Testing Swensen

Measuring the Value Added by Alternative Assets

within the Investment Pools of Non-profit Organizations

Jon M. Luskin

A thesis submitted

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree

Master of Business Administration

American Jewish University

2013

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 2

Signature Page

The thesis of Jon M. Luskin is approved.

__________________________________ ____________

Larry Weinman, MBA date

__________________________________ ____________

Seth Weintraub, MBA, CMA date

__________________________________ ____________

Gerald J. Wacker, Ph.D. date

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 3

Dedication

To my family, for their support

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 4

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements ..............................................................................................................6

Abstract ................................................................................................................................7

Chapter 1: Introduction ........................................................................................................8

Scope ........................................................................................................................8

Orientation ...............................................................................................................8

Personal Background .............................................................................................10

Conceptual Framework ..........................................................................................10

Chapter 2: Literature Review .............................................................................................19

Overview ................................................................................................................19

Summary of Major Sources ...................................................................................19

Methodology ..........................................................................................................20

Overall Summary and Comparison ........................................................................20

Critique ..................................................................................................................21

Point of Departure ..................................................................................................22

Chapter 3: Empirical Study Method ..................................................................................23

Hypotheses .............................................................................................................23

Background of the Data Source .............................................................................24

Procedure Used to Collect Data .............................................................................24

Advantages and Disadvantages of this Method .....................................................24

Chapter 4: Findings ............................................................................................................26

California Social Services Organization ................................................................27

University of Hawaii Foundation...........................................................................30

Washington State University Foundation’s Endowment Fund ..............................33

University of Northern Carolina, Wilmington .......................................................35

University of California, Santa Barbara Foundation .............................................37

University of California, Irvine Foundation ..........................................................39

University of California, Riverside Foundation.....................................................41

University of California, San Francisco Foundation .............................................43

Chapter 5: Conclusions ......................................................................................................45

Theoretical Insights ................................................................................................45

Practical Recommendations ...................................................................................47

What this Study Adds to the Literature ..................................................................51

Suggestions for Future Research ...........................................................................51

Works Cited ...........................................................................................................52

Appendices .........................................................................................................................57

Appendix A: Indexing vs. Active Management ....................................................58

Appendix B: Risk-Free Rate ..................................................................................62

Appendix C: Basic Investing Principles Glossary .................................................63

Appendix D: 60/40 Benchmark .............................................................................66

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 5

Appendix E: Digest of the Literature .....................................................................67

Appendix F: CSSO Net of Fees Estimate ..............................................................99

Appendix G: CSSO’s Problematic Portfolio .......................................................101

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 6

Acknowledgements

This work would not have been possible without the contribution of many individuals.

My father helped me clarify some of the more complex points for lay readers. My fiancé

took the time to edit the document, even though she was busy studying for her CPA

exams. My thesis advisor, Dr. Gerry Wacker, graciously took the time to meet with me

on many occasions. Seth Weintraub, a thesis reader, taught a stimulating course at

American Jewish University that further ignited my interest in finance. Larry Weinman,

another thesis reader, helped by explaining various investment principles and enlightened

me on the easiest way to calculate investment returns. Steven Vielhaber not only

discussed my findings with me, but also introduced me to Regina Fales, who introduced

me to David F. Prenovost, who continually worked to help me find the appropriate data.

Kristin Fong took the time to meet with me and supply me with data for this study. Paul

Castro and Trent Maggard gave their time as well. A final ‘thank you’ goes to Adam

Luskin and Sarah Sypniewski for their superb editing.

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 7

Abstract

Over the last few decades, many institutional investors, such as university endowments,

have jumped on board a new investing bandwagon: alternative assets. Why? Ivy League

endowments – with elite money managers at the helm – have posted extremely

impressive risk-adjusted portfolio returns using alternative assets.

Alternatives are those investments that are not investments in stocks, bonds or

cash. This asset class includes a wide range of investments, including hedge funds, oil &

gas, timberland, real estate, venture capital, mergers and acquisitions, and even fine art.

There is no accurate indexing option for alternative assets. To invest in alternatives,

active management is required.

Previous studies have demonstrated that university endowments can often yield

higher investment returns through index-based investing strategies as opposed to

actively-managed alternative investments. Put simply, low-cost indexing produces higher

returns. Only the largest institution can afford to retain the best money managers.

Therefore, the best investment strategy is to retain those managers. The second-best

strategy is to hold an inexpensive index fund. The worst strategy is active management

by a pedestrian money manager.

These studies omit one critical variable: risk. A basic tenet of investing that is

higher investment return can only be realized by subjecting principal to higher risk.

While the index fund may post a higher a return, it may also subject the investment to

higher risk. These studies failed to measure risk-adjusted performance.

This study seeks to examine the value of holding alternative assets without

management by elite professionals. Metrics for consideration include not just total return,

but volatility (standard deviation), risk-adjusted performance (Sharpe Ratio), risk-

adjusted performance above a minimum threshold (Sortino Ratio), and investment

performance in years of market shock – including the bursting of the tech bubble and the

sub-prime crisis.

Eight case studies are considered, measuring the value of alternative assets.

Results show that index-based portfolios not only produced higher returns, but it did so

with less volatility (risk) and exhibited superior performance during market shocks.

Endowments allocating to alternatives should carefully re-evaluate their investment

strategies.

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 8

Chapter 1: Introduction

Scope

Without perceived sufficient in-house expertise, non-profit organizations often transfer

management of their multi-million dollar investment pools to outside firms (Jones and

Martinez 2013). These firms often put the non-profit’s funds into expensive and complex

investment vehicles.

Impressed with the returns of the Ivy League investment pools, and persuaded by

professional money managers, non-profit boards and executives are allocating

increasingly larger portions of their investments to alternative assets (National

Association of College and University Business Officers and Commonfund Institute

2012). Yet in the absence of Ivy League resources (i.e. access to top-decile

1

money

managers), these non-profits are witnessing inferior investment returns – most certainly

less than could be had by holding a basket of diversified index funds (Ferri 2012,

Wallick, Wimmer and Schlanger 2012). The reason for this poor performance is that

smaller institutions simply do not have the scale to reward truly skilled investments

managers with millions of dollars in compensation.

Further, while the Ivy League endowments have previously consistently posted

superior investment returns, recent performances have been inconsistent (Yale

Endowment 2012, Mendillo 2012). This is in part because the once inefficient market for

alternatives has grown increasingly competitive as more imitators crowd into the

marketplace.

Given the asset class’s poor performance record, what is the reason for this

allocation to alternatives? This paper seeks to evaluate the risk-adjusted return of holding

alternative assets when not managed by top-decile professionals. In the empirical study to

follow, eight non-profit investment pools with assets under management (AUM) under $1

billion are evaluated. Investment performance is juxtaposed against a portfolio absent of

alternative assets.

Orientation

With hundreds of millions of dollars on the line, a foundation’s annual investment return

determines exactly how much the charitable organization can do each year. Higher

investment returns mean more grants, meals served, scholarships made available, or

medication distributed. Choosing the best investment strategy greatly impacts achieving

an organization’s mission.

1

The top-decile being those investment managers above the 90

th

percentile with respect to

creating risk-adjusted return.

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 9

One investment strategy in particular, the utilization of active management,

2

makes the promise of stock market-beating returns. However, actively-managed funds

fail to beat their respective benchmark over 90% of the time (Bogle 2007; Malkiel 2012;

Swensen; Bernstein 2010; Stanyer 2010). In the likely event of poor investment

performance, investors are still liable for paying expensive management fees. These fees

for actively-managed investments can reach two percent annually – sometimes more.

3

With non-profits’ using investment gains to fund programming, market

underperformance by two percent can mean cutting back on programming services for

the year. A two percent loss compounded over 10 years can mean shutting down entire

departments.

Figure 1 - $31,000,000 Difference on a $100,000,000 Investment

Given the poor track record of active management, why are non-profits putting increasing

proportions of their money into alternative investments? Non-profit executives and board

members do not believe they have the skill set to invest the money themselves.

4

Thus,

they outsource the role to professional money managers. However, for many

organizations, their limited assets of only several hundred million dollars preclude them

from being able to hire the best of the best: the top-decile money manager.

Thus, these organizations hire average money managers, who pitch the value of

diversification in holding exotic alternative investment products (McCrum 2013).

However, performance data of alternative endowment investments has shown the returns

2

Alternatives are a type of actively-managed asset. Conventional assets can also be actively

managed. The distinction between the two is covered in a following section The Endowment

Model and Alternative Assets.

3

Hedge funds are an example of this. Hedge funds typically have a 2 and 20 fee structure. This is

where fund management claims 2% of all AUM, and then another 20% on top of any gains.

4

As I will show in this paper, this is not the case. A simple index-based strategy is easy to

execute. Any CFO could more than manage the task.

$179,084,770

$148,024,428

$100,000,000

$110,000,000

$120,000,000

$130,000,000

$140,000,000

$150,000,000

$160,000,000

$170,000,000

$180,000,000

$190,000,000

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Investment Value

Period (Years)

6% Return Compounded

4% Return Compounded

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 10

offered by active management are usually less than what could be had with indexing

(Ferri; Wallick, Wimmer and Schlanger).

If studies have already proven the superior returns of indexing over average active

management within non-profit investment pools, why does active management still exist?

Why do boards of non-profit organizations and finance committees - staffed by

seemingly knowledgeable, competent professionals - continue to invest in a failed

strategy?

One reason is the just-mentioned value of diversification. Maybe these poorer

performing alternative assets help a portfolio produce superior risk-adjusted returns. That

is, for the level of risk involved, adding alternatives creates a better investment. Including

actively-managed alternatives (even when managed by average money managers) may

offer a way to reduce risk and even achieve superior risk-adjusted returns because of low

correlation to market events.

Personal Background

Prior to my research for this project, my personal investment strategy consisted of

chasing temporally high-flying mutual funds. Such behavior was egged on by broker

suggestions, who neglected to mention the issue of volatility. Never once did a broker

say, “your limited assets prevent you being able to hire a manager who can beat the

market after the cost of fees. It is those fees – in the absence of superior performance –

that will eat away at returns. Your best bet is to buy and hold the lowest cost index fund

available.”

If this simple advice was not available to me, with my small retirement portfolio,

what chance is there that an outside adviser would suggest the same to a non-profit

organization, especially when there are literally millions of dollars in fees on the line?

Conceptual Framework

Non-profit and governmental organizations have billions in invested assets. Much of this

wealth is concentrated in educational endowments and pension funds, respectively.

Historically, most of these funds were invested in a mix of corporate stock and

government bonds. However, within the last few decades, a shift in investment strategy

has occurred (Ezra 2012, Swensen). Before this paper covers the consequence of that

shift in detail, an investing primer follows. Readers already familiar with the basic tenets

of Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT), diversification and correlations, and the endowment

model and alternative assets, can skip to section Questions to Be Addressed in This Thesis

on page 16. For a primer on indexing and active management, see Appendix A: Indexing

vs. Active Management on page 58.

Correlation & Modern Portfolio Theory

Correlation is the extent to which one asset’s performance mimics another asset’s

performance. Consider an example: Investment A increases in value by 100%.

Investment B increases in value by 50%. Investments A and B are said to have a

correlation of 0.5. For every increase (or decrease) Investment A undergoes, Investment

B undergoes ½ of that increase (or decrease).

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 11

The following line graph, Figure 2 - Asset Class Correlation, illustrates

correlation.

5

Consider how the performance of the S&P 500 (blue) is highly correlated to

the performance of international companies (purple). The blue and purple lines rise and

fall simultaneously. When blue is up, purple is up. When blue is down, purple is down.

Thus, the performance of domestic equities (S&P 500) and international equities are

highly correlated.

Figure 2 - Asset Class Correlation

Conversely, long-term Treasuries are historically negatively correlated to the S&P 500

(Swensen). Note that in the graph, the long-term Treasuries (red) make opposite moves in

value relative to the S&P 500 (blue). When blue is up, red is down. When blue is down,

red is up.

Commodities theoretically exhibit little correlation to the other asset classes just

mentioned. Consider how commodities (green) rise and fall relatively independently of

the other asset classes.

According to Modern Portfolio Theory, a portfolio of investments performs best

when it is diversified among assets that have no correlation. Since every asset suffers

from periods of poor performance, diversification across uncorrelated asset classes

ensures consistent portfolio growth.

The Endowment Model and Alternative Assets

The strategy for institutional investors has changed over time. Before 1980, corporate

stock and government bonds (60/40) represented the norm. In the early 1980’s, a new

investing strategy came into fashion, dubbed the endowment model or Yale model (Ezra).

Under their Chief Investment Officer, David F. Swensen, Yale University gave birth to

the endowment model. Swensen pioneered this investment strategy, which received

attention for its consistent market-beating returns. Distinguishing Yale’s strategy from

traditional investment paradigms is its ever-increasing allocation to alternative assets

(2012 Yale Endowment).

5

These are the not the actual returns of the listed asset classes. The example is solely for

explanative purposes.

0.7

0.9

1.1

1.3

1.5

1.7

1.9

2.1

2.3

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

Growth of Wealth

S&P 500

Long term Treasuries

Commodities

International

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 12

Distinctions of Alternative Assets

Alternative assets are those investments outside of conventional stocks and bonds.

Alternatives include hedge funds, real estate, timberland, oil and gas, precious metals,

venture capital, merger and acquisitions, and fine art.

6

Alternative Investment Class

Strategy

Hedge Fund

Absolute Return

Oil & Gas

Real Assets

Timberland

Real Assets

Precious Metals & Mining

Real Assets

Real Estate

Real Assets

Venture Capital

Private Equity

Mergers & Acquisition

Private Equity

Fine Art

Speculative

Several distinctions separate alternatives from conventional assets. What follows are the

distinctions relevant to this study. (The breadth of content precludes a full discussion of

these distinctions.)

Correlation: Holding alternative assets can help diversify a portfolio. A lure of

alternative assets classes is their low correlation to conventional assets (Malkiel).

Recall the performance of commodities displayed in Figure 2 - Asset Class

Correlation on page 11. Put another way, what makes alternatives appealing is

the idea that their investment return is relatively independent of broad stock

market movements.

Inefficient Markets: Alternatives trade in inefficient markets. This in contrast to a

publicly-traded company, where information relevant to the company’s value is

readily accessible within seconds. The rapid availability of this information is

instantly reflected in that company’s share price. This is the opposite case for

alternative investments. Whereas information about the investment value of

conventional assets (e.g. a publicly-traded company) is widely accessible through

mass media, comparable information is not available for most alternative

investments (e.g. several acres of privately-held timberland). A truly skilled

money manager can exploit this information asymmetry for superior risk-adjusted

investment return. Recent crowding into these markets, however, has decreased

this potential (Humphreys). Therefore, the market for alternatives assets is

becoming increasingly efficient. This is reflected in the poorer investment returns

of Ivy League endowments relative to an indexed investment (Yale Endowment).

6

Fine art, like gold, is a speculative investment. Speculative investments depend solely on price

appreciation, providing no income (i.e. paying no dividend). No case study in this paper engaged

in fine art as an investment vehicle.

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 13

Active management: Alternative assets require active management (Swensen

2009). Unlike conventional stocks and bonds, there exists no true index fund for

alternatives.

7

Illiquidity: Alternatives assets are those assets that trade in smaller, illiquid

markets. Whereas a share of Apple stock can be sold within a millisecond on the

New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) for the market price, transferring ownership

of a private company may take weeks or even months to execute. Such trading

illiquidity risk requires compensation; illiquid assets must sell at a discount

relative to liquid assets of equal value (Celati 2005).

For investment pools that have regular distribution requirements, illiquidity can be

problematic if significant allocations of an investment portfolio are illiquid. Consider

endowments providing operational support, pension funds, charitable foundations making

the required distribution of 5% annually, or even individual retirement portfolios that

provide for cost of living in the absence of other income. An over-allocation of illiquid

assets may mean that an investor is not able cash in the event of an emergency. This is

illiquidity risk: “risk of losses due to the need to liquidate positions to meet funding

requirements,” (Jorion 2012). Further, this liquidity risk is difficult to measure. Jorien

explains:

…liquidity risk creates a major problem for the measurement of risk. After

all, risk measures represent potential changes in market prices. If

historical prices do not change frequently enough, traditional risk

7

While there are some investment products that attempt to index alternatives, most fail in their

execution. Either these investments do no accurately track the price of the sector they intend to

mimic, or excess fee eat away at returns. Real estate is the exception. Many real estate

investments are available via inexpensive Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) indices.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Level I Investment

Highly Liquid

Level II Investment

Relatively Illiquid

Market Price Relative Underlying Asset

Value

Illiquidity premium - Discount to

asset's underlying value

% of Asset's Underlying Value

Reflected in Market Price

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 14

measures cannot be accurate. Worse, they will tend to underestimate the

true economics risks.

The infrequent measurement intervals of alternative assets grossly understate volatility

(risk). Risk-adjusted metrics therefore are less valuable when comparing liquid and

illiquid investments. It’s essentially an apples-to-oranges comparison. The more illiquid

an investment is, the more difficult it is to assess its volatility. When correcting for

infrequency of available data, one study has shown private equity to be more volatile than

conventional assets. Given this, the study’s authors deemed the asset classes unworthy of

investment (Conroy and Harris 2008)

Over allocating illiquid assets can be problematic. Consider that the recent sub-

prime crisis forced many endowments to sell assets at depressed levels (Humphreys).

Further, selling liquid assets ultimately increases the percent of illiquid assets in the

portfolio, exacerbating the illiquidity problem.

Types of Alternative Assets

Distinctions between the various types of alternatives assets are covered briefly below. A

full discussion is beyond the scope of this paper.

Hedge funds, using an absolute return strategy,

8

theoretically perform

independent of market movements. This is because hedge fund managers have the

ability to take either the position that an investment will appreciate in value (long)

or depreciate in value (short). This is different from traditional mutual fund

managers, who can only be long in a position. After accounting for the fees of

hedge funds – usually 2% of AUM and 20% of any investment return – data has

shown hedge fund managers have failed to beat the benchmark consistently

(Jorion, Swensen, Kolhatkar 2013). This is because most of hedge fund

investment successes are consumed as fees before that return ever makes its way

back to the investor (Bhardwaj, Gorton and Rouwenhorst). Further, hedge fund

managers dictate strict rules for divestment, imposing lockup and minimum

redemption notice periods (Swensen; Jorion). Such constrained exit liquidity –

“the speed with which one can liquidate the investment in a fund” – is risk

(Celati).

Real estate is considered an alternative asset because it is neither a stock nor

bond. When it comes to investing in real estate, there are several options. On the

inexpensive end of the spectrum and requiring the least manager skill is a Real

Estate Investment Trust (REIT) index fund. A REIT index gives an investor a low-

cost way to diversify across numerous real estate holdings. Edging closer to active

management, an investor may choose to select specific REITs, or may hire a

money manager via an actively-managed mutual fund to do so. Privately

managed, real estate is at the other end of the cost and liquidity spectrum.

8

Absolute return investment techniques involve using short selling, futures, options, derivatives,

arbitrage, leverage and unconventional assets.

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 15

Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs) are investments in the petrochemical

transport infrastructure. (Diversification in MLPs can be achieved with

moderately-priced index funds.)

9

Commodities investments range from holding physical assets (like gold bullion) to

investing in a trust that holds gold for an investor, minus an ongoing fee. The

challenge for such an investment is that the commodity must appreciate in value

in excess of inflation to cover the cost of management, storage and transactions.

Because the asset does not produce income, a speculative commodity investment,

such as gold, is risky.

Private Equity is ownership in privately-held companies. Venture capital (VC)

and mergers and acquisitions (M&A) are the two categories of private equity. VC

is the process of investing in a new privately-held company. In this type of

investment, skilled money managers make all the difference. Top-decile managers

know how to pick the winning start-ups, and further have the skill set to make

those start-ups successful. Mergers and Acquisition is the process of purchasing

companies using severe leverage (debt) with the intent to restructure, and

ultimately to resell the company. Here again, the manager’s skills makes the most

difference. Problematic is that the best private equity firms are closed to new

investors (Swensen).

The Bandwagon

When other institutional investors saw Yale’s superior returns, they made the connection

that superior performance could be had by investing in alternatives. Without fully

comprehending the distinctions of alternatives, these institutions rushed into this new

asset class. Unfortunately, these imitators missed the critical variable that determined

Yale’s success: Yale.

Yale’s superior performance is only partially due to its asset allocation. The real

driving factor is superior money manager skill. With billions of dollars under

management, and as a breeding ground for some of the brightest minds, Yale is able

to attract and groom the best money managers in the world. Further, Yale’s success

is also due in part to their very aggressive investment strategy. Being first into the

alternative asset classes, Yale was able to take advantage of the then-inefficient pricing of

alternative assets. A crowded alternative assets market has made more recent superior

risk-adjusted returns harder to come by (Humphreys, Yale Endowment). What was once

an inefficient market has become increasingly efficient – decreasing the opportunity for

excess returns.

The result of smaller institutions jumping on board the alternative bandwagon was

predictable. In the absence of superior manager skill and in the absence of having the

advantage to being first in line, the copycat institutions posted relatively smaller

investment gains. Average active managers dealing in alternative assets in today post

9

The cheapest MLP indexes (ticker MLPA & MLPX) can be had for 45 basis points, or 0.45%.

Not expensive, but not cheap relative to an S&P 500 index fund at just two (2) basis points.

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 16

returns similar to average active managers dealing in conventional assets: less than what

could be had with an index fund (Swensen). If return alone is the goal of the investor,

then the small-time investor is best served by completely avoiding alternative assets.

However, alternative assets offer another value as briefly mentioned above: low

correlation.

Questions to Be Addressed in This Thesis

This paper examines the investment pools of institutions with AUM between $3 and $600

million. These multi-million dollar institutional investors (hereafter MMII) are distinct

from those institutions with investments pools in excess of $1 billion because they do not

have the scale required to retain top-decile money managers. MMII are best served by

utilizing an index fund strategy. This means avoiding alternative assets because

alternatives offer no real index fund (Swensen).

But what about the low correlation offered by alternatives – does the value of low

correlation mean that is there a role for alternative assets in the portfolios of MMII? With

low correlation – but with high fees – can alternative-laden portfolios serve to cushion

MMII from market shocks felt by investors holding only conventional assets?

Consider volatility. Hypothetically, alternative assets could act in a fixed income-like

fashion, keeping the entire portfolio more buoyant against market crisis. Better still, the

higher return potential of alternatives would produce superior returns relative to fixed-

income products. Alternatives, even in the hands of an average money manager may offer

lower returns but superior risk-adjusted performance.

This paper seeks to answer the question: Will a portfolio with allocation to

alternatives between 14% and 38%, without top-decile management, underperform

an index-based portfolio, but still produce superior risk-adjusted returns?

The Most Important Concepts and Their Definitions

The following section explains the investing metrics mentioned in this study. More basic

investing concepts are covered in Appendix C. Readers already familiar with the

concepts of standard deviation, Sharpe Ratio, and Sortino Ratio can skip to Chapter 2:

Overview on page 19.

Standard Deviation is calculated by computing the square root of how far a set of

numbers is spread out (variance). Standard deviation is a function of variability in

returns; it is a measure of volatility or risk. (The terms standard deviation, risk, and

volatility have the same meanings and are referred to interchangeably throughout this

paper.) A higher standard deviation means that fluctuations in investment returns are

more pronounced. Risky assets (like stocks) have higher standard deviations than less-

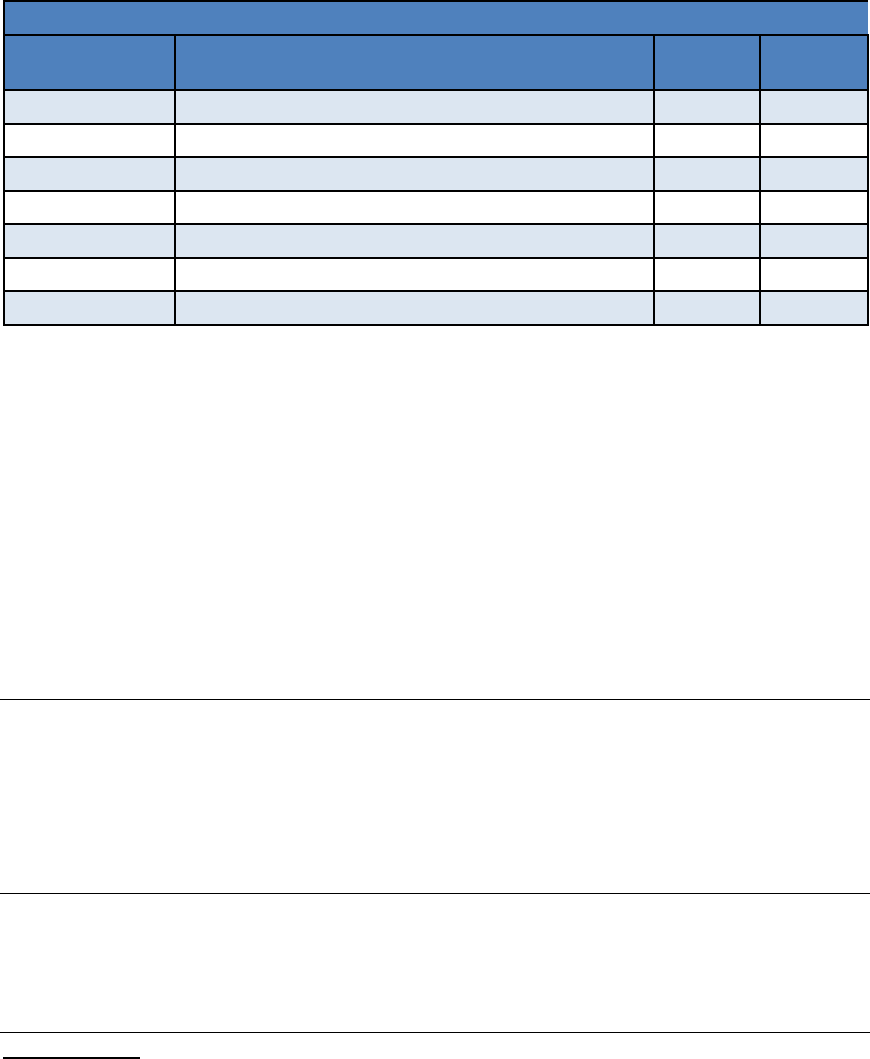

risky assets (such as bonds). See the following tables Table 1 - Standard deviation

illustration.

The portfolio on the left, with annual returns varying from as high as 10% to as

low as negative 5%, has a standard deviation of 6.2%. The portfolio in the middle, with

returns varying between 1% and 2% per year, has a much lower standard deviation of 0.4

%.

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 17

Risky Portfolio

Safe Portfolio

Bad Portfolio

Year

Return

Value

Return

Value

Return

Value

0

$100.00

$100.00

#$100.00

$100.00

$100.00

$100.00

1

5.00%

$105.00

105.00

2.00%

$102.00

-1.00%

$99.00

2

10.00%

$115.50

115.50

1.00%

$103.02

-1.25%

$97.76

3

-5.00%

$109.73

109.73

1.50%

$104.57

-1.00%

$96.78

Total Return

9.73%

4.57%

-3.22%

Annualized

Return

3.14%

1.50%

-1.08%

Standard

Deviation

6.2%

0.4%

0.1%

Table 1 - Standard deviation illustration

All else being equal, the lower the standard deviation, the better. However, standard

deviation can be a misleading metric because it is a strictly a measure of volatility, not

value. For example, the ‘Bad Portfolio,’ with a negative return, actually has the lowest

standard deviation of all.

Sharpe Ratio is a measure of how well an investor is rewarded for bearing risk. It is a

measure of risk-adjusted performance. The Sharpe Ratio is a mathematical metric that

takes both risk and return into account. As risk goes down, or return goes up, the Sharpe

Ratio increases. Conversely, as risk goes up, or return goes down, the value decreases.

The Sharpe Ratio is calculated as the return (minus the risk-free rate) divided by risk.

10

Risky Investment Portfolio

Safe Investment Portfolio

Year

Return

Investment

Value

Return

Investment Value

0

$100.00

$100.00

1

5%

$105.00

2%

$102.00

2

10%

$115.50

1%

$103.02

3

-5.00%

$109.73

1.50%

$104.57

Total Return

9.73%

4.57%

Annualized Return

3.14%

1.50%

Standard Deviation

0.062

0.004

Sharpe Ratio

0.40

2.50

Table 2 - Sharpe Ratios

In the preceding Table 2 - Sharpe Ratios, the “Risky” portfolio generated annualized

returns in excess of 1.64% per annum over the “Safe” portfolio (3.14% versus 1.50%).

10

See Appendix A: Indexing vs. Active Management

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 18

However, the “Risky” portfolio netted a much lower Sharpe Ratio. Because of the

volatility required to generate those excess returns, the Sharpe Ratio deems the higher-

returning portfolio inferior. The Sharpe Ratio declares that it is not worth the risk

required to generate the higher returns. Higher returns are less valuable in this instance

because there was so much additional risk required to realize those higher returns.

Sortino Ratio is similar to the Sharpe Ratio, but where the Sharpe Ratio gives higher

scores to a portfolio for producing substantially higher returns with slightly higher risk,

the Sortino Ratio gives lower scores to portfolios that fall below a certain performance

threshold. For the case studies to follow, that threshold is set at 5% per annum.

11

Though an arguably aggressive withdrawal rate, certain charitable foundations are

required to spend 5% annually or face tax penalties.

12

Risky Investment Portfolio

Safe Investment Portfolio

Year

Return

Investment

Value

Return

Investment

Value

0

$100.00

$100.00

1

5%

$105.00

2%

$102.00

2

10%

$115.50

1%

$103.02

3

-5.00%

$109.73

1.50%

$104.57

Total Return

9.73%

4.57%

Annualized Return

3.14%

1.50%

Standard Deviation

0.062

0.004

Sharpe Ratio

0.4

2.5

Sortino Ratio

-0.28

-0.99

Table 3 - Sortino Ratio

Why the Sortino Ratio? Non-profit organizations rely on their endowment pool to fund

ongoing operations. If an investment portfolio is unable to consistently produce returns

above a minimum required amount, that investment portfolio is not appropriate. With the

Sortino Ratio, portfolios can be evaluated on their consistency of posting returns above a

required minimum.

Consider the preceding example in Table 3 - Sortino Ratio. Though the Sharpe

Ratio scored the “Safe Investment Portfolio” as more valuable, the Sortino Ratio gives

the “risky” portfolio the higher score. This is because for the Sortino Ratio, a portfolio

that cannot produce returns in excess of 5% annually is not as valuable as one that does,

all else being equal. The higher Sortino Ratio, the better the portfolio.

11

5% is a conventional withdrawal rate for foundations.

12

Endowments are exempt from taxation.

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 19

Chapter 2: Literature Review

Overview

The literature studied includes several topics:

Basic investing principles

Studies of active management efficacy

Indexing investment

History of institutional investing

Endowment model of investing

Non-profit board member fiduciary requirements

Analysis of historical performance of institutional investors: universities,

hospitals and other non-profit organizations

Summary of Major Sources

Pioneering Portfolio Management is the authoritative guide on how to produce an

investment portfolio based on the endowment model.

A Random Walk Down Wall Street examines the efficacy of active management.

The Little Book of Common Sense Investing is an argument for passive management,

made by the pioneer of index funds.

NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowments is a statistical report of over 800

endowments across the nation.

Unconventional Success determines inappropriate versus superior investment strategies

for retail investors.

2012: The Yale Endowment is the annual endowment report by Yale’s Chief Investment

Officer, outlining endowment performance and investment strategy.

Once upon a time… is a historical review of investment strategy of nonprofit

organizations.

Educational Endowments and the Financial Crisis examines the weaknesses and social

consequences of the endowment model of investing.

The Curse of the Yale Model compares existing endowment returns relative to the

performance of indexed-based portfolios.

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 20

Assessing Endowment Performance is another index-versus-endowment return

comparison.

For a complete digest of the literature, see Appendix E: Digest of the Literature on page

67.

Methodology

The investigative approach and methods used by the authors in the literature:

Commonfund Institute’s annual publications provide statistical data on

institutional investors’ performance. This data includes statistical breakdown

by such metrics as asset allocation by institution size, return performance by

institution size, and return performance by asset class. There is no

consideration for volatility. Commonfund acquires this information via survey

(Commonfund Institute; National Association of College and University

Business Officers and Commonfund Institute).

The how-to guides, published by investment services companies catering to

non-profit organizations, list fiduciary responsibilities of board members with

respect to an investment pool. These guides explain the evolution of those

fiduciary responsibilities and suggest various investment policy practices to

fulfill those responsibilities. Discussed are investment policy statement

requirements (templates are provided) and portfolio manager selection and

evaluation criteria (Merrill Lynch Center for Philanthropy & Nonprofit

Management; Commonfund; Towers Watson Investment Services; Steele,

Prout and Larson).

Two brief comparisons pit the returns of the average endowment – as

published in the Commonfund study mentioned above – against hypothetical

performance of a portfolio of index funds for the same timetable (Ferri;

Wallick, Wimmer and Schlanger).

The more academic portion of the literature cites studies on the performance

of various investment strategies – sometimes their own – and provides

anecdotes for illustration (Bogle 2007, Bernstein 2010, Swensen 2005,

Malkiel 2012, Stanyer 2010).

Overall Summary and Comparison

What is Known about the Topic

Without retaining top-decile active management, investors are best served by adopting a

portfolio of low-cost, index-based funds, utilizing a buy-and-hold strategy (Bogle;

Bernstein, Malkiel; Stanyer; Swensen).

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 21

Alternative assets require active management (Swensen).

In two brief comparisons, a buy-and-hold, low-cost index-based portfolio outperformed

the returns of the average endowment more often than not (Ferri 2012, Wallick, Wimmer

and Schlanger 2012).

Institutional investors of all sizes suffered a liquidity squeeze during the recent market

downturn, in part because of the illiquid nature of alternative investments (Humphreys

2010, Asch 2010).

Endowments have been consistently increasing their exposure to alternative assets

(Commonfund Institute 2012, National Association of College and University Business

Officers and Commonfund Institute 2012).

What is Unknown

While indexing strategies outperform, there is no analysis of volatility. Does the risk-

adjusted return of actively-managed investments for MMII outperform conventional

assets due to lower volatility?

Major Similarities within the Literature Reviewed

Without retaining top-decile management, a strategy of buy-and-hold index-based

investing is superior.

Differences within the Literature Reviewed

Appropriate asset allocations – and what defines an appropriate asset – are in debate.

Controversies in the Literature

Despite the growing amount of endowment model practitioners, it has its critics. These

critics point to the liquidity squeeze suffered in the midst of the recent sub-prime crisis.

Other critics point to an inappropriate role reversal between the endowment and

university programming; programming being cut for the purposes of preserving the

endowment (Humphreys). Another point of contention is the lack of transparency

inherent in alternative assets (The Responsible Endowment Project 2010, The

Responsible Endowment Project 2009).

Critique

Inconsistencies

Though it is not the subject of this study, authors do not agree on a single investment

strategy; they are not in consensus on the ideal asset allocation nor those asset classes that

are suitable for investment. Regarding the subject of bonds, some of the literature

suggests emerging bonds or corporate bonds as appropriate investments (Stanyer).

Another argument is made for the exclusive holding of long-term Treasuries (Swensen); a

third for the exclusive holding of short-term bonds – with no specification made as to the

bond issuer (Bernstein).

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 22

Strengths

The portion of the literature from the academic community makes a strong case for index

investing in without retaining top-decile managers. This idea is supported by extensive

studies.

Weaknesses

While Ferris and Vanguard’s comparison of investment returns are revealing, they fail to

include a critical variable worthy of examination: volatility. Yes, index investing

outperformed active management. However, what was the volatility of the returns? Is it

superior risk-adjusted performance? Is such volatility appropriate for an endowment?

Those subjects are not discussed. Without that information, it cannot be concluded

whether alternatives are an appropriate investment vehicle for MMII. The specific point

missed is that the value added by alternatives is not necessarily superior returns. It is

diversification and low correlation to conventional asset classes.

Some of the literature reviewed was removed from inclusion because of specious

reasoning. For example, one book cited a separate study as an authoritative source to

prove its argument. The study stated that the inclusion of commodities in an investment

portfolio is a good medium for achieving diversification. That study was funded by a

company in the business of producing commodities, and therefore represents an obvious

conflict of interest.

The less academic portion of the literature suggests a wide range of questionable

investment strategies, including charting (technical analysis or ‘trend following’) and

investing in unproven assets with high management fees (Parness 2002, Richardson and

Faber 2009, Tuttle 2009).

Gaps

The idea of the total value added by alternatives, outside of returns (volatility, risk-

adjusted returns), is not explored.

Limitations

Some of the literature reviewed showed substantial signs of conflicts of interest. The

how-to guides by investment services companies are examples of this.

Point of Departure

This empirical study seeks to address the value added by active management and

alternative assets within the endowment portfolios of eight non-profit investment pools.

Not only will it analyze total return, but also the volatility of annual returns (standard

deviation), considerations for the value of returns relative to risk (Sharpe

13

& Sortino

Ratios), and portfolio performance in times of market crisis.

13

See Appendix A: Indexing vs. Active Management

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 23

Chapter 3: Empirical Study Method

Hypotheses

This study seeks to test the following hypothesis:

Investment pools will underperform index-based portfolios (in part because of the

effect of fees), but will experience less volatility and superior returns in times of

market crisis (because of the diversification value of alternative asset allocation).

Said another way, alternative-laden portfolios will forfeit higher returns in exchange for

less volatility when compared to portfolios without alternative asset allocation.

Specifically, alternative-laden portfolios will outperform conventional portfolios in years

of market crisis. For the purposes of this study, market crisis is defined as the bursting of

the internet bubble (Fiscal Year (FY) 2001-3); the sub-prime crisis (FY 2008-9); and the

more recent poor performance of international and small domestic companies (FY

2012).

14

These periods of poor market performance are referred hereafter to as ‘bad

years.’

What follows is the description of a simple index-based portfolio. The

performance of this comparison portfolio will be used to evaluate the following case

studies. Also, included as points of reference is the conventional 60/40 benchmark as

well as the S&P 500.

15

For more about these benchmarks, see Appendix D: 60/40

Benchmark on page 63 and Appendix A: Indexing vs. Active Management on page 58,

for the 60/40 and S&P 500 respectively.

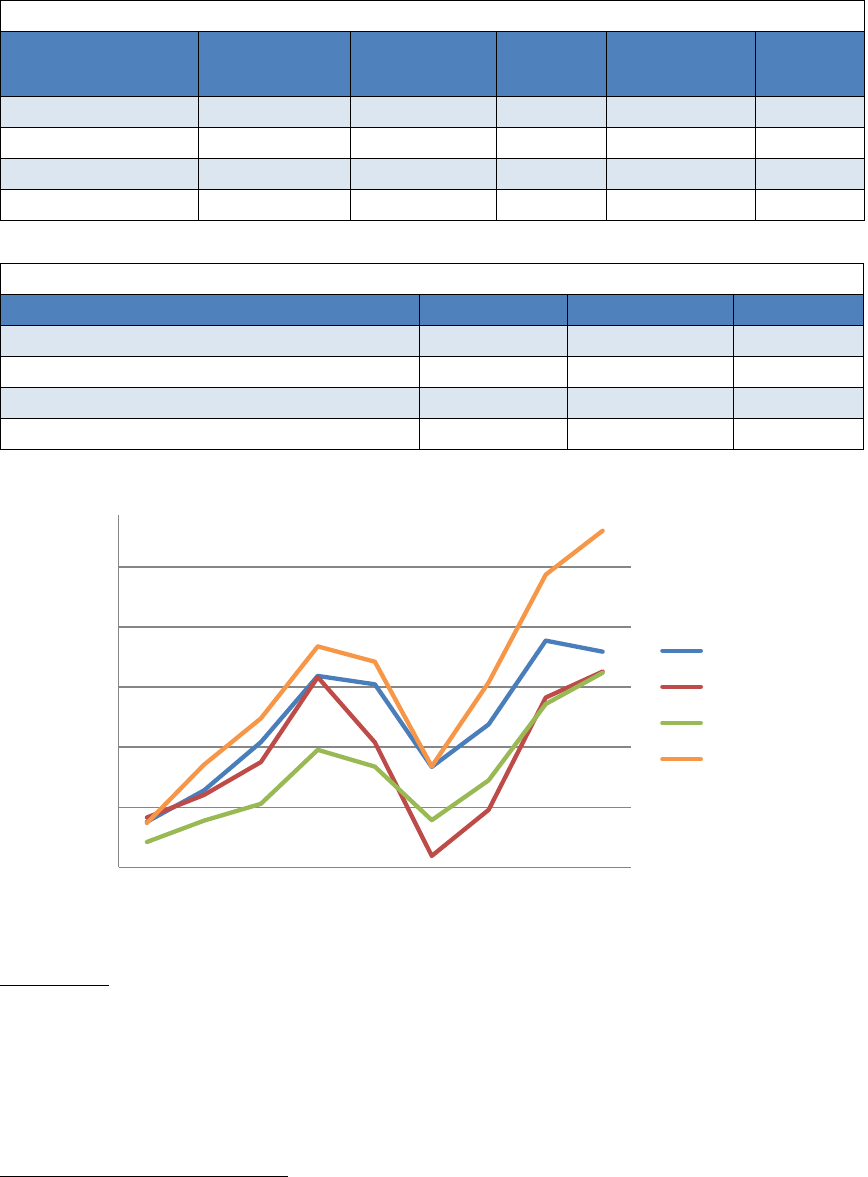

Swensen Portfolio

David Swensen, Chief Investment Officer at Yale and pioneer of the “Endowment

Model,” suggests a boiler-plate portfolio for those that do not have the resources to retain

top-decile active management. This suggestion applies to retail investors and MMII alike.

This low-cost index fund model specifies diversification across six distinct asset classes:

15% long-term Treasuries, 15% inflation-protected Treasuries, 20% Real Estate

Investment Trust (REIT) index, 5% emerging markets index, 15% foreign developed

markets index, and 30% US stock market index. See the following Table 4 - Asset Class

Allocations of Swensen Portfolios.

14

Endowments are reporting that “International equities and real assets were affected by the

debt and sovereign crisis in the Eurozone as well as slowing growth in China and other emerging

markets” (Wo, University of Hawaii Foundation 2012 Endowment Report).

15

Performance all benchmarks were calculated using DFA Returns 2.0.

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 24

Asset Class Allocations – Swensen Portfolios

Asset Class

Index

Swensen

Swensen

65/30/5

US Broad Market

Dow Jones US Total Stock Market Index

30%

25%

US REIT

S&P United States REIT Index (gross dividends)

20%

20%

International

MSCI EAFE Index (gross dividends)

15%

15%

Emerging

MSCI Emerging Markets Index (gross dividends)

5%

5%

Treasuries

Barclays Treasury Bond Index Long

15%

15%

TIPS

Barclays US TIPS Index

15%

15%

Cash Equivalent

BofA Merrill Lynch 3-Month US Treasury Bill Index

0%

5%

Table 4 - Asset Class Allocations of Swensen Portfolios

In order to provide a relevant benchmark, the Swensen portfolio is modified to meet the

liquidity requirements of foundations making regular fund distributions. The rightmost

column in Table 4 - Asset Class Allocations of Swensen Portfolios, “Swenson 65/30/5”

allocates five percent to a cash equivalent. In addition to providing further liquidity, this

modification serves a second function: decreasing the volatility inherent in this portfolio.

Not only is the largest asset class (domestic broad market) reduced by 5%, but it is

replaced by a 5% cash equivalent that adds further stability. Moving forward, any

reference to the “Swensen portfolio” shall refer to the modified “Swensen 65/30/5”

discussed above. This portfolio is rebalanced annually.

Background of the Data Source

Case studies are non-profit organizations with AUM under $1 billion, which provided

data (either publicly or privately) on annual investment returns in excess of nine years.

Public data is sourced from annual endowment reports as posted on foundation websites.

Private data has been supplied directly to the author from participating institutions.

Procedure Used to Collect Data

Case studies were acquired via endowment publications, and by contacting organizations

individually for investment return data.

Advantages and Disadvantages of this Method

Selection Bias

While online research makes for expedient gathering of data, one problem with this

method is selection bias; the only information available is that which an organization

chooses to make public. This may exclude poorer performing investment portfolios for

the reason that the parties responsible do not wish to make their fund’s performance

public knowledge. While over 100 California-based non-profits were asked to participate

in this study, only one agreed – and only on the condition of anonymity.

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 25

The Bond Bubble

The time period evaluated is a unique one: two severe market downturns concurrent with

a rising bond bubble. With bond prices set to plummet at the culmination of the Federal

Reserve’s quantitative easing, the future for heavily bond-laden portfolios is bleak.

16

For

the period reviewed, the 60/40 portfolio exhibited strong performance, in part, because of

rising bond prices. How these portfolios perform in the future – amidst increasing interest

rates – will be entirely different.

Infrequent Data

There was only consideration of annual performance. Monthly or quarterly return data

was not available. Such infrequent measurements likely understate the true volatility of

the endowment portfolios under examination.

16

Bonds prices have an inverse relationship to interest rates. When interest rates are low, bonds

prices are high. With current interest rates at their lowest ever, bond prices are at their highest

ever. Any reversion of interest rates to historic averages (read: increase in interest rates) will

proportionally decrease the value of any bond.

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 26

Chapter 4: Findings

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 27

California Social Services Organization

California Social Services Organization

17

(hereafter CSSO), has $3.5 million AUM.

Without the resources available by having a large investment pool, CSSO is best served

by a strategy of buy-and-hold, utilizing low-cost index funds (Swensen 2009, Stanyer

2010). This, however, is the not the technique used by CSSO’s outsourced portfolio

manager. In fact, CSSO’s portfolio manager utilizes a doubly-opposite technique:

frequent trading of actively-managed mutual funds.

18

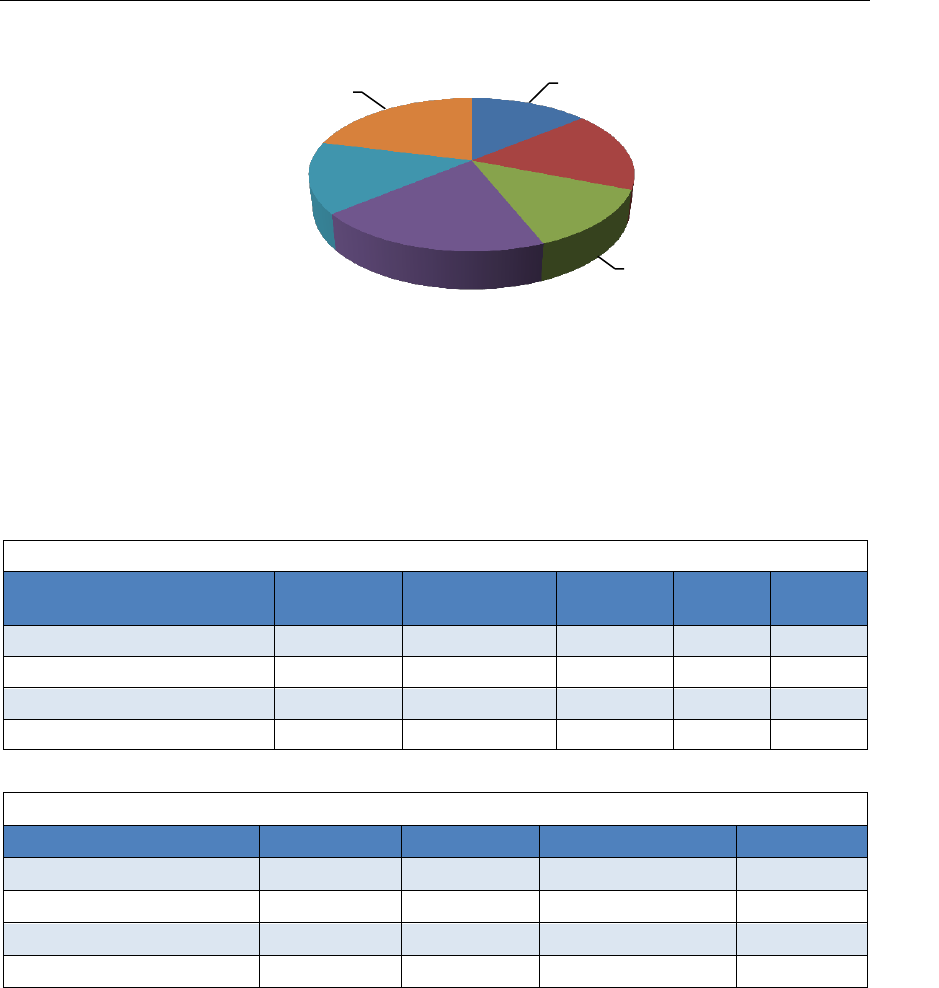

Figure 3 - California Social Services Organization asset allocation

Such a method of active trading, or market timing, is exactly what the literature review

advises against (Swensen, Malkiel 2012). Not only do actively managed mutual funds

usually fail to match market returns, but frequency of trading is inversely proportional to

the growth of wealth (Bogle 2007, Barber and Odean 2000). While such a trading

technique can be profitable, CSSO’s portfolio’s trade history shows multiple losses when

selling mutual funds for less than their initial purchase price. Such losses occurred on

numerous occasions. Ultimately, these losses were offset by gains, giving CSSO an

annualized return of 7.90% before fees. Based on the limited availability of data, CSSO’s

17

CSSO is not the real name of the organization. CSSO provided data for this project on the

condition of anonymity.

18

Such a mode would indeed be unbelievable, if not for the 10-year history of buy and sell

transactions made available by CSSO to the author.

Large Value

6%

Large Blend

6%

Large Growth

7%

Mid-Cap Growth

2%

Mid-Cap Value

2%

Small Growth

2%

Small Blend

2%

Foreign Large

Blend

6%

Foreign Small/Mid

Blend

3%

Diversified

Emerging Mkts

1%

Diversified

Emerging Mkts

Small Cap

2%

"Conservative

Hedge Fund"

10%

"Tactical Strategy"

8%

"Absolute Return"

6%

"Energy

Infrastructure"

6%

Multisector Bond

4%

Intermediate-Term

Bond

15%

3 month T-bill

13%

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 28

portfolio return net of fees is estimated to be 7.50% per annum.

19

See Table 5 - CSSO 10

Calendar Year Returns, Ending December 31st, 2012 for results.

CSSO 10 Calendar Year Returns, Ending December 31

st

, 2012

Index

Annualized

Total

STD

Dev.

Sharpe

Ratio

Sortino

Ratio

CSSO - gross of fees actual

7.90%

113.90%

18.05%

0.38

0.36

CSSO - net of fees, estimate

7.50%

106.15%

17.37%

0.4

0.32

S & P 500

7.10%

98.59%

18.32%

0.37

0.29

60/40

6.77%

92.46%

9.63%

0.53

0.31

Swensen - 65/30/5

9.78%

154.32%

13.41%

0.63

0.64

Swensen Portfolio

The index-based Swensen 65/30/5 generated a ten-year annualized return of 9.78%. The

Swensen model offers less risk (smaller standard deviation) as well. ‘Bad year’

performance was also superior: the Swensen model suffered a loss of -22.76% in 2009.

This is relative to CSSO’s 2009 performance of -33%. Further, in 2011, while CSSO was

generating negative returns, the Swensen portfolio posted a positive return of 5.7%.

19

See Appendix F: CSSO Net of Fees Estimate on page 118 for calculations.

Table 5 - CSSO 10 Calendar Year Returns, Ending December 31st, 2012

CSSO Calendar Year 2009 & 2011 Performance

Portfolio / Index

2009

2011

CSSO, gross of fees actual

-33.31%

-2.32%

CSSO, net of fees estimate

-33.68%

-2.67%

S&P 500

-37.00%

2.11%

60/40

-17.24%

4.88%

Swensen 65/30/5

-22.76%

5.70%

Table 6 - CSSO Calendar Year 2009 & 2011 Performance

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 29

Figure 4 – California Social Services Organization & comparison portfolio growth

Conclusion

The hypothesis states that actively managed portfolios, with their alternative assets, will

underperform benchmarks but will experience less risk. For CSSO’s portfolio just

reviewed, this was not the case. Instead of giving up higher returns in exchange for lower

volatility, CSSO’s outsourced portfolio manager generated lower returns with more

volatility. The hypothesis is rejected. Thus, CSSO’s portfolio manager provided less

value than the Swensen 65/30/5.

The following Table 7 - CSSO Portfolio Performance Relative Benchmarks

illustrates how the CSSO portfolio compares to benchmarks. A red cell indicates. A green

value represents outperformance. Against the Swensen portfolio, the CSSO portfolio

shows no instances of outperformance given the metrics under consideration.

CSSO Portfolio Performance Relative Benchmarks

Portfolio / Index

Annualized

Return

STD

Dev.

Sharpe

Ratio

Sortino

Ratio

2009

Return

2011

Return

S & P 500

0.40%

-0.27%

0.01

0.03

3.32%

-4.78%

60/40

0.73%

8.42%

-0.15

0.01

-16.44%

-7.55%

Swensen - 65/30/5

-2.28%

4.64%

-0.25

-0.32

-10.92%

-8.37%

Key

CSSO Superior Performance

CSSO Inferior Performance

Table 7 - CSSO Portfolio Performance Relative Benchmarks

Conflicts of Interest

Due to conflicts of interest, the manager was incentivized to over-trade holdings.

Therefore, the ability to accurately assess the value of alternative assets is compromised.

To learn about the conflicts of interest that manifest themselves in CSSO’s portfolio, see

Appendix G: CSSO’s Problematic Portfolio on page 101.

1.00

1.20

1.40

1.60

1.80

2.00

2.20

2.40

2.60

2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

Wealth Growfth Factor

CSSO, net of fees estimate

S&P 500

60/40

Swensen - 60/30/5

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 30

University of Hawaii Foundation

Suffering from negative returns in FY

20

2012, University of Hawaii Foundation (UHF)

stewards $201.5 million in AUM. Holding a mere 14 funds in 2004, this number more

than tripled to 50 funds by 2011. Only six of the original 14 remained in the portfolio by

the end of FY 2011.

21

Like California Social Services Organization (CSSO), UHF’s

portfolio manager trades holdings frequently. The average holding period for an

investment is just under three and a half years

22

(Wo n.d.).

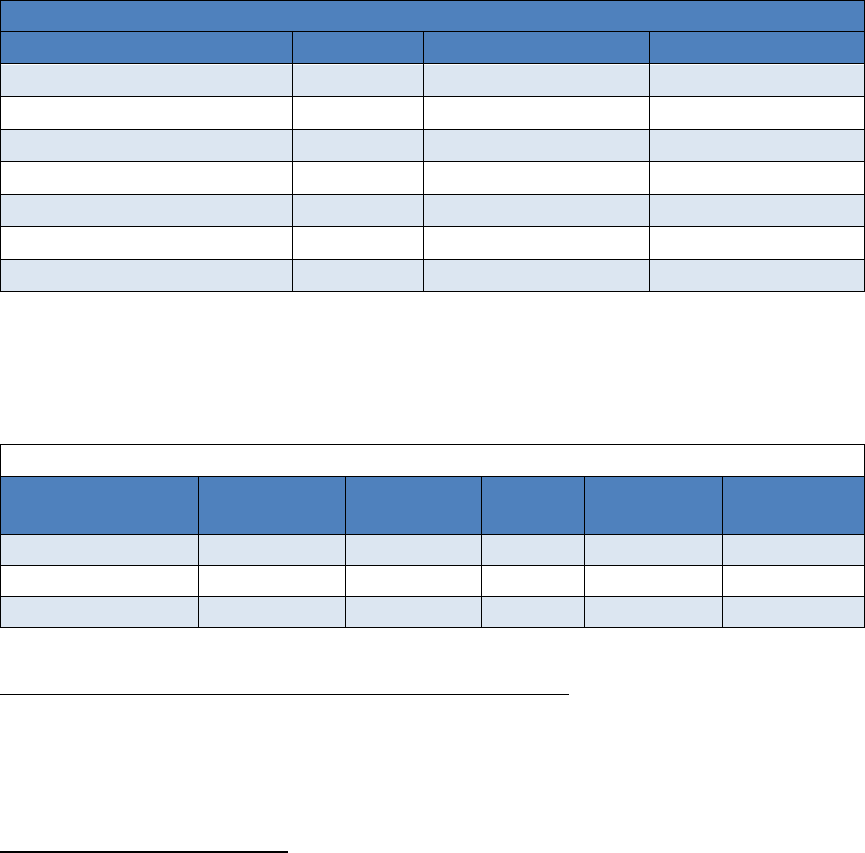

Figure 5 - University of Hawaii Foundation asset allocation

Swensen Portfolio

Relative to UHF’s portfolio, the Swensen portfolio produced exceptionally higher

returns, though with higher volatility (risk). See Table 8 - Performance Metrics of Nine

Consecutive FYs, ending June 30th, 2012 for the entirety of metrics. This excessive risk

is reflected in a greater loss than what UHF’s portfolio endured in 2008 and 2009. See

Table 9 - UHF FY 2008, 2009 & 2012 Performance Relative Indices. Ultimately, for the

time period evaluated (July 1

st

, 2003 to June 30

th

, 2012), the Swensen portfolio produced

superior returns for the volatility – as judged by the Sharpe and Sortino Ratios.

20

Academic fiscal years run from July 1

st

to June 30

th

of the following year. For example, fiscal

year 2012, (FY2012), runs from July 1

st

2011 through June 30

th

, 2012.

21

One fund, State Street Global Advisors S&P 500 Index, underperformed a comparable

Vanguard Index by the exact difference of their expense ratio.

22

As calculated by computing the average years a fund is held, over the 8 years that the holdings

were documented in UHF’s annual endowment reports.

US Equity

19%

International

Developed

16%

Emerging

8%

Fixed Income

13%

Cash Equivelants

4%

Marketable

Alternative Assets

19%

Private

Equity/Venture

Capital

6%

Inflation Hedge

Assets

15%

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 31

Performance Metrics of Nine Consecutive FYs, ending June 30th, 2012

Portfolio

Annualized

Returns

Total

Return

STD

Dev.

Sharpe Ratio

Sortino

Ratio

UHF actual

6.37%

74.30%

11.7%

0.414

0.248

S&P 500

5.91%

67.71%

17.5%

0.290

0.193

60/40

5.88%

67.28%

9.8%

0.406

0.194

Swensen 65/30/5

8.86%

114.63%

13.6%

0.540

0.531

Table 8 - Performance Metrics of Nine Consecutive FYs, ending June 30th, 2012

UHF FY 2008, 2009 & 2012 Performance Relative Indices

Portfolio / Index

FY 2008

FY 2009

FY 2012

UHF actual

-1.7%

-16.8%

-2.1%

S&P 500

-13.12%

-26.22%

5.45%

60/40

-4.00%

-13.08%

6.60%

Swensen 65/30/5

-2.93%

-20.37%

7.34%

Table 9 - UHF FY 2008, 2009 & 2012 Performance Relative Indices

Figure 6 - University of Hawaii Foundation & comparison portfolio growth

Conclusion

In the case of UHF and the data analyzed thus far, it would appear that active

management and the accompanying alternative assets are effectively minimizing

portfolio losses in certain instances – buffering the portfolio from the sub-prime

crisis. UHF’s active management and alternative asset allocation thus acted as a slight

hedge against sharp market downward movements, making the portfolio more buoyant

than the comparison portfolio.

23

23

More risk for more return – this is a tenet of modern portfolio theory as discussed in the

literature review. The ability to buffer against the sub-prime crisis has come at the expense of

1.03

1.23

1.43

1.63

1.83

2.03

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

Growth of Wealth Factor

UHF Actual

S&P 500

60/40

Swensen 65/30/5

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 32

For all its active management and alternative assets, UHF’s portfolio manager has

sometimes managed to reduce negative returns amidst markets shocks. UHF’s portfolio

outperformed in FY 2008 and 2009, but produced exceptionally poor performance in FY

2012. FY 2012 performance is the basis for the hypothesis’s rejection.

UHF Portfolio Performance Discrepancies Relative Index-Based Portfolios

Portfolio / Index

Return

STD

Sharpe

Sortino

FY 2008

FY 2009

FY 2012

S & P 500

0.46%

-5.80%

0.12

0.06

11.42%

9.42%

-7.55%

60/40

0.49%

1.90%

0.01

0.05

2.30%

-3.72%

-8.70%

Swensen

-2.49%

-1.90%

-0.13

-0.28

1.23%

3.57%

-9.44%

Key

UHF Superior Performance

UHF Inferior Performance

Table 10 - UHF Portfolio Performance Discrepancies Relative Index-Based Portfolios

returns. The same benefit, it be argued, could be had with a less aggressive equity allocation. This

idea – that an index-based portfolio with a greater allocation than 30% to fixed income could

outperform UHF’s portfolio – is discussed in the conclusion. Those readers eager to see the

results may skip to University of Hawaii Foundation on page 51.

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 33

Washington State University Foundation’s Endowment Fund

Washington State University Foundation’s Endowment Fund (WSUFEF) holds $318.1

million as of June 30, 2012.

Figure 7 - Washington State University Foundation’s Endowment Fund asset allocation

It posted a 6.16% per annum return over the last 10 FYs. WSUFEF’s performance in

times of market crisis was mixed. For FY 2008, when the first effects of the sub-prime

crisis were being felt, WSUFEF pushed out a small positive return of 1.6%. This is in

contrast to the S&P, which fell in excess of 13%. However in 2009, WSUFEF fell

dramatically with the market.

Performance for 10 FY Returns, ending June 30th, 2012

Portfolio / Index

Annualized

Returns

Total Return

STD Dev.

Sharpe

Ratio

Sortino

Ratio

WSUFEF actual

6.16%

130.77%

12.16%

0.40

0.217

S&P 500

5.33%

106.98%

16.68%

0.27

0.140

60/40

5.76%

119.11%

9.25%

0.42

0.179

Swensen 65/30/5

8.56%

215.62%

12.87%

0.55

0.514

Table 11 - Performance for 10 FY Returns, ending June 30th, 2012

WSUFEF FY 2003, 2008, 2009 & 2012 Performance

Portfolio / Index

FY 2003

FY 2008

FY 2009

FY 2012

WSUFEF actual

2.63%

1.60%

-21.10%

0.00%

S&P 500

0.26%

-13.12%

-26.22%

5.45%

60/40

4.68%

-4.00%

-13.08%

6.60%

Swensen 65/30/5

5.89%

-2.93%

-20.37%

7.34%

Table 12 - FY 2003, 2008, 2009 & 2012 Performance

Figure 8 - Washington State University Foundation’s Endowment Fund & comparison

portfolio growth shows the value added by active management and alternative asset

allocation: greater stability in returns. Again, active management and alternative assets

are behaving like fixed-income: stifling returns in exchange for safety of principal.

U.S. Equity

14%

Non-U.S. Equity

17%

U.S. Fixed Income &

Cash

13%

Absolute Return

20%

Real Estate

15%

Private Equity

21%

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 34

Figure 8 - Washington State University Foundation’s Endowment Fund & comparison portfolio growth

Swensen Portfolio

The Swensen portfolio grossly outperformed the WSUFEF portfolio in excess of 2% per

annum. The trade-off, as seen in the previous case study, was an increase in volatility,

albeit a small one (less than one percent of standard deviation). The Sharpe and Sortino

Ratios, laid out in Table 11 - Performance for 10 FY Returns, ending June 30th, 2012

manifest the value added of the Swensen model over WSUFEF via higher scorings.

Further, the Swensen model outperformed in three out of four ‘bad years.’

Conclusion

The verdict of WSUFEF is similar to University of Hawaii Foundation (UHF). While

WSUFEF’s portfolio forfeited performance to gain safety, ultimately poor FY 2012

performance precluded the acceptance of the hypothesis. Actively managed alternative

assets undoubtedly added value, functioning to buffer WSUFEF’s portfolio, most

substantially at the start of the financial crisis (FY 2008). However, in exchange for

slightly less volatility and a better 2008 return, the WSUFEF portfolio gives up every

other metric to Swensen, including returns in excess of 2% per annum over 10 years.

WSUFEF Portfolio Performance Discrepancies

Portfolio / Index

Return

STD

Sharpe

Sortino

FY

2003

FY

2008

FY

2009

FY

2012

S & P 500

0.82%

-4.52%

0.13

0.08

2.37%

14.72%

5.12%

-5.45%

60/40

0.39%

2.91%

-0.02

0.04

-2.05%

5.60%

-8.02%

-6.60%

Swensen 65/30/5

-2.40%

-0.71%

-0.15

-0.30

-3.26%

4.53%

-0.73%

-7.34%

Key

WSUFEF Superior Performance

WSUFEF Inferior Performance

Table 13 - WSUFEF Portfolio Performance Discrepancies

1.00

1.20

1.40

1.60

1.80

2.00

2.20

2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

Wealth Growth Factor

WSUF

S&P 500

60/40

Swensen 65/30/5

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 35

University of Northern Carolina, Wilmington

At the conclusion of FY 2012, the University of Northern Carolina, Wilmington

(UNCW) had nearly $68 million AUM. The university privately provided 11 years of

investment return data for this study.

Figure 9 - University of Northern Carolina, Wilmington asset allocation

Swensen Portfolio

The Swensen portfolio again outperforms the case study portfolio UNCW, posting

returns in excess of one percent per annum. This gain in returns is offset by additional

volatility. Like UHF, UNCW’s portfolio exhibited superior sub-prime crisis performance

(FY 2008 & 2009).

UNCW Performance of 11 Consecutive FYs, ending June 30th, 2012

Portfolio / Index

Annualized

Returns

Total

Return

STD Dev.

Sharpe

Ratio

Sortino

Ratio

UNCW actual

6.77%

105.54%

10.72%

0.49

0.33

S&P 500

2.96%

37.89%

17.48%

0.13

-0.05

60/40

4.51%

62.39%

9.66%

0.28

-0.01

Swensen 65/30/5

7.81%

128.79%

12.49%

0.50

0.44

Table 14 - UNCW Performance of 11 Consecutive FYs, ending June 30th, 2012

U.S. Equity

24%

Non-U.S. Equity

10%

Global Equity

17%

U.S. Fixed Income

32%

Energy & Natural

Resources

4%

Real Estate

1%

Private Equity

9%

Commodities

1%

UNCW FY 2002, 2003, 2008, 2009 & 2012 Performance

Portfolio / Index

FY 2002

FY 2003

FY 2008

FY 2009

FY 2012

UNCW actual

-6.93%

1.90%

4.99%

-14.48%

5.70%

S&P 500

-17.99%

0.26%

-13.12%

-26.22%

5.45%

60/40

-7.27%

4.68%

-4.00%

-13.08%

6.60%

Swensen 65/30/5

0.67%

5.89%

-2.93%

-20.37%

7.34%

Table 15 - - UNCW FY 2002, 2003, 2008, 2009 & 2012 Performance

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 36

For the risk endured, the Swensen model outperformed, posting superior risk-adjusted

returns. While the difference in Sharpe Ratio was negligible, the difference in Sortino

Ratios was notable. (See Table 14 - UNCW Performance of 11 Consecutive FYs, ending

June 30th, 2012.) And while the UNCW portfolio proved more resilient to the recent

subprime crisis (FY 2008 & 2009) than the Swensen model, the Swensen model posted

better returns in the wake of tech bubble (FY 2002 & 2003).

Figure 10 – University of Northern Carolina, Wilmington & comparison portfolio growth

Conclusion

The hypothesis is again rejected. While the UNCW portfolio did underperform the

Swensen model with less risk, it did not post superior performance in every instance of

the ‘bad years.’ See the following Table 16 - UNCW Portfolio Performance

Discrepancies.

Table 16 - UNCW Portfolio Performance Discrepancies

0.80

1.00

1.20

1.40

1.60

1.80

2.00

2.20

2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

Wealth Growth Factor

UNCW

S&P 500

60/40

Swensen 65/30/5

UNCW Portfolio Performance Discrepancies

Index

Return

STD

Dev.

Sharpe

Sortino

FY

2002

FY

2003

FY

2008

FY

2009

FY

2012

S & P 500

3.81%

-6.76%

0.36

0.38

11.06%

1.64%

18.11%

11.74%

0.25%

60/40

2.26%

1.06%

0.21

0.34

0.34%

-2.78%

8.99%

-1.40%

-0.90%

Swensen

-1.04%

-1.77%

-0.01

-0.11

-7.60%

-3.99%

7.92%

5.89%

-1.64%

Key

UNCW Superior Performance

UNCW Inferior Performance

Jon Luskin - MBA Thesis v4.docx Page 37

University of California, Santa Barbara Foundation

University of California, Santa Barbara Foundation (UCSBF), reported $206,033,000

AUM at the end of FY 2012.

Figure 11 - University of California, Santa Barbara Foundation asset allocation

Among its fellow UC foundations, UCSBF posted the worst returns for the 14 year

period evaluated: 4.22% per annum. UCSBF’s performance is reflected in a negative

Sortino Ratio. It is the only portfolio to generate a negative Sortino Ratio in this study.

UCSBF Fourteen FY Returns, ending June 30th, 2012

Portfolio / Index

Annualized

Returns

Total

Return

STD Dev.

Sharpe

Ratio

Sortino

Ratio

UCSBF actual

4.22%

78.42%

12.64%

0.17

-0.003

S&P 500

3.16%

54.62%

17.03%

0.10

-0.038

60/40