENSES

Women also face capital punishment for terrorism-related

offenses, especially in Iraq, Pakistan,

114

India, and Iran. In

recent years, Iraqi courts have sentenced more than 3,000

people to death, including dozens of women,

115

many of

whom were convicted of crimes relating to membership in

ISIS. Iraqi and foreign women are receiving the harshest

sentences because they traveled to live under ISIS,

married an ISIS member, or received a stipend from ISIS

14

after the death of their husbands.

116

After spending weeks

in overcrowded and unsanitary detention centers, women

attend an abbreviated trial where their fates are decided.

Defense lawyers, when appointed, are unable to

communicate with their clients prior to trial, present any

evidence in court, summon any witnesses, or use qualified

translators. Most trials end with sentences of life in prison

or capital punishment.

117

In Yemen, 22-year-old Asmaa al-Omeissy was sentenced

to death in 2018 on “state security” charges in a rebel-

controlled area of Yemen.

118

While traveling to her

father’s home in the Houthi-controlled region of Sana’a,

Asmaa was detained by Huthi rebels.

119

While in

detention, Asmaa was tortured and accused of terrorism,

collusion with foreign powers, and illicit sexual

intercourse with her travel companions.

120

Following a

trial that lacked substantive procedural guarantees, she

was condemned to death while her father and two travel

companions were released.

121

In Iran, Shirin Alamhouli

was hanged in 2010 after being convicted of moharebeh

(enmity with God) for her alleged involvement in the Free

Life Party of Kurdistan (PJAK) group. A few days before

her impromptu execution, Shirin wrote in a letter: “I was

arrested in April 2008 and was taken directly to the

headquarters of the Sepah. As soon as we arrived there,

and before I was asked any questions, they began beating

me. I was there 25 days, of which I was on hunger strike

for 22 days. I suffered all types of physical and mental

torture.”

122

India also Fehimda Syed sentenced to death in

2009 for participation in the 2003 Mumbai bombings.

123

E. WOMEN ON DEATH ROW FOR WITCHCRAFT

Although men have been sentenced to death for

witchcraft, it is typically women who are accused of

sorcery-related crimes. The word “witch” is almost

exclusively used to refer to a woman. For centuries,

women have been persecuted, prosecuted, tortured, and

executed for witchcraft, which is perceived as the cause of

misfortunes including deaths, illnesses, accidents, loss of

livestock, and droughts.

124

The practice continues today.

In 2006, Fawza Falih was sentenced to

death in Saudi Arabia for “bewitching” a

man, causing him to become impotent.

According to the United Nations, thousands of women are

still hunted, beaten, tortured, and in many cases murdered

because of their reputed use of witchcraft.

125

Nevertheless,

death sentences and judicial executions for witchcraft are

becoming scarcer and are mainly applied in Saudi Arabia.

In 2006, Fawza Falih was sentenced to death in Saudi

Arabia for bewitching a man, causing him to become

impotent. The judges relied on Fawza’s coerced

confession and on the statements of witnesses who

claimed to have seen her bewitching the man. In court,

she explained that her interrogators beat her during 35

days in detention at the hands of the religious police, and

that as an illiterate woman, she did not understand the

document she was forced to fingerprint.

126

Likewise,

Amina bint Abdel Halim Nassar was reportedly beheaded

in Saudi Arabia for practicing witchcraft in 2011.

127

F. WOMEN ON DEATH ROW FOR OTHER OFFENSES

In Iran, 17-year-old Leyla Mafi was

arrested during a raid on a brothel and

sentenced to death for prostitution.

Prostitution, brothel keeping, blasphemy, kidnapping, and

armed robbery are other crimes for which women receive

capital punishment. In Iran, 17-year-old Leyla Mafi was

arrested during a raid on a brothel and sentenced to death

for prostitution. Leyla, who was forced into prostitution

by her mother when she was eight, was intellectually

disabled. Leyla’s death sentence was eventually

commuted. Instead, she received 99 lashes and was sent to

a rehabilitation center in Tehran in 2006.

128

In Nigeria,

armed robbery is the crime for which women are most

frequently sentenced to death, after murder.

129

In China,

women have been sentenced to death for financial crimes

and child trafficking.

130

Women in Sudan and Pakistan

have been sentenced to death for apostasy

131

and

blasphemy

132

.

In 2010, Aasia Bibi, an illiterate farmer and mother of

five, was sentenced to death by hanging for blasphemy in

Pakistan. One day while working in the fields, a group of

Muslim women refused to drink water from a water bowl

arguing that Aasia, who is Christian, had contaminated it.

15

Aasia Bibi

During the incident, the women accused Aasia of

blasphemy, a charge that she denied.

133

Aasia has been on

death row for eight years and is currently waiting for the

Supreme Court to hear her appeal.

134

V. Women in Vulnerable

Situations Facing the Death

Penalty

The death penalty is often applied to the most vulnerable

and marginalized members of society. The vast majority

of death row prisoners are indigent, and many suffer from

mental disorders or intellectual disabilities. In some

countries, members of racial, ethnic, or religious

minorities are especially vulnerable to prosecution for

capital crimes.

Women on death row are no exception. But women also

face intersecting forms of discrimination based on “gender

stereotypes, stigma, harmful and patriarchal cultural

norms and gender-based violence,” all of which have “an

adverse impact on the ability of women to gain access to

justice on an equal basis with men.”

135

Youth, forced

and/or child marriage, mental illness or intellectual

disability, migrant worker status, poverty, and race and

ethnicity are all factors that increase the risk that a woman

will be sentenced to death. Many women on death row fall

into several of these categories, compounding their

vulnerability.

A. JUVENILES AND SURVIVORS OF FORCED

MARRIAGE

One of the most widely accepted tenets of international

law prohibits the imposition of death sentences on

children under the age of 18 at the time of the offense.

136

Nevertheless, some countries continue to execute

juveniles, in part because of the legal system’s failure to

verify an offender’s age at the time of the offense.

137

While a minority of women on death row are juvenile

offenders, their cases merit close scrutiny because of their

vulnerability and because the patterns their cases reveal

are emblematic of the challenges faced by many women

on death row.

Virtually all cases of death-sentenced minors that we

found involve gender-based violence, child marriage,

and/or sexual abuse. Trial courts around the world largely

fail to take into account gender-based violence as a

mitigating factor to reduce sentences, even in the context

of child marriage.

138

This omission erases the role of

domestic violence in cases of female minors who kill their

abusers, a significant concern given the prevalence of

16

domestic abuse worldwide in marriages involving girls.

139

Similarly, courts rarely consider the mental health effects

of child marriage, such as post-traumatic stress disorder,

depression, and other mental or emotional disorders.

140

While youthfulness exacerbates these effects, adult

women in abusive relationships should also benefit from

the protection of laws recognizing the relevance of

domestic abuse and child marriage to capital sentencing.

Virtually all cases of death-sentenced

minors that we found involve gender-

based violence, child marriage, and/or

sexual abuse.

Four cases from four different countries illustrate the

universality of these concerns across cultures and legal

systems. The recent case of Maimuna Abdulmumini in

Nigeria is emblematic. Maimuna was married at the age

of 13. Five months into her marriage, her husband burned

to death in alleged arson attack while he slept. Maimuna

was arrested and charged with murder. She languished in

prison for six years while her trial dragged on. In 2012, a

Nigerian court convicted Maimuna of culpable homicide

and sentenced her to death. Lawyers acting pro bono

challenged her death sentence before a regional court, the

ECOWAS Community Court of Justice, arguing that

imposing a death sentence on a juvenile violated

international law and the African Charter on the Rights

and Welfare of the Child. The ECOWAS court ruled that

Nigeria had violated its international human rights

obligations, ordered a stay of execution, and awarded

Maimuna damages.

141

Maimuna was released from prison

in 2016.

142

The case of Zarbibi,

143

sentenced to death in Iran, raises

similar concerns. Zarbibi was 15 years old when she was

forced to marry a 27-year-old man. In a diary she wrote

from her prison cell, she described how her husband

abused her physically and sexually, separated her from her

family, and forced her to leave school. At the age of 16,

while four months pregnant, she killed her husband with a

kitchen knife.

144

The court sentenced her to death, and she

gave birth to her daughter while imprisoned on death row.

Under Shariah law, the family of the victim may pardon

the perpetrator of a serious crime. Zarbibi’s late husband’s

family pardoned her on the condition that she marry his

brother.

145

She agreed and was released from death row.

According to her lawyer, however, her freedom remains

highly restricted.

146

In Tanzania, Mary Raziki,

147

who was forced to marry at

age 16, was sentenced to death for the murder of her co-

wife. Mary suffered severe domestic violence at the hands

of her husband, including physical, psychological, and

economic abuse. According to Mary’s older sister, Mary’s

house resembled a cow shed. Mary’s husband stole crops

from Mary’s shamba (farm) to take them to his new

home, forcing Mary to work several jobs, and sometimes

beg for money to feed their children.

148

Mary sought

protection from village authorities and from her family,

but they did nothing to prevent the violence, protect Mary

and her children, or hold her abusive husband

accountable. Mary stated that she did not intend to cause

the death of her husband’s second wife; she set fire to

their home believing it was empty. Because of Tanzania’s

mandatory death penalty scheme, however, the trial judge

was unable to consider her lack of malice or the abuse she

suffered, and sentenced her to death. Mary has been on

death row for more than 15 years.

149

In Indonesia, although juveniles are by law excluded from

capital punishment, some courts have treated girls under

the age of 18 as criminally responsible adults by virtue of

their married status, even when they act under compulsion

from their adult husbands. One woman currently on death

row was a minor but married at the time of her offense.

Susi

150

was convicted of killing a child when she was 17

years old under the orders of her older, abusive husband.

Her husband had previously and without her knowledge

killed six boys and one man. The court acknowledged in

its findings of fact that Susi was not aware of her

husband’s homicidal acts. Importantly, the court further

acknowledged that she repeatedly resisted her husband’s

orders to kill a child and only obeyed after he threatened

her life. Despite these findings, Susi and her husband

received the same sentence: a death sentence for

premeditated murder. The maximum punishment for a

juvenile offender is normally 10 years’ imprisonment but

this girl was sentenced to death.

151

B. WOMEN WITH MENTAL ILLNESSES AND

INTELLECTUAL DISABILITIES

Multiple studies have confirmed that incarcerated women

suffer high rates of mental illness. According to a study

carried out in the United States from 2011 to 2012,

incarcerated women reported significantly higher rates of

mental health problems than men in prison.

152

In the

United Kingdom, women in prison are five times more

likely to have a mental health issue than women in

17

general. Close to half of incarcerated women in the U.K.

report having attempted suicide, which is twice the rate of

men in prison (21%).

153

The World Health Organization

found that incarcerated women have high rates of

substance abuse and histories of abuse.

154

International law prohibits the execution of individuals

with mental illness or intellectual disability.

155

The U.N.

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights has

urged all retentionist states not to impose the death

penalty on or execute a person suffering from any mental

or intellectual disabilities.

156

While there is widespread

agreement on the prohibition, in practice states do not

apply it.

The case of Grace Banda

157

is illustrative. Grace, an

intellectually disabled grandmother, was sentenced to

death in Malawi in 2003.

Grace Banda. Photo by Sofia Moro.

Dr. George Woods, a neuropsychiatrist, concluded that

she suffers from intellectual disability as well as Fetal

Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). She attended three

years of primary school but she cannot read or write. As a

child her growth was stunted, most likely as a result of

FASD and malnutrition. Grace had been married for over

30 years, then left her husband after he started beating her

and having relations with other women. During a famine

in her village, her grandsons stole maize from a

neighbor’s field. One of the boys, suffering from

malnutrition, died from the beating she inflicted to

discipline him. She attempted to revive him to no avail,

and later reported the incident to the authorities. After

spending 13 years on death row, Grace was granted a

sentence rehearing in 2016.

158

Based in part on her